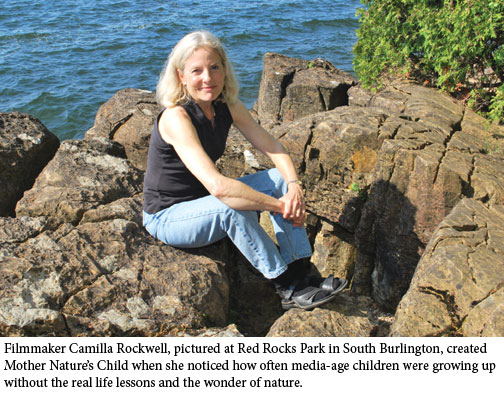

Vermont Filmmaker, Camilla Rockwell: Media Age Children’s “Nature Deficit Disorder”By Roberta Nubile

For those of us 40 and older, who grew up in rural or suburban areas, our childhood memories of outdoor play go something like this: We’d roam our neighborhood freely looking for adventure, build a fort in the woods, hunt for critters, play make-believe games with birch bark or acorns or mud, climb trees and fall from them, jump into a game of stickball or four-squares or hide-and-seek, spend time with a book or just alone with our thoughts. We had spontaneous interactions with other children and adults. We’d spend hours without any contact with our parents, as long as we were home in time for supper. For better or for worse, much of our time was unscheduled and unmonitored. And yes, there was risk inherent in our play. With the proliferation of cell phones and computers, organized playtime and sports, and the fear of “stranger danger,” all that has changed. Today, youth between the ages of eight and 18, according to a Kaiser Foundation Study, may spend as much as eight hours per day in front of a screen, whether a television, computer or a video game. The cultural term “helicopter parent,” now part of our vernacular, describes a mom or dad, who hovers protectively over today’s child, reducing the possibility of physical or emotional injury. This relatively rapid shift in what playtime looks like in our culture, and how it affects every facet of our health, human evolution, and our connection to the natural world, is the subject of Vermont filmmaker Camilla Rockwell’s latest documentary, Mother Nature’s Child.

Beginning Again The seed for Rockwell’s film took root not long after the birth of her first grandchild. She talked about this from her office in Burlington, where she heads Fuzzy Slippers Productions. “I suddenly looked around,” she said, “and noticed the way my grandson was growing up, so different from the freedom I had as a child. I tried to understand what had changed. I hadn’t really thought about it for a while, as it had been a while since I brought up my own kids.” While browsing in a Seattle museum store, Rockwell picked up Richard Louv’s book, Last Child in the Woods. She read it on the plane ride home. “I knew this was the next project,” she said. “I had just finished Holding Our Own: Embracing the End of Life, a film about death and dying. I had gone deeply into that territory. “I was ready to look at the beginning of life--childhood! Mother Nature’s Child felt like a refreshing ‘bookend’ project to the film on death, a way to reconnect to the pure wonder and joy of life through children. Both projects are dear to my heart.” Rockwell’s use of personal curiosity as the impetus for story ideas is her typical process. She likes to clarify that she doesn’t identify herself as a professional filmmaker. “I am sharing my personal journey. I use film to learn about what interests me in the moment.”

Is Nature Necessary? Before the fundraising and filming process began, Rockwell spent a year researching modern perspectives in nature theory. “I’d spent much of my early adulthood with an interior, contemplative focus, naively assuming that ‘environmentalists’ would take care of the outer world for the rest of us. I hadn’t read much about the environment.” What Rockwell learned about nature theory surprised her. “It wasn’t a scolding tone, but more about the innate relationship between humans and the natural world; how we are interdependent and how we need nature.” As a devoted meditation student, the connection between the inner and the outer world mirrored Rockwell’s own approach to life.

Natural Needs This “aha!” moment crystallized the film’s tenor for Rockwell. “The public knows the [environmental] problems well, but our behavior does not change--which is the biggest problem of the movement. I didn’t want to make a film based on scary, depressing aspects and leave people agitated, or hopeless. I wanted to give people a sense of coming out of the film as if they themselves had some contact with nature, and edit it at a pace that would match the way the nervous system takes in info.” The lush images and sounds of the outdoors—along with inspiring scenes of dedicated teachers who guide young people, toddlers to teenagers, in the natural world—results in a sensual film that offers the viewer answers to a growing problem; Louv calls it “nature deficit disorder.” How to rein in such a potentially far-reaching topic came next. Rockwell identified several key issues that the film would focus on: an increased and arguably irrational fear of child abduction, which prevents parents from letting children roam freely; unstructured versus scheduled play; how to get youth, including inner city kids, connected to nature; balancing technology and screen time; and the importance of risk-taking in building resilience and problem-solving skills in children and adolescents. She structured the film in segments, depicting issues pertinent to early and middle childhood and adolescence, and overlaid with a framework from Stephen Kellert’s work out of Yale Environmental School. He documented an innate human fascination with nature, an instinctive bond, and named it “biophila.” In his book Children and Nature, Kellert describes how the lack of exposure to nature affects human cognitive and affective development.

Mother Nature’s Child does not explicitly state that an overuse of media and technology, coupled with a loss of unstructured play and outdoor time, results in issues affecting today’s children. These include obesity, early-onset diabetes, depression, suicide, aggression, learning and attention disorders, and an inability to navigate social relationships or problem-solve. However, the film asks us to connect why these things are happening simultaneously. “All the skills that children get by just playing [outdoors] are being lost in an incredibly short time,” Rockwell explained, “faster than the organism can evolve and catch up. What the culture wants, such as getting into the best colleges, creates pressures for children to excel academically. And they are losing childhood altogether. Researchers are recognizing how important play, especially play in the natural world, is to the development of the human being. It’s seen in all animals. Play is a necessary stage of development. We don’t yet know the results of that loss.” The film gives examples of how climbing structures at playgrounds with perfectly smoothed and spaced handholds does not serve the brain’s fine and gross motor development in the same way that navigating the uneven natural world does. Nor does it afford the same sense of discovery. “My main concern,” said Rockwell, “is we have a generation of children growing up without wonder and awe—and what kind of a life that will look like.”

Project Partners This film was Rockwell’s first project coproducing with another woman, Wendy Conquest. Both had worked with male filmmakers, and had worked together before on films with Ken Burns. “We hadn’t been in touch for a while, and had a wonderful time getting reacquainted by working together. We each wanted to approach the subject with a slightly different focus, so the project wasn’t without occasional creative tension. But that’s how a good film gets made! We developed a strong trust and willingness to really listen to each other’s ideas. We share a similar work ethic—which often meant having to remind ourselves to eat or go to bed!” Rockwell described Conquest’s ease with the technological aspects of filmmaking, including editing and software, but says her own focus was on the emotional response to the film. “I wanted it to allow people to recall memories of their childhood,” said Rockwell, “and to remind people who work for environmental organizations of the reason they got into this work in the beginning.” For Rockwell, getting the film to those other than “the choir” has been the most recent challenge. Several screenings around the world have resulted in lively discussion. Common responses range from motivating to inspiring to thought-provoking, to list just a few from the viewer comments section of the website of Mother Nature’s Child. It is Rockwell’s hope that the emotional response inspires action.

Adult Education It has motivated many already, including Tamie Yegge, manager of the Powder Valley Conservation Nature Center in Kirkwood, Mo. Yegge sent Rockwell a long email about using the film not only to train staff, but also to form focus groups that examine adult comfort levels with children’s unstructured activities. The Center showed clips from Rockwell’s film, with children climbing trees, or crossing stream banks free of adult supervision—and recorded the reactions of parents as they thought about their own children. “It is amazing to see some of the resistance we've gotten during these focus groups regarding that type of play,” Yegge said. “Some parents see it as dangerous and scary. Yet they see TV and video games as safe and nontoxic activities for their children. Once they see some of the facts and information related to the value of nature-play and the detriments of screen time, they seem to pay attention and look at things differently.” She also reported a surprising insight into how staff and volunteers were operating the Center. “It was very eye-opening,” said Yegge, who came to see that their methods contradicted their mission of educating people about nature. “By our actions we were telling them not to enjoy nature. Be afraid of it. Don’t be curious.” She explained that staff and volunteers “were used to imposing rule enforcement, which was very negative and somewhat frightening to children.” Messages common at nature centers, such as, "Stay on the trail," or "Get down out of that tree," or "Don't get wet in the creek," or "Put that turtle back where you found it,” did nothing to encourage healthy risk-taking or spontaneous exploration—the kind of nature-play that Rockwell’s film advocates. Yegge credits Mother Nature’s Child and Rockwell’s visit to the Powder Valley Center with inspiring “a whole new philosophy,” noticed and appreciated by visitors and other environmentalists. Committed to sharing Rockwell’s thinking about the essential needs of children, and all human beings, Yegge distilled the film’s importance. “We have enlightened many other people with what seemingly should be a very simple message: to go outside and discover nature.” Mother Nature’s Child can be ordered directly from its website, www.mothernaturesmovie.com/

Roberta Nubile is a freelance writer in Northern Vermont who still loves to play outdoors. |