| Changing the Men Who Batter | |||

| by Kate Mueller | |||

|

|||

| Meg Kuhner, codirector of Circle, a nonprofit in Barre that provides services to domestic violence victims, did just that for 10 years. From 2004 to 2014, Kuhner worked closely with men who batter as a community facilitator in IDAP (Intensive Domestic Abuse Program), an intervention program for batterers. The program, which ended in 2014, was created and supervised by Spectrum Youth and Family Services in Burlington under VIP (Violence Intervention and Prevention). It ran, said Kuhner, for about 15 years, with programs in Barre, Burlington, St. Johnsbury, Bennington, and White River Junction to name a few. Kuhner said she did this work “full of heart and passion,” her passion rooted in a conviction that all people can change, and she did witness big transformations. “I saw a tremendous amount of change,” she said.

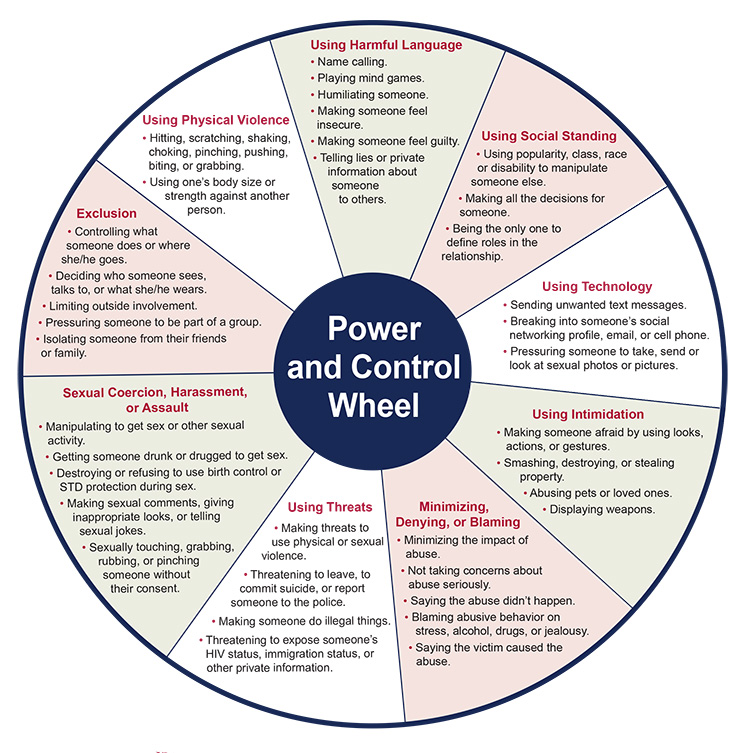

Kuhner said that all the men she worked with were very well aware of their intentions. “They were clear as a bell about why they were engaging in the abuse,” she said. “One stated, ‘Abuse is the key to getting my own needs met.’” Victims, said Kuhner, have a “hard time wrapping their heads around” this fact: that the tactics abusers use are deliberate—that the men they love are consciously manipulating them. Kuhner discussed some of the common traits of abusers. For one, they are usually extremely possessive. “They are incredibly jealous and possessive. They can’t tolerate their wives or girlfriends talking to or even looking at another man,” she said. They are egocentric and take everything personally, said Kuhner; everything is a personal assault. But though they are hypersensitive about their own boundaries, they have no sense of another’s boundaries, particularly family members. But beyond the family is the broader patriarchal society, which, says Kuhner, supports hypermasculinity, validating the men’s sense of male entitlement. “They feel entitled to be head of the household,” she said. “They assign gender roles. The woman is a possession and seen as less than fully human.”

The challenge for Kuhner and her coworkers in the program was to reframe the whole belief system of these men. To accomplish this, the men met in groups of six to 10, twice a week, for at least 13 months. The groups were facilitated by two people, one man and one woman: one person would be from the Department of Corrections; the other from the community. There were many groups throughout the state; Kuhner worked in one of three in Barre. Some of the men were in their 40s and 50s, but most, said Kuhner, were in their 20s and 30s, and for the most part they were lower income. Kuhner sees their socioeconomic status less as an indicator of the men who are likely to batter and more the result of these men being unable to afford a good defense attorney. The men, who ranged from felon-level batterers to multiple misdemeanor DV offenders, were offered the opportunity to decrease their time in prison by agreeing to participate in the program. The teams used a number of exercises, key among them was role playing. The men were taught how to treat women as equals and have a respectful dialogue with a female partner: lacking a role model for this growing up, they didn't know what it meant to be in a good relationship. The facilitators would also ask the men a series of questions that encouraged them to examine their lives and become more self-aware. The men would be asked to identify a time when they were violent. They would be asked what sparked the abuse, what they did that was abusive, what they were thinking and feeling at the time, and what they had hoped to achieve with that action, what their intentions were. And they would be asked what beliefs they held that made it OK to engage in this behavior. Having male and female cofacilitators provided an example to the men that, over time, made an impression on them, said Kuhner: “They would see my male cofacilitator being very respectful to me and also to them. They had never been in a group with a real intention of respect.” The men typically conflated respect and fear and believed that respect was not possible without instilling fear in others. Most of the men saw themselves as good dads or wanted to be a good dad or, at least, be seen as one. This desire provided another opportunity for change. The cofacilitators would ask the men to identify the characteristics of a good father: such as caring, tender, emotionally open, responsive, flexible, reliable—and, yes, loving and affectionate to the mother. They would then ask the men to list the characteristics of an abuser: controlling, poor communication skills, blaming others, possessive, intolerant. Just that exercise alone could be transformational, said Kuhner, when the men realized that there was no overlap between these two ways of being: as abusers they could not be good dads too. Helping the men find internal motivations such as these for change was key, said Kuhner. Simply being enrolled in the program to avoid jail—an external motivation—wasn’t sufficient for lasting change. Kuhner says it’s unfortunate that this particular program ended. Intervention programs do exist in the state for batterers. These programs are overseen by the Vermont Council on Domestic Violence. The council, which is mandated by the legislature to provide leadership in the state’s effort to eradicate domestic violence, was originally created by Gov. Howard Dean in 1993. But the time in treatment is far shorter in current programs, with groups meeting once a week for six months, which Kuhner feels is not sufficient time to change behavior.

|

|||

|

Kate Mueller, editor of Vermont Woman newspaper, lives in Montpelier.

|

||