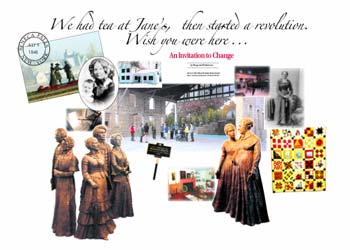

We had tea at Jane’s, then started a revolution. Wish you were

here.

An Invitation to Change

By Margaret Michniewicz

Imagine

yourself leading the charge for social improvement! In less time than

it takes for us to get to Washington DC or even Philadelphia, I went with

a group of Vermont women to Seneca Falls, NY, to see what women like Elizabeth

Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott have done. Vermont’s motto, "Freedom

and Unity," is right in line with the ideals that flourished in Seneca

Falls 150 years ago, as progressive women championed basic human rights

that were still denied over half the population under the Constitution.

A pilgrimage to Philly or DC is to pay homage to a country whose work

was only half done. Seneca Falls is the monument to all the truths that

are self-evident. Imagine

yourself leading the charge for social improvement! In less time than

it takes for us to get to Washington DC or even Philadelphia, I went with

a group of Vermont women to Seneca Falls, NY, to see what women like Elizabeth

Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott have done. Vermont’s motto, "Freedom

and Unity," is right in line with the ideals that flourished in Seneca

Falls 150 years ago, as progressive women championed basic human rights

that were still denied over half the population under the Constitution.

A pilgrimage to Philly or DC is to pay homage to a country whose work

was only half done. Seneca Falls is the monument to all the truths that

are self-evident.

The flavor of America in 1848 was comparable to that of the 1960’s

– an era of civil rights, women’s rights, social reforms,

monarchies toppled around the world, even a bit of free love and communal

living – and the flashpoint on the globe was a small mill town to

our west, the size of Bellows Falls. Nowhere on earth could women vote;

the community of Seneca Falls would become the epicenter of a massive

civil rights quake.

Mother of Necessity

"Why did it happen here?" we kept wondering, and were offered

the interesting history about the impact of the Erie Canal and railroad

on Seneca Falls as a hub of westward travel; the exchange of ideas via

touring speakers and the abolitionist press; and the profound egalitarian

influence of the Quakers. All these complex layers were influential, and

fascinating in and of themselves. But above all – Seneca Falls was

where Elizabeth Cady Stanton lived.

A baby named Elizabeth Cady was born in 1815 in Johnstown, NY; a woman

named Elizabeth Cady Stanton was born in Seneca Falls. There, in a tiny

house on Washington Street bringing up her seven children – the

self-described "caged lioness" paced, her mind too active to

be contained within those clapboard walls. She was thirty-two years old.

Having met some friends for tea, Cady Stanton later recalled: "I

poured out the torrent of my long-accumulating discontent, with such vehemence

and indignation that I stirred myself as well as the rest of the party

to do and dare anything." She incited the four other women, all of

whom were Quakers, to put out the call for a convention: and with just

10 days notice, 300 people traveled to attend the first Women’s

Rights Convention in American history. No phones, no Internet. That’s

networking.

An Activist is Born

In 1840, at the age of 24, Elizabeth Cady Stanton went to London on her

honeymoon, planning to attend the International Anti-Slavery Convention

with her husband. She watched as 500 abolitionists wasted a day arguing

over the role of women, finally deciding that the eight women attending

the convention would be segregated, and not allowed to speak.

Not allowed to speak!

The lioness spent the next eight years back in Seneca Falls tending her

children and her house – until the day in July, 1848, at Jane Hunt’s

house when she symbolically put down her teacup, threw back her head,

and roared. It was a roar of indignation toward injustice that would last

until her death in 1902 – a roar of eloquence, passion, and wit.

What were they calling for at that convention in 1848? Rights so basic

you may wonder what the big deal is with the Declaration of Sentiments.

But the convention was nearly split apart by Cady Stanton’s insistence

that they call for the right to vote. Even Lucretia Mott balked: "Lizzie,

you’re going too far." Frederick Douglass, the great orator

and women’s rights ally, spoke eloquently at the gathering, and

convinced them of what he knew for himself as an African-American –

without the vote, it’s not possible to change the laws that treat

you unfairly.

"The right is ours," Cady Stanton insisted. "Have it we

must. Use it we will." This was, incidentally, her first time ever

speaking to a public gathering. In the end, 68 women and 32 men signed

the Declaration of Sentiments. The Revolution had begun.

Get There From Here

It’s far more interesting to travel via secondary roads, but don’t

do it if you’re on limited time. Jump on the Thruway, past signs

for the Baseball Hall of Fame, and the Boxing Hall of Fame. If you’re

lucky, you too will have passengers who break out into the "Suffragette

Song" from Mary Poppins. Watch for Exit 41: Women’s Rights

National Historical Park (WRNHP), Seneca Falls. That’s right. Not

just the Hall of Fame but an entire National Park.

In content, the WRNHP shares the magnitude of other national parks, yet

it’s comfortably cozy. Much of the park is within walking distance

on a classic turn-of-the-century main street (touted proudly among locals

as Capra’s inspiration for "It’s a Wonderful Life").

There’s a lovely, lamp-lighted walkway to a gazebo near the riverfront,

which has now become the site of an annual women’s music festival

(see Women on the Rise, page 15). Allow ample touring time — park

officials cautioned us that people are always coming with the idea that

they can ‘do’ Seneca Falls in two or three hours, and regret

having to leave too soon.

Welcome to the Revolution

Greeting you at the Visitors’ Center of the Park are twenty life-size

bronze statues of feminism’s First Wave giants: Elizabeth Cady Stanton,

Lucretia Mott, Frederick Douglass… along with eleven anonymous figures.

These eleven represent those who attended the 1848 Convention but whose

names are not recorded. It’s an important reminder to us that history

is not made by those who are already famous… it could be you.

Going to the Chapel

Nestled along the side of the Visitors’ Center is the Waterwall,

symbolizing the original Seneca Falls, and inscribed with the 1848 Declaration

of Sentiments and the names of the 100 men and women who signed. From

here, overlooking Declaration Park, is the "Independence Hall"

of Seneca Falls, the Wesleyan Chapel. This architectural artifact of the

1848 convention was subject to later disfigurement as a car dealership

and laundromat, altered beyond recognition and with no surviving documentation

of how the original structure looked. In a competition sponsored by the

National Endowment for the Arts, two women collaborated to present the

winning design for the restoration of the Chapel site. The design removed

the non-historic façade from the Chapel, and exposed the original

structural elements of the building. No longer enclosed by four walls,

the Chapel now has the magnificence of an open-air temple. It’s

a lovely monument to those who convened for our rights, and then dispersed

to spread the message.

The park rangers assured us it is a lovely reflecting spot in the summer,

with the Waterwall running parallel. Our February visit was highlighted

by the full moon, so the site was monumental even at night, even in the

dead of winter. So go now and reflect quietly, or join in the joyous reenactments

during Convention Days of July, or when the leaves begin to fall from

Cady Stanton’s horse-chestnut tree.

Along the Underground Railroad

Elizabeth Cady Stanton regularly made the 15-mile trip to nearby Auburn

to visit at the homes of women’s rights allies including Abraham

Lincoln’s Secretary of State, Governor William H. Seward. The Seward

Home is a collection of the family’s fine art and extravagant home

furnishings, and relics of this statesman’s long public career and

worldwide travels. Did you know that on the night Lincoln was shot, attempts

were also made on the lives of his Vice President and Secretary of State?

On display are remnants of the blood-stained sheet from Seward’s

stab wounds when he was attacked in bed at his Washington home. Or, you

can savor the preserved piece of the Duke of Windsor’s wedding cake.

A long list of distinguished historic figures visited this Auburn home,

including Ulysses S. Grant, John Quincy Adams, and William McKinley. It’s

poignant to imagine the leader his daughter might have become —

in a letter written to her father about the Fugitive Slave Act, the 14-year-old

girl beseeched him to stop "those stealers of men." Sadly, she

died at age 21. Concealed beneath the magnificent opulence of Seward’s

mansion there are more surprises. He had set up fully furnished underground

living quarters as a stop on the Underground Railroad. William Seward

did honor to our Democratic Republic. His door was as open to the government’s

chief executive as to those escaping enslavement.

Half a mile down the street from the Seward Home are the grave and the

homesite of the indomitable Harriet Tubman. It was because of Seward that

Tubman settled in Auburn after her own escape from slavery. Tubman purchased

her two-story home from Seward, refusing his charity; he was breaking

the law by transferring property to her. "Settled" may not be

an appropriate term: at great peril to herself, Tubman made 19 trips back

to the South and guided over 300 men, women, and children out of forced

labor in the slave states. Tubman eventually purchased 26 acres around

her home, which are still intact. The grounds include a museum honoring

the Underground Railroad itself. Lest the real history of this country

become too abstract, it’s worth reflecting on the iron leg shackles

on display – a reminder of what Tubman was rescuing people from.

So necessarily secret was the Underground Railroad that much is not known

even today. A highlight of the Tubman site was a quilt, commissioned recently

for the museum. In addition to images of this modern era "Moses"

and her church, it is a composite of the many symbols that were hung outside

houses along the route north as guiding clues to refugees from slavery.

A wagon wheel, for example, signaled travelers to take only as much as

they could carry in a sack or a small wagon. A bear’s paw directed

them to follow bear or deer tracks to find water or cross mountains. The

Bowtie pattern meant that someone would meet you with new clothes. The

Drunkard’s Path was a warning to travel in a zig-zag pattern to

evade trackers. The Tumbling Blocks meant pack up and move on!

Simply reaching the North did not ensure fugitives’ safety. Elizabeth

Cady Stanton’s husband was an agent for the Anti-Slavery Society,

and survived 200 angry mobs in every northern state from Maine to Indiana

– with the notable exception of Vermont, which he said alone "abstained

from that fascinating recreation."

Come Stand Among Great Women

Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Harriet Tubman are among the 207 currently

inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame (see Steen, page

#). There are many more great women present here – not all of whom

are household names. It was striking to reflect on those defiant spirits

who were the firsts of their gender, such as Amelia Earhart, Sally Ride,

and many more. What was perhaps even more powerful was being surrounded,

in effect, by dozens of women who were the firsts people in any of their

domains – so often these accomplishments led to the betterment of

the world and the human condition.

It is this connection to the rest of the world, and the efforts by individuals

at the local level to push for righteous change that is what makes Seneca

Falls an inspirational and important place to experience. Our own Vermont

Woman excursion was brought to a spiritual full circle during our final

stop on our all-too-brief visit. The Center for the Voices of Humanity

is the cultural center, gallery, and library of an international organization:

IDEA – the International Association for Integration, Dignity and

Economic Advancement. Of all the places in the world where the Center

might have been located, Seneca Falls was specifically chosen because

of its 150-year tradition of individuals advocating for universal human

rights. The organization itself was originally founded for, and mainly

by, those who’ve experienced Hansen’s Disease, to challenge

the erroneous stigmatisms of leprosy. The gallery of the Center features

beautifully displayed, large-scale photographs, arts, poetry, and quotes

from people around the globe. A breathtaking photographic exhibit of the

lotus flower in various stages of life was punctuated by the quote "Never

Believe We are Powerless." The mission of the Center emphasizes that

"although you cannot always control what happens in life, you can

always control how you will respond."

Throw a Tea Party

The iconic image of America’s revolution was the Tea Party in Boston

– dramatic and overt in character. A continuation of the revolt

was necessary, from the tyranny of gender and racial oppression. This

second, more covert revolution – emanating from Seneca Falls, New

York – was ignited during an everyday domestic ritual by courageous

and determined women who could no longer be content to simply sip tea

when there were injustices in the world and work to be done to make the

lives of others safer and happier.

It was time for "all our young ladies to come forth and boldly declare

themselves on the side of reform… " Cady Stanton wrote in reflection.

"Then arises the question how are we to accomplish the end desired…

If we say we love the cause and then sit down at our ease, surely do our

actions speak the lie."

May I pour you a cup?

photos: Chris Bretschneider, Katie Decker and courtesy of Seneca County

Tourism National Women’s Hall of Fame

IT IS OUR MISSION

. . . To Honor in Perpetuity those Women,

citizens of the United States of America,

whose contributions to the arts, athletics,

business, education, government,

humanities, philanthropy, or science

have been of the greatest value

for the development of their country.

For useful links and resources related to this article click

here!

|