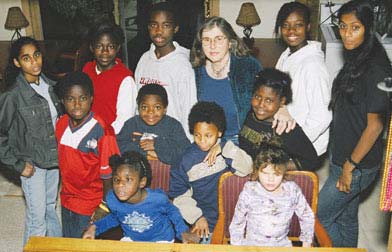

Theresa Tomasi: Still an Angel Two Decades LaterPhotos By Margaret Michniewicz

When you first hear of Theresa Tomasi, she seems more like a character in a nursery rhyme or a folktale than a real person. A mother of twenty-three children? But she’s not the old woman who lived in a shoe. She knows what to do. Tomasi adopted her first child, Tracy, in 1962 in Canada after having been repeatedly rejected as an adoptive mother in the U.S. because she was single. In Montreal, her marital status was considered an obstacle but not a complete barrier. On the other hand, religion became an issue; the “hard to place” child she wanted was refused her because Quebec law prohibited adoption across religious lines: the child was Protestant, Tomasi Catholic. Finally, a friend connected her with the Catholic Welfare Bureau. Her social worker struggled with the unorthodoxy of her singleness, but after much wrangling, Tomasi succeeded in bringing one-year-old Tracy home to Vermont. Forty-plus years later, she’s still at it. Tomasi's children have come from Ecuador, India, Cambodia, Bangladesh, Canada and the U.S. The North American children reflect combinations of Jewish, Catholic, Protestant, black, white, and Native American ancestry. Those living with her now come from India (two), Ghana (five siblings plus one) and the U.S. (four). But why did she want to adopt a child in the first place? “I was thirty-two when I broke up with this guy and went to McGill to graduate school,” she explained. But she’d always wanted children. Like many single women, she thought, “Why couldn’t I just have children and not have a husband?” In the beginning, Tomasi had no plans for a large family. “I adopted one and it seemed great. Then I adopted the second and it seemed great. I just kept doing it.” Tomasi is a bright, active, strong-willed woman. She has long, thick, graying wavy hair, a slim build, and an easy laugh. She gives the impression of being comfortable in her body and in her world. Trained as a social worker, she spent many years as Director of Social Work at what is now called Fletcher Allen (formerly MCHV). Her home in Williston consists of a large farmhouse on fifty acres at the end of an otherwise suburban-feeling street. The long dirt driveway seems fairly typical. But the first thing you see when you enter the house is about forty or fifty small shoes lined up in neat little rows, ten or twelve pairs to a row, with a few haphazard stragglers around the edges. The coat rack looks like someone’s having a party, with coats piled a foot high on top of each other. There are three large animal crates—one for the dog, True; one to feed the cat that’s not housebroken; and one to contain a litter of tiny Siamese kittens. And yet it doesn’t feel crowded. Here and in the rest of the house, the feeling is not one of chaotic pressure, but of abundance. The living room overflows with overstuffed furniture and pillows; artwork covers the walls; photographs and books spill across surfaces. In addition to plenty of comfortable, richly textured places to sit and sprawl, there’s plenty of bare table space for doing homework. Twelve children live with Tomasi now, and yet there is a feeling of order and space, both physical and emotional. In Tomasi’s bedroom, stuffed animals line one wall of the large room. An extra, double-bed-size futon on the floor is lumpy with comforters and pillows. Who sleeps here? I ask. “Anyone who wants to.” There’s always a place in Mom’s room if you have a bad dream—or a bad week. There is no “poverty mentality” here, of the kind that restricts people’s generosity. How has she done it? How does she manage all these children—and for that matter, all these objects (because we all know that keeping order involves constantly moving objects from one place to another)? “The kids help out,” she says simply. Nineteen years ago when I first interviewed Tomasi, I took this same statement at face value: Of course; they would have to. But now, having seen a lot more families struggle to raise good kids, I wonder, yes, but how do you create such a harmonious environment where the kids naturally help out? Tomasi is nothing if not well organized. Every night before the kids go to sleep, they show her what they’re going to wear the next day. Every day after school, they come home, change clothes, work on homework for an hour, and do their chores, and then they’re free to go off and play. Sounds simple enough. This is how this plays out in real life: a group of children burst in the house with an explosion of kid-energy; they wander in to greet the guest politely; the parrots, excited by the increase in energy go berserk with their squawking (which Tomasi says she doesn’t notice); a younger child crawls into her lap for a snuggle; most of the kids retreat to their rooms to change clothes; an older child prods a younger one to get going; another older child takes over the care of a blind sibling. It’s all very noisy and companionable and without incident. It works. Tomasi acknowledges that it works a lot more smoothly now that she has retired and is able to stay home. She left the hospital after 28 years, and then ran the Lund home for another five, until 1996. “I hated to give up being employed, but it’s very hard to be a working mother.” This particular dilemma hasn’t changed in the past two decades. “It’s always a stressor, how to balance things,” she concedes. At one point, Tomasi had help from her mother, who lived with her for two years. Later her mother developed Alzheimer’s disease and needed to be cared for elsewhere; Theresa and her now-19-year-old daughter, Toria, visited Tomasi’s mother every day until she died in 1997. Tomasi calls Toria a gifted caregiver. The household’s older children have always helped with their younger siblings, but Tomasi says she couldn’t care for her two more demanding children—one blind, the other with multiple challenges—without Toria’s help. How does she manage twelve children logistically? Last year all but two of the younger kids went to the Brownell Mountain School. This year most attend Williston Central or Allenbrook (part of Williston’s public school system). Tova attends Rice High School, Talia attends Central Vermont Academy (and lives with Torah, a pediatrician, and her husband, Neil, in Montpelier during the week), and two study at home. Toni, now grown and living in Colchester, drives Tova and a neighboring child to Rice in the morning, on her way to work as an adoption assistant at the Lund Home; a neighbor brings the two children home. But what about their after-school activities? How does she keep track of it all? “My kids have to take responsibility for what they’re doing. I do keep very close track of them. But my kids don’t run hither and yon.” However, the kids living with her now do a lot more individual activities than her older children used to do. Tomasi notes that while she worked at the hospital, “We did things as a family. It’s hard to keep track when you’re at work. The older kids might feel they lost out.” Nowadays, almost all her kids play soccer. How does she handle the logistics? “There’s no secret. You just have to coordinate. I do a lot of running around, but people have been very generous. I used to feel I should do it all, but—” She laughs at herself and doesn’t finish: surely the futility of such a position is obvious. She described running out in the middle of dinner to pick kids up, always having to leave others at home. Now other adults help carpool. “People are really kind,” she repeats. But kindness and emotional support don’t pay the bills. How in the world has she managed financially? Tomasi lives on social security and retirement income; she took the buyout from MCHV. Some of her adoptions have involved a certain amount of expense, she acknowledges, but on the other hand, a couple have been subsidized adoptions. “Instead of paying foster care for the rest of the child’s life,” she explains, “the state helps support their adoption. I don’t know what we’d do otherwise. We’re blessed.” While she was working, her kids were covered through her health insurance. She tried to find insurance after her benefits ran out. “But nobody would cover a family our size. [And] they laughed about dental.” Since then, her children have received health and dental care through Dr. Dynosaur, Vermont’s state-sponsored insurance plan for children needing assistance. It helped that as a social worker she knew the systems. It also helped to know something about child development and the issues some adopted children face. “For example, kids who have had multiple placements may have trouble bonding.” On the other hand, as with any parent struggling with a child, “that knowledge doesn’t always carry you through the difficulty.” How has her family worked for the kids? “Are things always happy? No. People don’t always come together easily. But they get along. But that’s just a style. Then there’s how do you really interact and support each other? My kids are very tuned into each other.” Some of her children have been traditionally successful in school, and others have struggled. Among the adults, all seem to be finding their way. In addition to Torah and Toni mentioned above, Tracy, a singer, runs the Good Times Café in Hinesburg with her husband, Chris. Thomas is a carpenter/builder in Williston. Timothy works with cars in Richford, Troy waits tables in California, and Tristan is in the navy. Taylor does road work in Vermont. Tai, who is blind, has just begun graduate school in Utah. “I don’t have an answer. Every single child is an individual. They’ll take their potential and do what they want. Sometimes they don’t and you’re disappointed. But I look at myself: have I lived up to my potential? Does anyone?” She laughs. Like all families, Tomasi’s has had its share of sadness. Toby died in an accident with a train just after Christmas in 1991, two months shy of his eighteenth birthday. “He was a really kind human being,” Tomasi says. “Everyone loved him.” Mira, “the dearest person,” came to the U.S. with a heart problem and died in the hospital. Tomasi enjoys telling stories of Mira’s wisdom. One day Mira asked, “Why does everyone in America bring you things when they visit you in the hospital?” Tomasi explained that it was their way of showing they liked her and wanted her to get well. “Why can’t they just say it in words?” the girl asked. Tomasi notes that some people have looked critically upon her multiple adoptions. “They say, ‘Why would you want so many,’ implying that I have enough. But I’ve got news for them. There are plenty of children needing homes in Africa and India. We’ve got our heads in the sand. These children live in such hardship. They don’t have running water or refrigeration; it’s never under ninety degrees. They have no paper or pencils, although they have good teachers. And there are plenty of children in the U.S. needing homes—just waiting, because they’re of a different ethnic group or have medical challenges, or are older or part of sibling groups.” Single adoptions are no longer an issue. Adoption in general reflects society’s evolution, notes Tomasi. Gay, single, partnered adoptions are all possible, at least in Vermont. This fall, Tomasi was named an Angel of Adoption by the Congressional Coalition on Adoption Institute. She is grateful, but quick to dispel any illusions about being angelic. “I do it because I enjoy it. I’m not terribly social, I don’t like to go to parties. Being a mother in this way falls in with my interests and desires. There’s nothing that makes me happier than adopting another child.” Suzi Wizowaty is the author of The Round Barn (a novel for adults) and a forthcoming novel for children, A Tour of Evil. She teaches writing at St. Michael's College. She first interviewed Theresa Tomasi for Vermont Woman in December, 1985

|