| Sabra Field and Julia Alvarez: Two Creative Vermonters Collaborate | |||||||||

| by Cynthia Close | |||||||||

Vermont has been a fertile place of inspiration for many artists and writers, but few have embraced it as significantly as printmaker Sabra Field. The green mountains, fecund valleys, dirt roads, deep lakes, and meandering streams have all been subject matter and were clearly on display during the artist's recent retrospective of her last 60 years of image making, held at her alma mater, Middlebury College. The exhibition, which closed on August 13, 2017, was the 82-year-old Field's third retrospective, honoring her long, productive career. Called Now and Then, this exhibition was perhaps Field's most personal and revealing to date, based on the anecdotal notations beside each work, which place the images within a memoir-like context. The sheer decorative beauty of the prints at times belies a darker motivation behind the subject matter. An early 1965 self-portrait bore the caption: "This is me the year I grew up, age 30, when my parents died within a week of each other." Surely, making art helped the artist through a year when her mother died of a heart attack and her father committed suicide. This was enough tragedy for any one life; however, it was not the last tragedy that would affect the tone of Field's imagery. In 1971, her firstborn son, 9-year-old Clay, died after an automobile accident. The following year, her contemplative suite of 14 prints of text images for the 23rd Psalm was exhibited at the Stratton Arts Festival and marked a beginning of her focus on landscape. |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

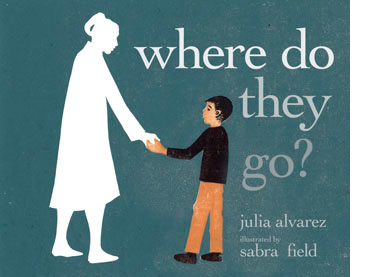

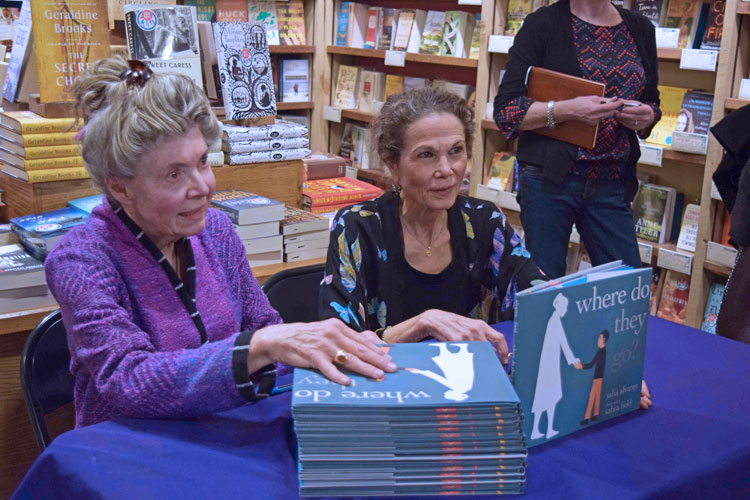

Given the emotional range of Field's work and the dark back story to some of her images, it is not surprising that she collaborated with writer Julia Alvarez on the illustrated children's book dealing with death titled Where Do They Go? (published November 2016). Julia Alvarez and Sabra Field, two mature artists at the peak of their respective careers, recognize the necessity of working alone in their studios to process the complex thoughts and dissect the emotions that undergird their best work. Yet, there are times when it takes collaboration to realize a vision. In the case of Where Do They Go?, the impetus to collaborate came from Alvarez and the motivation was grief. |

|||||||||

Julia Alverez at home in Vermont (photo: Bill Eichner) |

|||||||||

Alvarez was born in New York City and is often referenced as a Dominican American writer, having been raised in the Dominican Republic until age 10. She is a prolific author of poetry, fiction, and nonfiction and is as respected and credentialed in the literary world as Field is in visual arts, perhaps best known for her 1991 novel How the García Girls Lost Their Accent, which won the Pen Oakland/Josephine Miles Award and Notable Book awards from the American Library Association and The New York Times Book Review. A few years ago Alvarez lost both parents to Alzheimer's within five months of each other. It was a deep loss but not unexpected. Later, when her older sister committed suicide, the loss was of a different magnitude. That's when nearly overwhelming grief set in, and Alvarez turned to reading poetry and short poetic novels for solace: "I must have read every translation of Gilgamesh, the oldest surviving work of literature; Homeric Hymn to Demeter; I read and reread Rilke's Orpheus, Eurydice, Hermes, T.S. Eliot's Four Quartets; David Ferry's Bewilderment. Poems with gravitas, with the grave in sight, the stone briefly rolled away from the mouth of the poet." While Alvarez was immersing herself in the art of Goya at the Middlebury College Library, she came across The Demeter Suite, a series of prints by Sabra Field depicting the Demeter-Persephone story of mother-daughter love and the terror of kidnapping. Alvarez felt she had found a contemporary living artist who "understood grief in a visceral, palpable way." Meanwhile, Alvarez continued scribbling down her own questions about the meaning of life and death: "When somebody dies where do they go? Who can I ask? Does anyone know?" The questions began to come together as one poem "Where Do They Go?" She also realized she wanted it to be an illustrated book for children—"though I called it a book about death for children of all ages." Perhaps knowing that Field was also a Middlebury College alumna gave Alvarez the courage to contact her. She felt Field was the only artist who could satisfy her vision for the book but she was uncertain whether Field would be receptive. Field read the proposed poem and responded with enthusiasm. She agreed to illustrate the book. Alvarez was relieved as she had no backup plan if Field refused.

Any kind of collaboration, to be successful, requires trust. Collaboration is often a monumental task for artists who have earned their place, carved out in their separate disciplines, based on their independent and unique vision of the world. The art world is littered with the bodies of failed efforts at collaboration that ended in animosity and sometimes even lawsuits. The making of Where Do They Go? is an exemplary project whose success was predicated on the mutual respect and admiration these two artists have for each other's work. Who they were as individuals was almost inconsequential since they were strangers before Alvarez approached Field to apply her visual sensibilities to the words on the page. This brings us back to an earlier premise, that all art, to be good, must be an honest reflection of who that artist is as a human being. We know the person through her work.

Once the book project was complete, the next challenge was to find a publisher. In the case of manuscripts that require illustrations, most publishers prefer to be the matchmakers. It is rare to find a publisher willing to take on a picture book that comes as a packaged deal. It was an easier job for Stuart Bernstein, Alvarez's "guardian agent," then they originally thought. This pairing was so well conceived, they found an open and supportive ear at Seven Stories Press, an indie publisher with a social conscious who agreed to take on the project "as is." The lovely, hardcover result can be purchased in bookstores throughout Vermont, or you can order it online through the Seven Stories Press website.

In 1991, Alvarez earned tenure at Middlebury College. For years her love of teaching competed with her drive to write. She managed to successfully juggle both until the demands of being a tenured professor intruded too much on her productive, creative life. So she gave up her tenured post at Middlebury. The college was reluctant to let her go, offering her the position of writer-in-residence. She was honored to accept, allowing her to continue advising students, teaching an occasional course, and giving readings. Alvarez states unequivocally that her experience at Middlebury College is one of the primary reasons she is in Vermont. She says "I've now spent more years at this place than I have anywhere else on this planet. It truly is my alma mater, the mother of my soul." These are potent, heartfelt words.

Even when traveling far from home, as Field was last year in Sicily, she carries Vermont in her heart. While admiring the Italian landscape, Field found herself homesick for Vermont and painted a watercolor from memory. When she returned to her studio here, she converted that watercolor into one of her signature woodblock prints, realizing in the process that the scene was the White River Valley, which she frequently sees as she travels from South Royalton to East Barnard. Titled Cloud Way, this charming print of an intense blue sky filled with puffy white clouds reflected in the winding river below, became the signature print of her retrospective at Middlebury.

At Field's retrospective, the seasonal round of landscape images on display acted as a metaphor for the emotional ebb and flow of life, as Field moved us from the fresh promise of spring grass to the full color of a joy-fueled summer, bleeding into the rich sensuality of a New England fall. But it was the spare images of winter that most spoke to this viewer. They whisper sadness, a quiet calm of death, where I see the strong influence of Japanese printmaker Hokusai, particularly in the 1992 prints titled Flurries I and Flurries II. For those who missed the exhibit, you can see many of these works on Field's informative website. The year 2016 was an incredibly productive, successful time for Alvarez and Field. Julia Alvarez has since returned to writing a new novel Fluency, and Sabra Field continues work on a mural and a stained-glass window. Field finds herself more closely tied to Vermont, saying she "had no plans to ever leave. I'll be buried in the East Barnard cemetery." Alvarez "more and more feels like a citizen of the world." Perhaps they will meet again and collaborate in a future time and place accompanied "by the wind, the rain, the flamingoes, the stars, the bits and pieces of all those (they've) loved and lost."

|

|||||||||

|

Cynthia Close is a contributing editor for Documentary Magazine, art editor for the literary journal Mud Season Review, and an adviser to the Vermont International Film Festival. She lives in Burlington, Vermont.

|

||||||||