|

A woman tourist paces to a makeshift grandstand in a hot, dusty arena in Northern Thailand. It is the first day of a program that pairs Westerners with elephants and their mahouts, or life-long trainers, at an elephant conservation center. She feigns a smile, as other tourists and schoolchildren gawk. Old feelings of exposure and shame lick at her face – her birthmarked face – like cold little flames.

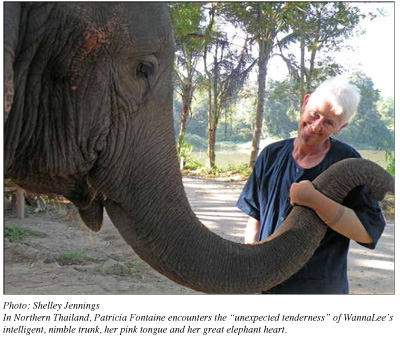

At the edge of the stand, she turns her back. Forty feet away, an elephant named WannaLee picks up the straw hat her mahout has tossed to the ground and carefully walks it toward the standing woman. The announcer chortles, in Thai and English, "Do you think WanneLee can put the hat on her head?"

With a great soft exhale, the elephant gently lowers the hat. The woman bows in staged gratitude and as they walk out, WannaLee's trunk tip finds her shoulder.

There may be applause, but the woman is concentrating on the feel of the warm, weighted trunk, on dissolving shame, tasting its familiar complexities, sensing the size of the birthmark resume its place, from a swollen distortion to a flush, flattened landscape.

After the show, the elephants amble to the grandstand for bananas and sugarcane, shyly offered by jostling children and camera-rich tourists. Now astride WannaLee, the woman again readies for stares. Yet no one looks at the human riders. They only have eyes for the animal's vast pink tongue, ultra-long lashes, nimble trunk reaching for more.

As the elephants file out, sun catches the delicate edge of PanKhot's flapping ears, the elephant just ahead. Rather than slate gray, the rims of her ears are rosy hued, and the light shining through them is unutterably lovely.

Why is this color on an elephant, so close to the color of the woman's birthmark, automatically beautiful? And why is this color on a human face so tinged with questions of otherness and distortion?

The tourist woman is me, and this is the most recent of many stories about life with a birthmark. Here is some of the terrain of what it means to be physically distinct, visible and invisible, and some of the ways I've learned to inhabit this facial landscape as is.

|

|

One of the perks of having a distinctively birthmarked face, in my case a Port Wine Stain, is that people remember me. Couple that with living in Vermont, in towns and communities that keep their bank tellers and post-office workers, and it makes for a nice sense of home.

On the other hand, I get called "Sir." A lot. Perhaps people see the birthmark which runs in purplish maroon from my right ear, spills down cheek to neck, and splashes across my chin—as a beard. But being called "Sir," seated in a red Mustang convertible at a gas station that long ago time in Key West while wearing a bikini…?

The recurrent comments don't stop with "Sir." Here are a few samples:

-

Small boy in post office shrieked when he saw me. His mother quietly noted that some people look different than others. He wailed, "But I don't like the different!!!"

-

Cheery woman in department store elevator loudly pronounced, "Oh, you've been kissed by an angel!"

-

Client at mental health clinic, scrunched far away at our first meeting. He confessed he was worried he'd "catch it."

-

Madeup woman behind makeup counter bustled around it to tell me she had make-up that would "help."

Irish elder in tiny town of Ardara inquired, "Are you alright then?" His baby granddaughter had 'the marks' and her parents were desperate to remove them.

-

Orange-aproned customer rep in the plumbing aisle tapped me on the shoulder: Had I ever tried laser treatments?

I am perceived as distinct enough that it catches some off-guard, jostles a response, a need to mark their reaction by offering pity, or intervention, or simply the wish they'd be gone. The underbelly here is the jerk of compulsion – to jump the fence of personal space, to insist people like me conform to an invisible norm.

The norm of looking good, right, and whole. The norm of beauty.

Notice I've used the word "distinct" rather than "different," thanks to conversations with UVM Psychology professor and friend Sondra Solomon, who has done significant research on the nature of physical difference, especially for women of color. She coined "physical distinction" to counteract "different," (or the other "D" words commonly used to refer to us: deformed, distorted, disfigured, defective, deviant…) and therefore, in the eyes and hearts of many, "other." Beauty aliens. |

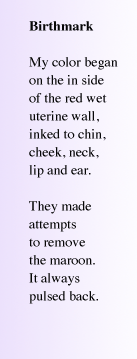

For much of my life, despite deep friendships and successes as a teacher and writer, I have embodied this sense of 'other.' It is lodged deep in the skin color I carry. Reinforced by terribly painful and unsuccessful medical treatments as a child: tattooed with flesh colored ink; cauterized; frozen; my skin grafted. There were the weekly, often daily, reactions of strangers; and the incessant bombardment of "normative" beauty.

I have always resisted covering up. I hated the thick theatrical makeup resolutely applied by my mother for each school morning or family event. Years later I chose not to reconstruct my breasts lost to cancer; or wear wigs to hide a chemo-bald and exquisitely sensitive head. Resistant, yes, but isolated.

Isolation was often a refuge. A lucky stumble into feminism in my mid-twenties helped rescue memories. Astonished by the universality of women's objectification, I was able ask this question: Were there others like me?

Thirty years after that question, I finally immersed myself in graduate work, the study of birthmarks. What I'd kept at bay was an unconscious, internalized notion that it would be difficult to see others with this face. Yet I've yearned to find "my people," often approaching strangers with visible birthmarks to compare notes. Most were polite, but like skittish horses, they soon showed the whites of their eyes and made excuses to exit.

Memoirs of birthmarked and "facially deformed" women preferred or perhaps felt pressured to disappear behind makeup or surgery. Websites were much the same—advertising fronts for reconstructive surgery or cosmetics. Everything I researched that had to do with facial difference termed itself by mainstream norms, of how one is supposed to feel, look, and live. And of what one is not in relation to what is presumed normal— the normal of "beautiful." |

|

This litany of defect and reconstruction wore me down like coarse grit sandpaper, the kind that will take your skin off. None of what I read spoke to the mystery of my resistance to makeup and surgery, a resistance that began in my teens. I wished for a truer destination, one that didn't demand removal or disappearance. I wanted a place for my experience of a different face, like the geography Linda Hogan introduces so eloquently in The Woman Who Watches over the World:

…to know the private landscape inside a human spirit...It's not that we have lost the old ways and intelligences, but that we are lost from them. They are always here, patient, waiting, for our return to their beauty, their integrity, their reverence for life. Until we do, we will have restless spirits. |

What is the landscape of beauty? For me, it is always remote, and always nearby. My mother, a beautiful woman, often told me I was beautiful yet engineered a childhood of treatments to get rid of my marks. It took 20 years of teaching a course called "Mothers and Daughters" at UVM to understand that paradox, to see how the woman who called me an "American Beauty Rose" would send clippings of treatments well past my request that she stop.

Like so many post-war brides, my mother learned to critically measure her own worth on looking good: beauty parlor, endless diets, a facelift at 65. I believe she truly thought that the currency of beauty, refused by me, would doom her daughter to spinsterhood.

Late in life, her accrued bitterness about an aging body stunned me. Shortly before she died, I helped her shower, gently toweling off the tender skin over the pearls of her backbone. She hissed, "This is what you'll inherit." When I told her I loved her body, her look was withering. "Please," she said. "Don't."

Nearby. Remote. Whenever I enter places where people react, my birthmark carries a paradox of visibility and invisibility. My whole self is sometimes condensed to "that woman with the birthmark." Yet people often tell me they don't see it, and truthfully, sometimes I forget – until I look in the mirror.

My color alone is quite remarkable – a rich maroon with gradations of red and violet. But compared to standard beauties with clear, luminous faces, I could never see myself as lovely. Friends do, my sisters do. But could I find my own way to beautiful?

|

|

When I started to research the culture and history of beauty and birthmarks, I was unprepared for the emotional impact. I stared in anguish at pictures of children and adults with birthmarks in medical texts and gathered evidence of appearance norms gone increasingly destructive to women's bodies. The paradox was bewildering – those with birthmarks were considered unbeautiful. Those who altered their bodies were considered beauties.

In 1995, when I had to alter the landscape of my body to cancer, I went out of my way to visit an eminent woman surgeon. As she hefted my DD breast in her hands, she appraised its weight. "There is plenty here to work with," she said, smiling amiably.

I was puzzled. Work with how? She went on to say that of course I would want reconstruction. To make my husband more comfortable. To be more feminine.

My partner at the time, a woman right there in the room, gaped, and I gaped. Outrage and betrayal took turns firing off rounds in my belly, in my heart. I gathered back my breast, soon to be gone, and wished I'd had enough dignity to ask that she never again make such an assumption.

Beauty = amend/correct/improve.

This is imbedded in us, as author Phoebe Hyde noted in a recent radio interview. Imbedded as in viral, as in virulent, where makeup or "cosmetic" surgery is used to correct that which is unacceptable. (A fellow resister, Hyde published this year The Beauty Experiment: How I Skipped Lipstick, Ditched Fashion, Faced the World without Concealer…and Made Over My Life.)

Who selects the standards?

|

|

I began to track animals with a local conservation group. One of the trackers showed me an essay about the nature of seeing, rather than looking: how successful tracking of animals is more about opening our senses to the landscape—the shape of trees, temperature of wind, texture of terrain—than of following a linear paw print.

As I learned to listen and see more carefully, something shifted about the nature of beauty. In the sifted light of an oak and white pine forest along the banks of the La Platte River, beauty revealed itself not as appearance, but something else, something quite incapable of being made or bought. Something that sensed me, as much as I felt it.

This was part of my bridge to a new geography. To enter that space, I began to consider how I might use writing and imagery to get at finding beauty in this more reciprocal way, and develop workshops that would help people like me, who struggle with feeling different, to locate a truer sense of beauty.

It seemed that one way to make beauty more user-friendly would be to reconnect with the loveliness of nature, return it to our bodies, utilize that knowing to resist the norms—and engage self-acceptance of our beauty, as is.

As is.

This has morphed into the work I now do: teaching a Healing Art and Writing class for folks dealing with illness and their caregivers. Just this morning, we looked out the window at Hope Lodge, and imagined that wintry beauty in us, nourishing the creative impulse to write or draw whatever it was that asked for healing, wherever it might dwell in the good and patient body. |

|

Remembering how healing it had been to write poems to meet and decipher my years with cancer, I next began to write a memoir. As I sifted through memories of being a kid, teen, young adult and middle-ager, my birthmark changed. It did not change color, shape, or where it lay literally on my skin. It changed figurative place, becoming less the huge thing that preceded me in the world.

Surprised in a new way by how much my birthmark has shaped who I am, I came to know my color more honestly and intimately. My written snapshots unpredictably bridged me into an inner geography that fit. It brought my birthmark back home, flush on my face, and brought the self I had extended to front my unacceptability back into my arms.

Here's the surprise. An unexpected tenderness. Like realizing that I really could straddle an elephant in Thailand and absorb through my hip bones her intelligence of movement and deep rumbly language to the others of her kind.

Something in me had altered. I see more of myself in you, and you in me, than I was capable of from the isolation of difference.

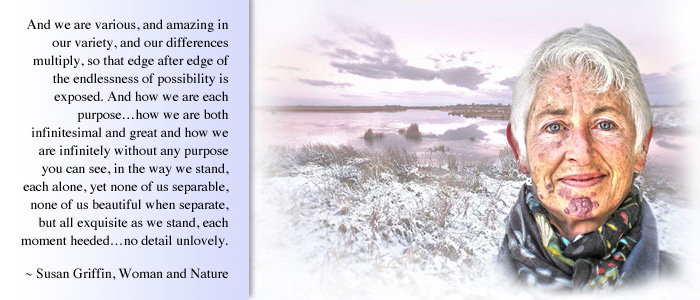

The geography that surrounds us, no matter what we look like, is a shared one. Perhaps we each know, in our tree hearts, in our elephant hearts, how "we are both infinitesimal and great …none of us beautiful when separate, but all exquisite as we stand, each moment heeded…no detail unlovely." |

|

|

|

Patricia Fontaine lives and writes in Shelburne. She has been a teacher and workshop facilitator for many years. After numerous adventures in healing, she is particularly interested in art and writing as refuge.

Patricia currently teaches an expressive art and writing class in Burlington and Central Vermont for anyone dealing with illness and their caregivers. She self-published a book of cancer poems, Lifting My Shirt.

|

|

|