No Longer a Need to Suffer in Silence:

Treating Incontinence & Pelvic Floor Disorders

By Roberta Nubile

Ellen's (not her real name) story began with the birth of her first child. During the prolonged pushing stage of the delivery of her nine-pound-plus child, she was given an episiotomy, or surgical enlargement of the vulval orifice, without her expressed consent or knowledge. The procedure caused a third-degree tear extending from the episiotomy into the rectal muscle. After the birth, she experienced frequent bowel incontinence and occasional urinary incontinence.

At her follow up OB/GYN appointment, Ellen asked about the incontinence and was told to "give it time." Months later, without improvement, she again appealed to her OB/GYN and was referred to a highly recommended Vermont proctologist, who advised her to eat more fiber, cautioned her against further vaginal births, and told her that Kegel's exercises, the squeezing and releasing of the pelvic floor muscles, were of little value, as this was not a muscular problem. Ellen assumed there was little hope for recovery, and says she "didn't know what to do, other than not get pregnant again."

Ellen lived with bowel incontinence for two years, and then discovered she was pregnant again. She chose to deliver at a different hospital, and assembled a support team to ensure that she would have a voice this time to refuse an episiotomy.

During the pregnancy, the bowel incontinence subsided, but she was keenly aware of the risk of a prolapsed uterus, which is a uterus that has moved from its normal position in the abdominal cavity, usually into a lower position, and can cause problems during pregnancy. Ellen did up to 300 Kegels a day. She lived in fear of being put on bed rest, needing a Caesarean birth, or needing corrective surgery post-birth-or all three. She also tried Mayan abdominal massage, herbs to support the uterus, and a belly band, all in the hopes of decreasing the downward pressure on her pelvic muscles.

Online research led her to several discoveries. First, that episiotomy with a third- or fourth-degree tear is a risk factor in weakened pelvic-floor musculature. Second, that the rectal incontinence she was having came under a clinical diagnosis of pelvic floor disorders. And third, treatment for pelvic floor disorders was best done by a urogynecologist, not a proctologist. She wondered why she had not been advised about any of those findings by her doctors.

After a successful, uncomplicated vaginal birth (without an episiotomy), she contacted Drs. Anne Viselli and Diane Charland at their practice in South Burlington, Vermont Urogynecology. They started her on physical therapy for pelvic floor retraining. Her eleven visits were paid for by her insurance company. The treatments included Kegel's exercises, breaking down scar tissue from the episiotomy, and retraining muscle groups.

Ellen is thrilled with the outcome. She avoided surgery and, after living with fecal incontinence for three years, has not had any recurrence since treatment.

"There is a lack of education - even among providers - in the many options for women with urinary incontinence and other pelvic floor disorders," says Dr. Viselli.

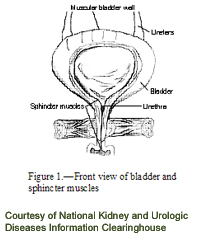

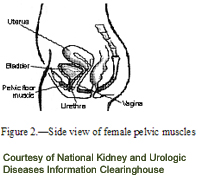

The pelvic floor is a network of muscles, ligaments, and tissues that act like a hammock to support the organs of the pelvis: uterus, bladder, and rectum. Pelvic floor dysfunction is the overarching term for a group of conditions that includes urinary incontinence, anal incontinence, bladder and uterine prolapse, and other sensory and emptying abnormalities of the urologic and gynecological organs.

Risk factors for pelvic floor disorders in women include pregnancy and childbirth, forceps delivery, episiotomy accompanied by a large tear, chronic pressure on the pelvic organs (e.g. with constipation, coughing, or lifting), genetics, sexual trauma, and surgery involving pelvic floor muscles. Female clients with pelvic floor disorders may be of any age, but the majority tend to be in their thirties to their sixties.

Statistics vary on the occurrence of urinary incontinence and pelvic floor disorders in women. This may be due in part to underreporting, caused by privacy and social isolation issues associated with the conditions, as well as differing definitions of incontinence from woman to woman. Some may feel that it is a normal part of aging to have some loss of pelvic floor muscle function, and learn to live with it without complaint. What many don't know is that there is much room for improvement with appropriate treatment, and one doesn't need to live with the incontinence or pain.

Pelvic floor disorders can cause severe loss of quality-of-life. A woman with urinary incontinence may need to map out her day according to where the bathrooms are or may have to limit fluid intake. She may avoid sports and exercise for fear of losing urine or stool, and thus gain weight, starting a vicious cycle. Sexual intercourse may become limited to avoid embarrassment or in some cases, pain. Some women feel they can't leave the house at all, since spontaneous laughing, sneezing or coughing can produce incontinence of urine or stool.

The goal of treatment, according to Dr. Viselli, is to return women to a satisfactory quality of life. The type of treatment depends on the kind of bladder, uterine or rectal problem the patient has, how serious it is, and what best fits her lifestyle. Non-invasive treatments include education about the pelvic floor anatomy, biofeedback, Kegel's exercise, behavioral therapy, medications, pessaries, implants and muscle retraining. Surgery is a viable option when quality of life has not been restored by the non-invasive methods.

Fortunately, Vermont's providers - physicians, physical therapists, and naturopathic doctors - are well-versed in these treatments. The challenge is getting women to seek treatment in the first place.

"Many women will go on for years before seeking help with urinary incontinence - they are embarrassed and feel alone," says Dr. Julie Lacombe, assistant professor in OB/GYN at the University of Vermont.

A 2004 survey done by the National Association for Continence showed that women live with their symptoms for an average of six and a half years before seeking treatment; men wait an average of about four years.

"It's really 'mind over bladder'," Dr. Lacombe continues. "It is often a matter of retraining muscles, often through something called biofeedback." Biofeedback helps a woman to "see," via waveforms on the computer, the strength of her pelvic floor muscle squeezing, thus allowing her to set measurable goals and chart her progress.

Jane Kaufman, of Phoenix Physical Therapy, with offices in South Burlington and Plainfield, specializes in treating incontinence and pelvic floor disorders in women and is certified in Pelvic Muscle Dysfunction Biofeedback. In Manchester, Kathy Metzger of Metzger and Mole Physical Therapy has a similar practice. Both therapists prefer clients to be referred through physicians, for other causes to be ruled out, and to facilitate insurance coverage. And they both believe that all women can improve their present level of pelvic floor dysfunction with treatment.

Phoenix Physical Therapy is set up like a home, with abundant green plants and soothing colors on the walls. Kaufman and a second physical therapist in the practice, Deirdre Folsom, are committed to putting women at ease, and creating a safe, peaceful atmosphere for women to start the healing process. This, they hope, will encourage more patients like Laura (not her real name).

Laura underwent an emergency hysterectomy that resulted in the inability to urinate or pass stool on her own. She saw a team of doctors and underwent various procedures, all without improvement. She has been unable to work for a year, and must catheterize herself in order to evacuate her bowels. Last year, Laura was referred to Kaufman where for the first time, she said, she experienced a "glimmer of hope." Laura says Kaufman has helped her to see how her mind can control bodily functions, and how to take the shame out of her condition and feel more self-accepting.

"I'm not going to give up," says Laura, "and neither should other women."

Roberta Nubile is a freelance writer living in Charlotte, VT |