Reproductive Health Care 2011:

Itís About Access

By Cindy Ellen Hill

First, the good news. On August 1, 2011 the Department of Health and Human Services adopted a mandate that private insurance companies provide coverage for eight critical preventive reproductive health services without cost-sharing, i.e. co-pay requirements. The new Family Planning Option of the Medicaid program, adopted by Vermont this summer, expands coverage for these services for lower income women as well. These services include an annual well-woman visit, gestational diabetes screening, HPV DNA testing, STI and HIV screening and counseling, breastfeeding supplies and support, and birth control counseling and supplies.

This expanded realm of economic access to preventive reproductive health care for women is scheduled to go into effect in August 2012. (Just some of) the bad news is that the span of time between now and August 2012 stretches like a wide, hot and hostile desert inhabited with political, economic, and state-level legislative attacks being waged against women’s access to reproductive health services. It will be a long hard walk across that desert, including the need to navigate a baffling wilderness of state and federal health care reform, and when we get there, we may find that the shriveling economy has withered the promised oasis of progress to a desiccated mirage.

Or we may find that the well of reproductive health care promises has been fulfilled sufficiently to fortify us for the next battle: the 2012 election, when many things stand to be lost, or won, or pushed back for yet more continued fighting into the future. This trek is all about access – and it won’t end soon.

Federal Fights

Federal programs and money affecting reproductive, maternal and infant health exist in numerous different streams, each with their own restrictions and regulatory requirements. The Affordable Care Act and insurance regulation affects what reproductive health services private insurance companies must or may cover; Medicaid and a variety of Medicaid waiver and option programs provides funds for reproductive and preventive health services through state-administered programs that benefit individuals based on their low-income status; Title X funds support facilities that provide family planning services with priority to low-income and underserved populations; and the Women, Infants and Children or WIC program provides funding and support for food and some limited health care services for pregnant and post-partum women, infants and children to age five through the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Not a dime of any of that federal money can go towards abortions or abortion-related services. “No federal money goes to abortion, it is all for preventive services,” says Jill Krowinski, director of Vermont Public Policy for Planned Parenthood of Northern New England (PPNNE). “It has nothing to do with abortion. None of the federal programs, Medicaid, Title X, WIC, can go towards abortion.”

The assertion that it has ‘nothing to do with abortion’ is not one of universal agreement. Federal funds have been prohibited from use in abortion services since the 1970s, sparking ongoing controversy around entities like Planned Parenthood that provide both federally funded services, like family planning, and services prohibited from receiving federal funds, like abortions. After the 2010 mid-term elections, the Congressional budget debate came to focus on this distinction as a contingent of Republicans, primarily Tea Partiers, pushed to defund Title X all together on the grounds that a substantial portion of Title X funds go to Planned Parenthood and its affiliates across the country.

Title X Family Planning Program of the Public Services Health Act of 1990 is the sole federal program specifically dedicated to family planning and related preventive health services. It is administered by the HHS Office of Population Affairs. Title X receives federal line-item budgeting; in 2010 Congress allotted $317 million for Title X funds. According to HHS, more than five million men and women received Title X supported services at over 4500 community based health facilities in 2010. Although Title X funds can be used for health care personnel training, data collection, and community education and outreach, 90 percent of the funds go to subsidize direct services, with a priority for assisting low-income patients. However, unlike Medicaid funds, which are targeted to an individual based on that individual’s income status, Title X funds go to facilities to insure family planning services access in areas that may not otherwise have such services. Over 75 percent of U.S. counties have at least one Title X supported facility.

In April 2011 Congress passed the federal budget, but only after pulling out the Title X defunding issue to a separate vote in which the defunding was narrowly defeated. The threat to Title X passed the House, but was defeated in the Senate 42-58. Vermont’s U.S. Senators Patrick Leahy (D) and Bernie Sanders (I) both voted in favor of maintaining Title X funding, and both issued strong statements in favor of continuing funding for family planning services generally and Planned Parenthood specifically. Six Republican senators also voted in favor of continuing Title X funding. In the end, the program was level-funded at $317 million for 2011.

The federal Affordable Care Act health care reform, which addresses private health insurance rather than publicly subsidized health programs, was signed into law on March 23, 2010. Some of its structural provisions – such as protection against getting dropped from health insurance policies and the requirement that children can remain on parents’ health insurance policies until age 26 – have already gone into effect, but the bulk of the substantive provisions are still working their way through the Department of Health and Human Services regulatory process. Amongst its other provisions the ACA requires mandatory no-co-pay coverage of preventive and reproductive health services including paying for birth control.

The Department of Health and Human Services also implemented a new Medicaid Family Planning option waiver that allows states to opt to expand family planning coverage. “Every dollar invested in family planning saves $3.35 in other publicly supported services that would otherwise be paid out,” says Krowinski. HHS apparently understands that investment, and has found provision of family planning services to be cost effective, according to implementation guidance documents issued by the HHS Center for Medicaid, CHIP and Survey/Certification.

One major unanswered question is how expanded private and Medicaid coverage for reproductive health services is going to affect other funding streams. “The interesting thing for me is when they go to expansion of women’s reproductive health coverage, what is going to happen to Title X coverage of women not qualified for Medicaid who are on a sliding scale?” asks Wendy Love, executive director of the Vermont Commission on Women (VCW), who formerly worked in community health care policy and administration in New York State. “The Title X funds were grants, not tied to the person’s individual economic status like Medicaid qualifications, but grant funds to the facility. There are also Federal Qualified Health Center Grants. What’s going to happen to these as we expand the Medicaid coverage?”

At risk is access to reproductive health services for people who may not qualify for Medicaid but who are nonetheless caught having to choose between paying for birth control, food, or heat in tight economic times. The men and women caught in that hinterland may well increase as the “SuperCongress” budget-slashing committee created out of the Congressional debt-ceiling debacle puts everything, including Medicaid, on the chopping block while unemployment shows no sign of abating and the circling vultures of financial commentary croak about a potential double-dip recession.

Public support for reproductive health care is critical given that the present private health care business model does not begin to provide adequate and necessary services. “The private insurance companies assume seven minutes of service per patient, and for an educated, sophisticated person with resources that may be sufficient,” Love explains. “But with women of humble circumstances, or who are scared and facing something unknown or have questions, that won’t be enough time. When I worked in this field, private doctors would say to me, ‘I don’t get reimbursed enough to provide these services.’ It’s not that they don’t have the knowledge or even the desire to do it but they don’t get reimbursed enough to make it work economically for their practices, and that’s where the family planning organizations and clinics come in that are willing to do this. One of the things that is scary about healthcare reform is how that will affect the service to lower income women or patients who need more than that seven minutes that private doctors provide.”

VCW will be among the parties watch-dogging each proposed health care system change as it comes down the pike. “What you always want to make sure is that women have access to high quality reproductive health care and a full range of health care services,” Love says. “As each new policy or plan comes down we need to evaluate it carefully for unintended consequences.”

State Erosion

Meanwhile, the federal saber-rattlers who did battle over Title X funding in Congress this year did not pack their swords quietly and go home. They moved to state battlefields, where those fighting to restrict abortion access through regulation and funding made substantial inroads, creating hurdles to reproductive and preventive health services in some instances along the way. “State by state we have never seen erosion like this,” says Krowinski.

In the first six months of 2011, 19 states enacted 162 new provisions relative to reproductive health and rights, according to the Outmatched Institute, a nonprofit organization founded by physician Allan Guttmacher in 1968 to provide research, policy analysis and education regarding reproductive rights and population issues. About half of these restrictions explicitly address abortion access. In 2011 alone, five states adopted abortion counseling and waiting periods, 15 banned abortions after 20 weeks, Ohio banned abortions after a fetal heartbeat can be detected, eight states adopted restrictions on private insurance abortion coverage in their implementation of the ACA, six states sought to preclude medication-induced abortions, and five states banned the use of telemedicine in the course of abortion provision. At least nine states enacted deep cuts in funding for family planning services, though many of these were on par with their cuts for other services due to severe budgetary difficulties.

Five states restricted funding for family planning services providers in the first half of 2011. Planned Parenthood is the primary entity affected by these restrictions. Colorado, Ohio and Texas already had long-standing restrictions against any state funding going to any entities that also provide abortion services. Indiana and Wisconsin both adopted similar provisions. North Carolina skipped the semantics and explicitly adopted a provision prohibiting Planned Parenthood and Planned Parenthood affiliates from receiving any state funds. Kansas adopted legislation prohibiting distribution of Title X funds to family planning centers, while Texas stated that family planning facilities are the lowest priority for Title X funding.

Bills requiring facilities that perform abortions to have hospital affiliations were considered in 11 states and adopted in two in 2011; Florida, North Carolina, Texas and Utah adopted legislation approving issuance of ‘Choose Life’ license plates; eight states passed laws restricting private insurance companies who participate in their health insurance exchanges from covering abortions to limited cases of rape or life endangerment. State abortion bans were proposed in 20 states and one made it onto the ballot in Tennessee, where it will be publicly voted at this November’s election; if approved it would state that there is no right to abortion under the Tennessee state constitution. Regulations targeting funding were proposed in 19 states and passed in four – plus New Hampshire, which does not make the list as it was a contract defunding by the Executive council, a unique political form and not an act of the legislature.

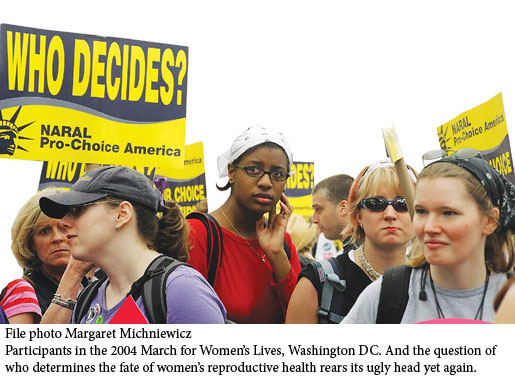

“What is disconcerting is that we are seeing this as a national strategy. In one short election, that’s all it takes,” says Laura Thibault, interim director of NARAL New Hampshire. “Women in every state need to be politically active. This one election gave them the power to make these changes.”

Case In Point: New Hampshire

New Hampshire’s Executive Council is an elected body of five people from districts across the state. All five seats are presently held by white Republican men. Among the Executive Council’s tasks are approving the contracts with entities willing to provide reproductive health and preventive services to Medicaid recipients. This year the Executive Council disapproved the state contract with PPNNE.

There are 10 contracted reproductive health service providers in New Hampshire, and the Executive Council “dropped only PPNNE, specifically because they are also an abortion provider,” says Krowinski. “PPNNE has six facilities in New Hampshire. Three of those are [along] the Connecticut River. 1500 women from Vermont are patients at these facilities.”

The vote to drop PPNNE’s contract, which has been approved every two years since 1970, was 3-2.

“This is a routine contract that has come before the council for 40 years,” Thibault says. “Not everyone is willing to provide services for low income women.”

Councilor Christopher Sununu, an environmental engineer, ski area owner, son of former Governor and Chief of Staff for the George H.W. Bush administration John Sununu and brother of former U.S. Senator John E. Sununu, was one of the two who voted in favor of continuing the contract. Sununu is no fan of Planned Parenthood, he wrote in a July 24, 2011 opinion piece in the Manchester Union Leader. However, he called his vote “the right thing to do” to provide necessary basic health services to disadvantaged women.

Executive Councilor Raymond Wieczorek, however, couched his vote to discontinue the Planned Parenthood contract in different terms, telling a reporter from the Concord Monitor that public funds should not cover contraception at all, and “If they want to have a good time, why not let them pay for it?” The other two of the three councilors who voted to defund PPNNE were clear in public statements that they did not oppose preventive and contraceptive services, but rather were casting their votes to because they did not support entities that provide abortion services, even though these funds would not be used for those purposes. However, the reasoning of all three raises the frightening spectre of a concerted effort to bring pressure to bear on abortion service providers by waging war on access to basic necessary health care for all women, particularly those of limited economic means—a growing constituency in today’s economy.

The Federal Medicaid funding contracts with the states requires that services be provided geographically across the entire state. “PPNNE covers half the state of New Hampshire,” Krowinski says. “Without PPNNE, they are in violation of the federal contract by not providing geographical coverage.” New Hampshire had until August 15 to provide evidence to HHS that they had a plan in place for full state coverage. They did not do so, leaving HHS with the options to ignore the situation, pull all Medicaid family planning service funding from the state, or contract directly with PPNNE themselves. As of this writing, no public indication had been made of a resolution but the Concord Monitor reports the potential for a revote on the contracts given some technical irregularities that were discovered in the course of public scrutiny of the voting process.

For the moment, the six New Hampshire PPNNE facilities are still open and seeing patients. All are staffed by RNs and NPs, and two provide abortion services. But the 68 percent of PPNNE patients who are either covered by the state funds, or not covered by the state but pay on a sliding scale, which PPNNE can provide, based on donations and other funds raised to subsidize their services and products, are affected by this vote.

“It’s been a tough legislative session,” says Thibault. In addition to cancelling the PPNNE contract, the New Hampshire legislature passed an act requiring parental notification for abortion for anyone under 18: “For women under 18, they must notify parent or legal guardian or they have to navigate the court system.”

“It’s really preventative services that it’s hindering, as the federal contract does not pay for abortion,” Thibault says. “They are just making it harder to access contraceptives, and one question you have to ask is, will that just increase abortions down the road? Access to birth control is one of the ways we can prevent abortion. We have noticed that it’s a really galvanizing issue – New Hampshire historically has been a fairly friendly place for women, usually represented by moderate, pro-choice republicans. Now it feels like there’s a real harsh tone against women.”

Vermont

Vermont, too, has been a friendly place for women – and so it remains. While the funds hold out.

Anyone who lives in Vermont knows the state is a unique environment in many ways, but many of the state’s citizens may not realize that some unusual agreements with federal health-care funding programs play critical roles in the state’s medical and economic landscape.

Vermont has long had a one-of-a-kind Medicaid long-term care waiver, which has allowed the state to structure elder, care with an emphasis on in-home care. In the fall of 2005, Vermont secured a Global Commitment waiver, also the only such program in the nation, in which Vermont receives a set capped amount of Medicaid funding with waivers of some of the federal standards, that allows Vermont a great range of flexibility in structuring its in-state Medicaid benefits distribution structure—including using Federal Medicaid money for state non-Medicaid health care programs like Catamount and Dr. Dynasaur.

“Vermont got good terms with Global Commitment,” says Wendy Love, who wrote a plan similar to Global Commitment while working as a primary care planner in upstate New York for a public/private health systems agency. One-quarter of Vermont’s population, and over one-third of Vermont’s children, are covered under Vermont’s Medicaid-funded health care provisions, according to an April 2006 Issue Paper of the Kaiser Foundation’s Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured.

In 2011 Vermont adopted the Medicaid Family Planning option, which “entails an extension of benefits of family planning services to be implemented in 2012, but we’re gearing up for it now,” explains Lorraine Siciliano of the Department of Vermont Health Access Division of Health Care Reform. That gearing up includes a public meeting August 30 and a time period for public comment on regulatory implementation. The new option allows states like Vermont to extend family planning services to people who otherwise are not qualified for Medicaid as they don’t meet the income eligibility guidelines.

Vermont Right to Life will be amongst the interested parties playing an active role in that implementation process. “The State of Vermont under Supreme Court order pays for abortions for low-income women. Under the Vermont Health Care bill, there is this new program for family planning. If it includes abortion, that would be an expansion of taxpayer-supported abortions,” says Mary Hahn Beerworth, executive director of Vermont Right to Life, referring to the fact that the program may extend state funding of abortions to women who are not presently income-eligible for Medicaid. “We want clarification on what is meant by family planning. We have no position on true contraception services. We are not opposed to contraception. And we are not opposed to expansion of family planning services, including fertility counseling and adoption programs.”

Vermont Right to Life does not anticipate repealing the Vermont health care reform measures. “We don’t have the votes,” Hahn Beerworth says. “But we will be working to insure that there is a definition of family planning.” That work will also be aimed at insuring “that people are not denied health care on the basis of income, age, disabilities, or economic status,” Hahn Beerworth says. Noting that one in five Vermonters has some form of disability, Vermont Right to Life expresses concern that some single entity payer health systems like Oregon has appear to ration certain health services based on fiscal considerations.

The Family Planning option does appear to leave considerable room for defining the services covered to the states, although the sweeping federal prohibition against using federal funds for abortion services is likely to apply. HHS notes that “Family planning-related services have historically been considered those services provided in a family planning setting or as part of a follow-up to a family planning visit,” giving examples of treatment for STDs and STIs, annual physicals for men and for women, treatment for urinary tract infections, and vaccinations intended to reduce cervical cancer risk. Vermont is considering expanding eligibility for this option to 200 percent of the federal poverty limit. States also have the option of considering just the individual’s, rather than the household, income for this program.

PPNNE and other family planning service providers will also be keeping a keen eye on developments in the adoption of the Family Planning Medicaid option. Seventeen states including Vermont allow use of state – not federal – Medicaid funds to subsidize abortions for low-income women; Vermont’s funding is among the least restrictive of these. In Vermont, PPNNE operates 10 facilities, four of which provide abortion services, but only to 15 weeks after gestation. PPNNE does not provide what is commonly called second trimester abortions, and Krowinski was unaware of a provider in state.

There are about 225 abortions in Vermont for every 1,000 live births in 2008, the most recent year for which Vermont Department of Health Vital Statistics are posted. Thus for 6,341 babies born in Vermont in 2008 there were about 1420 abortions. This rate is on par with the national average for the United States, though the number of abortion providers in Vermont is diminishing, according to PPNNE.

The future of access to abortions as well as a broad array of reproductive and preventive health services for men and women in Vermont will turn on the issues of federal funding, the outcome of the next Presidential election, and how Vermont handles its move towards single-payer health care.

Future Access: Where’s the Money?

In less than 18 months, the federal government will have issued the totality of its initial implementation regulations on the Affordable Care Act, and Vermont will have engaged in its implementation of the ACA and the Medicaid Family Planning option, and taken up single payer healthcare and passed some manner of budget. Vermonters and the rest of the nation will also have lived through another Presidential and Congressional election and a series of federal cost-cutting measures mandated by the agreement reached to secure the vote raising the federal deficit ceiling.

“The next election is critical,” Krowinski says. “All this defunding and attacks in the states came after only one election that changed the face of things. This next election and then the first vote in Congress after that election could be to try to remove the ACA. We will have to be very proactive. Vermont women are affected by what happened in New Hampshire. There are attacks on access to reproductive health services at the federal level. Even though in Vermont we are fortunate to have access, we can’t take it for granted.”

That access is going to come with an increasingly high price tag. “The biggest change due to the Affordable Care Act that will happen in Vermont is that Vermont will be creating a health insurance exchange, as other states have done,” says Jeanne Keller, a proprietor of the consultancy Keller and Fuller Inc., which reviews health care policies for clients such as the Business Resources Services, a health insurance purchasing plan for small businesses. “States have the option of either letting the feds do it or running their own, and Vermont has opted to run our own. That raises a couple of things. In early October, the feds will be releasing their National Essential Benefits plan list. That will be the list of minimal benefits that any health care insurance plan has to have included. That defines the floor, the very first time we will have a federally mandated floor. This applies to any privately sold insurance. States then adopt the federal floor and can choose to make it richer.”

Each state will have to decide whether to include additional services in its coverage. “We already had big benefit mandates in Vermont, including autism disorder treatment, mental health parity way beyond federal recommendations, and coverage of experimental procedures such as stem cell treatments,” Keller says.

The basic reproductive preventive health services already announced is likely to be on the federal mandate list. However, “Once the feds issue their floor, that’s what the federal subsidies will cover. So the state has to cover anything on top of that. If our state legislature decides we want to cover abortion services, or any other services, we will have to pay for that. The Shumlin administration made it clear that they intend to have one carrier and put every business under 100 employees and all uninsured individuals in Vermont on that one carrier, so 95 percent of all working people in Vermont will now be on the exchange plan exclusively. Everyone who goes into the exchange, we need to be able to cover and for state taxpayers to pay the subsidies. And the Legislature in 2012-2013 will have to adopt a budget that pays for that.”

Those subsidies have to take into account the fact that health care does not dovetail neatly with state borders. “All the models we get compared to regarding a single-payer system are national, federal uniform systems,” Keller says. “But Vermont can’t tax a business domiciled in another state. We can’t tell Dartmouth Hitchcock what to charge us, and half the money at Dartmouth Hitchcock comes from Vermont. And half the cardiac patients at Fletcher Allen [Health Care] are from upstate New York.”

It remains to be seen how this will parse out, but in Vermont, as in the rest of the nation, reproductive health care access is coming down to money—a commodity that is becoming as rare as water in a desert. “Roe v. Wade is still the law of the land, but there are a million different ways to whittle it down,” says Thibault of NARAL New Hampshire. Political defunding efforts are one of the ways to whittle down reproductive health care access – but a collapsing economy, rising national debt, rising unemployment, and shrinking consumer confidence can accomplish the same ends. As dollars shrink and economic and political heat rises, the scramble for reproductive health access is bound to become more desperate and passionate than has yet been seen.

“It’s one person, one vote,” Thibault says. “Know where your candidates stand on these issues and get active. This isn’t an issue that is going to go away.”

Cindy Ellen Hill is an attorney and freelance writer in Middlebury.

|