Transforming Trash into Art Treasures by Ginny Sassaman - Photos by Jan Doerler |

|||

|

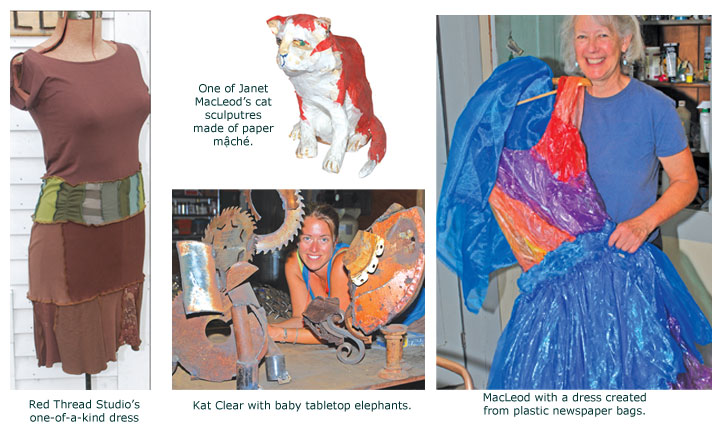

Kat Clear travels to metal scrap heaps throughout Vermont to ferret out old farm equipment and historic junk to carry back to her Burlington studio, where she infuses the metals with new sculptural life. Janet MacLeod can just go downstairs from her studio to the Adamant Co-op, with its barn full of old wood and broken chairs ready for the junkyard — or, in her hands, ready to become art. Janice Lloyd organizes community clothing swaps in Plainfield, and ends up going home to repurpose leftovers into wearable art at her Red Thread studio. The way each woman procures her raw material shows how very unlike they are. And yet all three artists are shining examples of a determination to create a unique life and art. Each has vision, talent, skills and experience that remind us of a world of daily possibilities, turning discarded materials into objects of beauty and utility. |

||

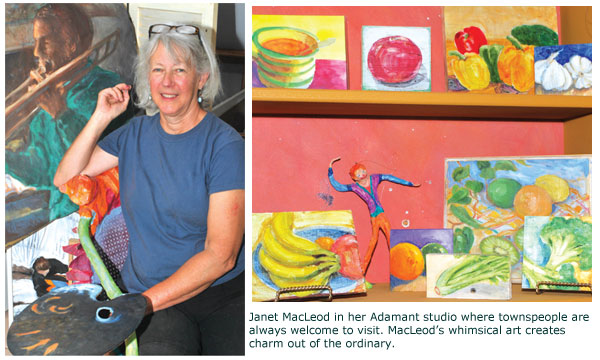

The Happy ArtistWhen Janet MacLeod was a shy teenager, a popular girl told her, "You're really pretty when you smile. " Naturally, wanting to be considered pretty by her peers, MacLeod began to smile a lot more. The smiling led her to feel better, and others responded positively. To this day, MacLeod smiles frequently, as she goes about her optimistic, relaxed life. She laughs when comparing her own way of being with her husband, a former pilot. A linear thinker, she notes, he's concerned with getting from Point A to Point B. "I'm the complete opposite, " she says. "I don't care when I get there, I like the path. " Similarly, MacLeod is determined not to take art too seriously. Despite her B. F.A. from the prestigious Rhode Island School of Design, where she majored in painting, MacLeod has no interest in elevating herself as "the artist with the degree. " When complemented on her "light touch" in her painting and paper mâché, she laughingly ascribes that to laziness. MacLeod can admire huge ideas that entail extensive planning and many workers — like building a bridge — "but then there's doing it yourself, a little idea, a nice idea. It doesn't take much to make people smile. That's a motivation. " Ten years ago, she and a friend curated a joint exhibit around the theme that "Everything we do can be artistic and creative. " The same seems to hold true for her materials. Where others might see broken chairs, she sees creative potential for a Sun King or paper mâché cats. Planks of old wood in the co-op barn? The perfect canvas for paintings of fruits and vegetables. Old maps? Just the thing for more paper mâché — cats, perhaps, or sea turtles. The netting onions are sold in? Reborn as a bouquet of flowers. "Everything can be artistic and creative, " she says. For Janet MacLeod, being green is a nice byproduct but not a primary motivation in reusing materials. MacLeod enjoys taking little scraps of things and seeing what she can create, rather than using huge amounts of resources. "The idea of having to make something out of what you can find challenges your creativity and makes it more satisfying than just buying everything, " she say. "Give me scraps. Abundance is overwhelming. " Another reason for using old materials? She's cheap. Her frugality stems in part from a simple, and sometimes poor, lifestyle, a deliberate choice. She doesn't like working with galleries, and she will not let money be the driver behind her art. "People get frustrated trying to be an artist, and trying to make money at the same time, " she observes. "I never wanted to attach that to my art. I never wanted to feel resentful of my art if it didn't make money. Getting to do what I want is the payment. " If spending money doesn't make her happy, what does? Like many Vermonters, her happiness is rooted in her place. Her roots give her artistic freedom. She grew up in East Montpelier, and her studio above the Adamant Co-op straddles her home town and Calais. Both communities have an open invitation to come visit her while she works. The combination of private space and community energy, along with the immediate feedback she gets for new creations, has helped MacLeod be freer and have more fun in her work. |

|||

And then there's her ability to see the sunny side. Earlier this summer, she went to Scotland, sketchbook and camera in hand. When she got there, the camera died, and for a split second MacLeod was dismayed. Then she thought, "Oh good, my camera died, I'll have to draw everything. " She makes do with what she has — and enjoys it. To view some of Janet MacLeod's paintings and other works, visit www.adamantcoop.org/MacLeod.php |

|

||

|

|||

|

Woman on the MoveKat Clear can be thought of as yin to Janet MacLeod's yang. It's not that Clear isn't happy — she is upbeat, with a huge, infectious smile. At the same time, Clear is a busy, intense, physical, energetic and ambitious woman. While MacLeod enjoys creating small, accessible works, Kat Clear works big. She is currently displaying "Circus Elephants, " three life-sized re-creations made out of wheelbarrows and old oil tanks, at the Shelburne Museum. Another example sits outside her studio: a full-sized sofa crafted from used scrap metal. Her elephants look cheery and her sofa appears comfy, thanks to Clear's magic for combining hard materials with softer concepts. She takes pride in that accomplishment. "Big metal pieces, or small pieces — people might collect them, " Clear observes. But they can't create art with the metal, "because they don't know how to weld. Working with weird found objects demands a skill. " The metal's difficulty is part of its appeal for Clear. She's been able to carve out her own creative niche. She also likes working with metal pieces that once had utility — a dynamic quality she couldn't create on her own. Clear points to more wheelbarrows, the material she used for the heads and the ears of her circus elephants. An old wheelbarrow, she says, is "painted, has lived a long time, and its surface has changed. It was one thing. Now it's something else. " In other words, it has history. Clear also enjoys the physical process of metal working, which she compares to running and crocheting. "Just like running, if you're doing something with your body, thoughts just fall into place. That kind of activity allows things to settle. " Plus, she simply likes found metal found objects, like wheelbarrows. "Wheelbarrows are cool! " she enthuses. After accidentally becoming an art major at UVM ("One thing led to another, and whoops! I'm an art major! "), Clear more deliberately pursued the art of metal sculpture. While other art majors were doing semesters abroad in places such as Italy, Clear enrolled for a summer at the California College of Arts and Crafts in Oakland, so she could learn to weld in a sculptural art environment. After graduation and a few years of waitressing, Clear was ready to get serious about her metal art. To do so, she approached Burlington metal sculptor Bill Heise, and offered to provide help in exchange for studio space, use of his tools, and the opportunity to learn. Though Heise initially brushed off her offer proposal, a year later he offered her a valuable opportunity. |

||

Heise was going out of the country for a few months, and asked Clear to take care of the shop while he was gone. He also told her, "I better see some work when I come back. " She thought, "Uh-oh, I better get to work here! " It was just the right kick in the pants for her. When Heise returned, Clear had a full body of work. And, she'd gotten into her first art show with a women's group in downtown Burlington. She was on her way. Later, Clear moved to share studio space with Kate Pond, another metal sculptor, who remains a mentor and friend (Heise passed away last year). She grew as an artist, and her work did too. In the beginning, Clear didn't want to create anything she couldn't lift by herself. Space was an issue in Heise's studio, where she had the spatial equivalent of one car. The move to Pond's studio gave her the space, and Pond, who was making work that had to be lifted by heavy machinery, taught Clear how to make big pieces. Thematically, Clear's work has also evolved — from figurative pieces like "Can Can Girls, " where the challenge was "how to make this gnarly material pretty and girly, " to her current "gritty and glittery" circus themes. She does public sculptures and private commissions. Like Janet MacLeod, Kat Clear says she's "not ever concerned with the sculptural market. " She just makes what she wants to make. Her website shows the wide range of themes—and sizes—in her creations: www.katherineclear.com Also, like MacLeod, Clear's work is rooted in a sense of place, in Vermont and its "massive agricultural history. " From her experience foraging in the "big, huge piles" where scrap metal is collected to be recycled, Clear observes, "Vermont is sort of removed from a bigger sense of industry. It's unique, smaller, more manageable. " Here she can find a lot of used farm equipment, with paint that has survived through years of hard work — paint and metal that has another life as a Kat Clear sculpture. |

|||

|

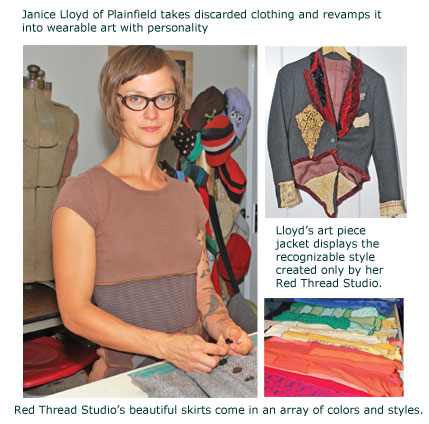

Her Own DrummerJanice Lloyd of Plainfield marches to a different drummer. Unlike MacLeod or Clear, Lloyd was not an art major in college. She chooses recycled materials for her art as an idealistic and pragmatic commitment to minimizing impacts on the environment, first and foremost. "There are huge mountains of resources we just bury, " she says. "And we're still manufacturing clothing in an unsustainable, unethical way. " |

||

Lloyd is determined to have an ethical business. Beauty is important. And so is keeping fabric out of the waste stream. Lloyd shares some qualities with MacLeod. Her life motto is, "Make do with what you have. " She prefers to trade, borrow, or figure some other way rather than simply buy. Nor does she wish to get sucked into a 9-to-5 job that prevents her savoring the simpler pleasures of life. With sculptor Clear, she shares ambition, the energy of a young, busy life, and the desire to keep trying new things. "I'm one of these people who is all over the place, with lots of ideas, always learning new skills, " Lloyd observes. For instance, she and her partner recently created a new enterprise, named Rock, Paper, Scissors. They learned metal sharpening skills for their business at a seminar in Cleveland, where the focus was on scissors and cooking tools. In Vermont, much of the sharpening demand is for shovels, pruners, gardening tools and tools for farriers and woodworkers. Tool sharpening extends the life of equipment. Thus, like her Red Thread Studio, the new business grew from Lloyd's commitment to relearn skills and get back to basics. "Let's fix and work with what we've got, across the board: clothing, artwork, gardens, soil, " says Lloyd. "We need to regenerate the structure in our deprived soil systems to grow healthy food. " |

|

||

Oh, yes. Lloyd is also a certified permaculture designer. And a painter, who finds many of her acrylics free at yard sales. She gives most of her paintings away. Lloyd happily notes, "My clothes are patchwork. My life is also patchwork. " So were her college years. At Lyndon State she majored in Cultural Studies, sampling diversity: religion, mythology, history, anthropology, philosophy and art. Post-college, Lloyd sought out non-degree programs to learn specific skills that have helped her channel her creative juices. Although Lloyd's mother and sister were highly skilled seamstresses, Lloyd was a tomboy growing up. She says she was too busy climbing trees to learn to sew. But after college, when she researched ways to make a living without working for someone else, she finally started sewing. First came hats, starting with a cloche. "I really like old, antiquey-looking things, " Lloyd says. "I love big, old, ugly plastic buttons. " She created her own style, a modernized 1920s look. She next bought a surger, a special sewing machine made for stretchy, knit fabrics. Red Thread Studio was born. That was five years ago. Red Thread continues to fulfill Lloyd's artistic and philosophical needs. Of non-repurposed clothes, she says, "When you make a decision to purchase, you can ask: Who made it? Where? How were the employees treated? What dyes were used? And, do you want to put that on your body and carry the guilt around? " |

|||

Whereas, of her repurposed clothes, she says, "It makes me so happy, to see people put something on, that can make them feel sexy! I love the connections I make, helping people realize the potential of resources already in existence. " Her work, she says, "goes back into the stream of use, not the stream of waste. " |

|

||

There's one other piece to Lloyd's patchwork life. She loves teaching. In the past Lloyd has taught sewing and reuse crafting at Re: Generation, a summer camp for girls. She loves passing on her skills, and hopes to spend more time teaching at in-school and after-school programs. Creating community and making do, Lloyd anticipates a major shift happening in our values and methods. "Art is a statement about our internal landscape, " she observes. "It's reflected in our environment and culture. We're experiencing a major shift in consciousness, and our art reflects that. Art isn't just about beauty. When you're in need, and you need to create, then you use whatever you've got to create something of beauty. " You can see Lloyd's creations of beauty at www.redthreadstudio.etsy.com |

|||

|

|||

| Ginny Sassaman is a writer, artist, activist, entrepreneur, and mediator. Her most recent venture is opening The Happiness Paradigm Store and Experience in Maple Corner, Vermont. |

|||