| Barbara Zucker – Sculptor on the Edges of Time | |

| by Suzanne Gillis | |

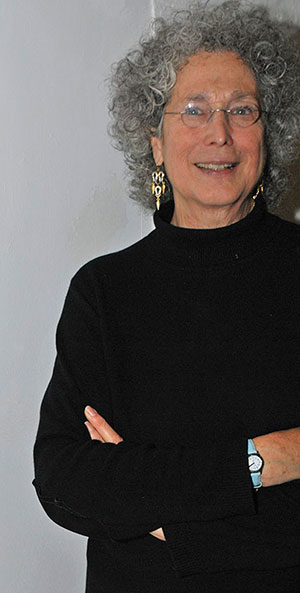

Vermont Woman was recently invited for a private tour and conversation with Burlington sculptor Barbara Zucker. The massive scale of Zucker’s private studio provides the physical work space that she requires to conceptualize, create and produce individual sculptures or a whole series of sculptures as she has done most recently. These grow from her self-realization as a woman, and it is clear she is an artist who lives with fierce sensitivity, intensity and awareness of a cultural landscape that both idolizes and victimizes femininity. Barbara Zucker is a graduate of the University of Michigan and has an M. A. in sculpture from Hunter College. She is one of the founders of A. I.R Gallery in New York City, the first all-female cooperative women’s art gallery in the U. S., begun in 1972. Zucker’s work has been widely exhibited, including in solo shows at Robert Miller Gallery, Artists Space, Sculpture Center, Tufts University, Pam Adler Gallery, Moore College of Art and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Her work is also placed in collections at the Whitney Museum, the Brooklyn Museum, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Hebrew Union College Museum and others. She has taught at the University of the Arts in Philadelphia, Princeton, Yale, the Vermont Studio, Boston Museum of Fine Arts and Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in Maine. Zucker chaired the art department at the University of Vermont from 1979 - 1985. She is now a professor emerita. In her latest artist’s statement in October of this year, Zucker writes: “I have been making sculpture since I was 19, and was sure it was what I wanted to do when I finished art school. I’ve spent over 50 years translating the thoughts in my mind into three dimensions, sometimes with success, other times with flops that hit the garbage can. Sculpture–looking at it, making it, talking about it, thinking about it–is woven into my existence. “I don’t overanalyze it. Like many close relationships, it just is. I am mistrustful of artists’ statements, including my own: often they are pretentious or filled with gobbledygook: the art must speak by itself. Listening to what an artist says may be interesting, but it isn’t always enlightening. With that caveat, I offer a few more thoughts: starting a new body of work is always frightening and thrilling. When I first get an idea and think I know how to make it work, I’m high; then the process starts to be very close to drudgery: doubt creeps in and I remind myself once again: I’m in it for the long haul.”

|

|

Time Signatures: Front of My Neck - In steel

Time Signatures: Cyro - In "radiant" acrylic

Time Signatures: Standing Smile: Judy - In aluminum |

|

|

Zucker began her sculpture series, For Beauty’s Sake, in 1989 and worked on it until 1997. This series, which includes 26 sculptures, developed early on as a humorous response to the soaring plastic surgery business just beginning to rage. The work is composed of before-surgery and after-surgery representations of liposuction, leg shaving, buttocks lift and breast enhancement. Amy Schelgel, then a Curatorial Fellow at the Hood Museum of Art, said about the series in Sculpture Magazine (1997), “In its formal brevity, which is the soul of wit, lies the crux of Zucker’s success: her ability to make viewers–-both male and female–chuckle at their own foibles, while also recognizing their voluntary and unwitting complicity in the beauty myth. This type of discomforting, ambivalent response is also a fundamental acknowledgment of how our body comes to be gendered–as the accumulation of its experiences as a social, sexual, psychological, and material construct. Humor, for Zucker, is also a catalyst with which the double-edged scalpel of gender roles is played out, in which women are simultaneously empowered when they meet the cultural ideal of femininity, and yet are made vulnerable (and even victimized) when they become sexually objectified by that ideal. ” Zucker later said, “At some point after finishing the series in 1997, it all stopped being funny. It became deadly. Deadly depressing.” Her work on a new series began in 1999 and evolved from her work in For Beauty’s Sake. Zucker said she began to confront her own aging process. She worked on her Time Signatures series until 2012. She came to believe that facial and neck wrinkles on the female face were not ugly, as our culture tells us. The same culture that says men’s craggy faces are distinguished also insists loudly and publicaly that women erase, pump up, tighten up, Botox, peel and wax theirs. In other words, our culture encourages women to hate what they naturally look like. Zucker became enraged by this realization and was inspired to create a large number of sculptures formed through a process of mapping the patterns of wrinkles in photographs of women’s faces and necks. Zucker began by photographing her own neck and face. Other faces she used were those of Golda Meir, Rosa Parks, Georgia O’Keefe, Louise Bourgeois, Lucy R. Lippard and Linda Nochlin, a collection of women widely respected for their work. Then why not respect their wrinkles, too? She refashioned the lines and patterns from their faces in steel and rubber, and then finally used a special plastic, which has in it the characteristic of reflecting light in rainbow color prisms. The patterns are revealed as beautiful flowing, moving shapes. With the wry candor she is known for, Zucker says of her Time Signatures series, “I would like women to feel better about the complex, amazing maps of their faces. But equally I want to flay my skin and rail against the ravages of time. ”

|

|

Suzanne Gillis is publisher of Vermont Woman and an ardent art enthusiast.

|

|