Hip to the State of

Orthopedic Surgery

By Amy Lilly

Mary Lou Robinson, owner of the Burlington shoe store Tootsies of Vermont, didn’t even hesitate when her orthopedic surgeon and her chiropractor both looked at an X-ray of her left hip and advised her to get it replaced. During childhood, Robinson had sustained a series of mini-traumas to the hip, including ski and sledding accidents and being hit by a car. In recent years, says the 63-year-old, she compounded those injuries with the simple but repetitive act of getting into and out of her car.

By the time of her visit to Fletcher Allen Health Care’s orthopedics department last year, Robinson says, “I had no hip joint at all. It was bone on bone.” That is, the joint’s cartilage had worn away, causing the ball-and-socket parts to grind on each other. The immense pain this caused grew “exponentially worse” over the next four months until she could get into surgery. She adds, “If it had to have been postponed another couple weeks, I wouldn’t have been able to go to work.”

Despite the wait, the procedure was a success. The shoe maven can now walk and perform everyday motions without pain. “People noticed my face first,” recalls Robinson. “They’d say, ‘You look so young!’ It was the absence of pain on my face.” Eight months after her operation, Robinson still goes to physical therapy once a month, but only to work on her gait and stride. “I’m an orthopedic’s dream,” she says gleefully.

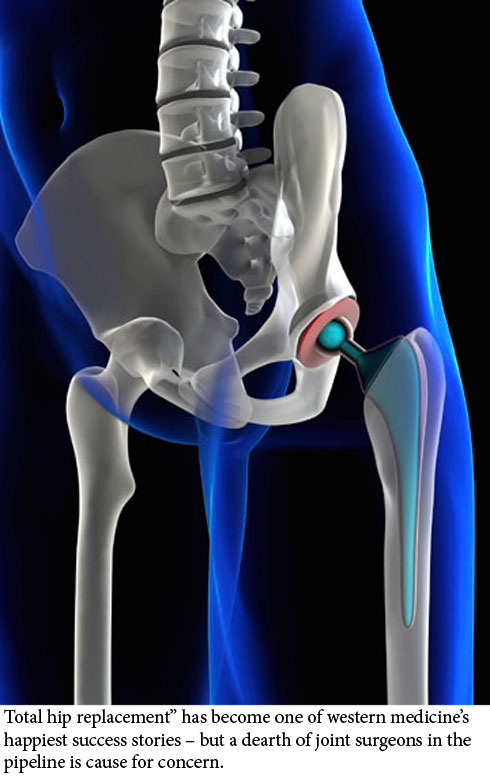

The truth is that Robinson’s positive experience with total hip replacement (THR), sometimes called total hip arthroplasty, is now run-of-the-mill. THR has become one of Western medicine’s happiest success stories. The typical candidate hobbles around for months with chronic hip pain caused, most often, by osteoarthritis – the result of wear and tear on the joints over time. (Other causes include injury, hip dysplasia, and rheumatoid arthritis.) After an hour-long procedure with a 95 percent success rate, followed by a few months in physical therapy, the patient can walk painlessly upstairs for the next 15 years or more.

Such a successful operation was bound to grow in popularity, and it has. Hip replacements are the most commonly performed surgery in orthopedics, the surgery specialty that focuses on the correction of bone and muscle irregularities. Robinson was one of approximately 750 people to receive either a total or a partial hip replacement in a Vermont hospital last year, according to a study by the Vermont Department of Banking, Insurance, Securities, and Health Care Administration. That’s small fry in comparison with national numbers. According to the annual National Hospitals Discharge Survey, approximately 193,000 THRs were performed in the United States in 2002, and by 2006 that number went up to 231,000. Current estimates reach as high as 300,000 surgeries per year.

Women account for more than half of that total every year – somewhere between 54 and 58 percent, depending on the year. Dr. William Lighthart, an orthopedic surgeon with Rutland Regional Medical Center’s affiliate, Vermont Orthopaedic Clinic, believes that one explanation for this is that women live longer. Another oft-cited one is that women are more likely to get hip osteoarthritis, but a 2008 study by the National Arthritis Data Workgroup, funded in part by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health, found that determining the true prevalence of hip osteoarthritis in the population as a whole is difficult given available data – making gender comparisons even trickier to establish. It’s possible that the belief that more women have hip osteoarthritis in itself leads women with hip pain to seek out the surgery more often, or doctors to perform the procedure more readily on women, or both.

Driving the rising THR rates overall are a number of factors that go beyond the procedure’s phenomenal success rate and life-changing outcomes. The primary reason is an aging population. So, while we acquire osteoarthritis at the same general time – in our 60s – we are living with it longer. Aging baby boomers tend to want to maintain their active lifestyles rather than resign themselves to a wheelchair, and THRs enable them to continue snowshoeing and skiing (though not running or any other impact-heavy activity).

A lesser contributing factor is the rise in obesity rates. A 2003 prospective study by the National Institutes of Health suggested that the combination of osteoarthritis and obesity in women in particular results in significantly more hip replacements.

Advances in prosthetics and technique have also driven the numbers. The original hip implants, developed in their current form in the 1960s by British surgeon John Charnley, were once thought to be unfit for people outside a conservative age range and weighing more than 180 pounds. But now doctors trust the implants more, says Lighthart. In the two years he has been in practice, his patients have ranged in age from 13 to 96. (He performs about 100 hip replacements a year.) The original parts once came only in small, medium, and large; now there are a range of sizes and shapes to accommodate everyone from the 400-pound patient to the 90-pound one.

And so-called minimally invasive implantation techniques developed in the last five years, which use smaller incisions, help patients recover more quickly with less torn muscle. The typical hospital stay is now down to two days or less. “Not too many years ago, you’d be in the hospital before the surgery, you’d be in the hospital after the surgery for longer, and you’d be on crutches for six to eight weeks,” says Lighthart. “Now most people can fully weight-bear the next day.”

Expanded indications for the procedure mean that the average patient age is dropping. But the majority of THRs are still performed in patients over 65: as late as 2007, Medicare paid for 60 percent of hip replacements nationwide. It’s ironic that the core of orthopedic practice today is dedicated to prolonging mobility among the aging. Orthopedics began in the 18th century as the correction of bone deformities in children – hence the ring of “pediatrics” in the Greek-derived second half of “orthopedics.” (“Orth” is Greek for “straight.”) Yet it’s also fitting. For as almost anyone who has undergone the process lately will say, the result can make you feel like you’re young again.

On Not Living with Pain

Polly Hennessey, 86, and Madeline Rice, 64, across-the-street neighbors in Bellows Falls, are old hands at undergoing hip replacement. Each woman has had both hips replaced. Sitting on their pairs of prostheses in Hennessey’s living room during a phone interview, they take turns chatting blithely about pain and suffering.

“Initially, with the first hip, I thought I was having a back problem,” explains Rice, who was 62 at the time. For several months she took Celebrex, a prescription anti-inflammatory pain medicine, even though it upset her stomach, and she saw her chiropractor regularly. The chiropractor finally suggested it might be her hip that was causing the trouble. Imaging at Springfield Hospital revealed that both hips had deteriorated.

Rice’s orthopedic surgeon, however, recommended replacing only the worse-off joint, explaining that the longer Rice could use the other hip, the longer she could delay an eventual replacement of the replacement hip – that is, a revision. Hip revisions become necessary as the original parts wear out, usually within 20 years of implantation. The procedure has a lower success rate because the bones have already been tampered with once.

Rice delayed getting her second hip replaced even longer than recommended. It wasn’t the surgery she dreaded – she knew it would do the job – but the recovery process. Rehabilitation can take as long as a year, and includes learning to use special tools to pick up fallen items and pull on socks. As Lighthart sums up the rehab process, “In general, it takes about three months to be 90 percent recovered, and a year for it to get as good as it’s going to get. The majority of that recovery happens in the first several weeks.”

Rice’s pain eventually became overwhelming, though. “I had to walk with a cane from April to August,” she says, describing the final months. “I’m telling you, I was kicking myself in the backside – what did I wait so long for?”

Hennessey agrees: “When it hurts, you can’t get it done quick enough.” The octogenarian had her second hip replaced at Springfield Hospital in May 2009, ten years after her first. Following both surgeries, she says, “I got right up – I was going full blast. You get right up the next day with a walker.” The whole process seems not to have fazed her in the least. Indeed, she says, “Knee surgery is harder because you have to bend them so much.” (Hennessey has had both knees replaced, too.)

Both women urge others with hip pain to avoid putting off the life-changing procedure. “The pain is so bad,” says Rice, “but the next day you step down and the pain’s gone. In the first few days it’s like a miracle. It is unreal, that kind of an operation.

“If anyone is thinking of getting one but they’re hesitating,” she adds with a laugh, “just send them to Polly and me and we’ll talk ’em into it.”

Building a Hip Joint

None of these women could say exactly what kind of prosthesis was implanted in her. That they felt no need to know may reflect the fact that, despite constant tinkering by the medical device industry with new materials and models, the basic prosthesis has remained remarkably constant.

The hip joint works as a ball and socket, with the head of the femur, or thigh bone, shaped like a ball that rotates in an acetabulum, the socket. In a replacement, the femoral head is cut off and replaced with a metal one with a tapered shaft that fits inside the shaft of the bone. The metal femoral head rotates in a plastic cup inserted into the socket.

Technicians have tried various materials. Charnley began with a Teflon acetabular cup but found that it shed microparticles that caused osteolysis, a localized immune response that sometimes leads to the eating away of the bone surrounding the implant. Over the last few years, a ceramic cup and ceramic femoral head became popular – until patients discovered a squeak in their walk. Many doctors no longer use ceramic-on-ceramic implants. Others, like Dr. Christopher Meriam of Green Mountain Orthopaedic Surgery in Berlin, still consider it an option but warn their patients about the squeak. “And it is loud; just go to YouTube,” Meriam says. He points out, however, that ceramic’s higher durability and supposed lower rates of microparticle shedding occasionally make it a better choice for younger patients.

Metal-on-plastic prostheses are the current standard: cobalt-chrome femoral heads with a titanium shaft, and acetabular cups made of a type of polyethylene. Plastic cups, however, deteriorate faster than metal, so a metal-on-metal joint is occasionally used, like ceramic, in younger patients. But the microparticles these shed are still a problem. Metal-on-metal is not recommended for use in women of childbearing age, since it’s not known what damage the particles can do once they cross the placenta.

Getting the assembly to stay in place is another matter. For a long time, cement and occasionally screws did the job. Today, the parts are fitted very tightly and come coated with an “in-growth” surface – which, helped by friction, allows the bone to grow into and attach to the implant over time. However, in-growth surfaces only work on bone that’s alive and growing, so in certain cases – such as the very elderly – cement is still used.

Always looking for a new angle, the medical device industry recently rolled out women-specific hip prostheses. In sum, says a skeptical Lighthart, these amount to certain sizes and shapes that had already been found to be appropriate for women more often than for men. “The issue is misleading in my opinion,” he explains. “Really, it’s whatever fits best. They make women-specific knees, too, and I’ve put those in men. I’m going to use what fits the patient.”

Another recent market offering, resurfacing devices, has proved more ominous for women. Available in the U.S. since 2006, these prostheses have a smaller shaft, requiring removal of less of the femur. The device is intended to give younger patients a way to put off total hip replacement. But a shorter anchor means a higher risk of fracture in patients with weak bones – and women’s bones generally weaken during menopause. Says Meriam, who did his subspecialty training in trauma, “The current indications are that resurfacing is not for women because of the high risk of fracture. It’s specifically for men under 50.”

THR alternatives aside, the range of differences among prostheses on the market remains relatively small. This perhaps explains why all five companies that manufacture 95 percent of the artificial hip and knee joints out there – Zimmer Holdings, Johnson & Johnson’s DePuy Orthopaedics division, Smith & Nephew, Stryker Corp., and Biomet Inc. – were recently discovered to have been paying doctors to exclusively use their devices. In 2007, the federal government completed an investigation alleging that doctors were given a total of $800 million over four years. Rather than face prosecution, the companies paid $310 million in fines and agreed to closer monitoring for a few years by the Department of Justice.

While it’s worth asking your doctor which kind of prostheses he or she favors and why, it’s far more important, says the literature on outcomes, to choose a doctor who has a lot of experience putting them in. A 2001 study in the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery concluded that patients treated by surgeons with higher annual THR caseloads had lower complication rates, and a 2004 study in Arthritis and Rheumatism: The Journal of the American College of Rheumatology found that patients treated by low-volume surgeons more often needed a revision within the first 18 months after surgery. The latter study warned, “Referring clinicians should consider including surgeon volume among the factors influencing their choice of surgeon for elective THR.”

And that’s where a looming problem comes in.

Where Are All the Joint Surgeons?

A hip replacement typically runs to $30,000, and revisions cost even more. A majority of these procedures are covered by Medicare reimbursements to the doctors and hospitals. Over the last decade, however, those reimbursements have actually decreased even as the procedures’ costs have risen, mostly due to the rising prices of ever-more-refined implants.

This prospect of decreasing revenues has caused many orthopedic surgeons in training who are considering a subspecialty to opt against joint replacement in favor of more lucrative choices, such as sports or spine orthopedics. Teaching hospitals are finding it difficult to fill their joint replacement fellowship positions. And the number of these positions, as dictated by the American College of Graduate Medical Education, has remained the same for years.

The slowing trickle of joint surgeons in the pipeline is already starting to alarm the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, which hosted a panel at its 2009 annual conference entitled “Joint Replacement Access in 2016: A Supply-Side Crisis.”

Even joint replacement surgeons currently in practice are limiting access: some are opting not to accept Medicare patients, in states where it is legal to do so. It’s illegal in Vermont – and that puts lower-volume practices like Green Mountain Orthopaedic Surgery in a difficult position. According to Meriam, who performs approximately 30 THRs per year and has been in practice for 14 years, “Government has decided health care costs too much, and their idea of cost control is to pay less. There may be other rationales, but that’s what I can see. Those cuts seriously affect my ability to practice and pay my employees. I can’t cut my employees’ salaries every time the government decides to lower reimbursements.”

As the pool of joint surgeons shrinks, what will happen to those soaring numbers of Americans who need artificial hip joints? “It’s going to be an epidemic soon,” declares Lighthart. “Talk about health care reform: this is one of the areas where people are going to start to see long waits.” Equally concerning to him is the prospect of hip revisions, the need for which will increase as hip-replacement patients become ever younger. Revision surgery is one of the most technically demanding available, and fewer surgeons will have the subspecialty skills to perform them.

One may wonder why orthopedic surgeons go into joint replacement at all, when they might be earning much more performing spine operations. Lighthart explains, “I didn’t pick it based on making the most money. I picked something I thought there was a very large need for, and the patients in general are very happy. Someone who’s had [a THR] done feels good to great two days out. For me, it’s fairly instant gratification. Also, I like the technical part of the surgery, though that’s secondary to the fact that I really like what this does for patients. I think it’s a great thing.”

Mary Lou Robinson couldn’t agree more. Her artificial hip may have limited the range of shoes she can indulge in – she now wears “sensible yet fashionable” flats or sneakers with orthotics, but never heels. “Nor will I ever,” she adds.

But otherwise, she declares, “I’ve got everything back except all my moxie.”

(See related story below, “Hip Replacement Surgery: The Next Step, Rehab and Going Home”)

Associate Editor Amy Lilly lives in Burlington.

|