| How Stowe’s Women Saved The Helen Day Art Center | |

| by Cynthia Close | |

|

On Stowe’s Main Street, Claire Ashley’s 18-foot tall, inflated, spray painted sculpture, “limppunklovejunk” fairly leaps off the front of the Helen Day Art Center, eliciting giggles and double takes. It hooks passersby, inviting them to come in, grab a map, and discover what lies within the seemingly tranquil village of Stowe, Vermont. This year’s show marks the 23rd year of Exposed, an annual exhibition of sculpture sprawling beyond the confines of the art center’s walls, confronting the viewer, demanding one’s gaze, interrupting routine. Coordinated by curator Rachel Moore and extending from July into October, Exposed, like any event of this scale, could not exist without the enthusiastic support of town officials, the engagement of the community, and the commitment of working artists. But this backing and popularity did not happen overnight. In fact it is the end result of a near epic struggle, when the honorable selectmen of Stowe were poised to tear down the original 1861 Greek Revival building that now houses the town’s vibrant library and thriving art center. Resistance to tearing it down began in the 1970s. But to understand how the Helen Day Art Center got its name and became what it is today, one has to go back even further, to 1955. It was the vision of long-time Stowe resident, Dr. Marguerite E. Lichtenthaeler, who persuaded her patient, friend and companion, Helen Day Montanari, to leave in her will a trust of $40,000 for “the establishment of a Library and Art Center for the town of Stowe.” In today’s dollars that bequest was worth over $349,000, a healthy sum. |

As Beverly Wood, one of the original board members of Historic Stowe, Inc. stated in a 2007 presentation to the then-Board of the Center, “the wording of that trust is what created The Helen Day Art Center.” Those three little words “and Art Center” created a “fiduciary responsibility for the selectmen and for Historic Stowe” to not only accommodate the needs of the library, but to expand the vision to include a working art center in the middle of the town. Yet it would take 26 years to establish Helen Day Montanari’s wishes and finally open Stowe’s art center in 1981. For decades, the original building, referred to affectionately as “Old Yeller,” had served as the town’s high school. By 1973 the building had become inadequate. A new high school was built far outside of town, and the aging structure was abandoned. The survival of this handsome building was in doubt. In the 1970s, there was little respect for buildings of historical significance. The word “preservation” never entered the minds of the town fathers, which was not unique to Stowe. Across the country, vast tracts of homes, churches, schools and libraries were demolished, only to be paved over with asphalt parking lots and newly built suburban malls. The predominant mantra of the time was to tear down the old, and build new. Unfortunately that “new” produced some of the ugliest architecture this country has ever seen, and we live with that built memory every day. But fortunately Vermont, due in part to its mountainous landscape, escaped the most egregious affronts and the wholesale “mallification” visited upon much of Middle America. Still, back in Stowe in 1973, entrenched selectmen and the all-male power brokers of the time were determined to demolish the former high school, disregarding any historic value inherent in the 1861 structure. Democracy struggled back then, just as it does today, when power and money seem to trump the will of the people. There were five town votes and two special town meetings that all favored restoration and preservation of the town building. In spite of this three selectmen hired Knight Consultants of Burlington to conduct an engineering study which concluded that the building had “no appreciable significance and was unworthy of restoration.” Two women were among those who did not accept this finding and rose to the challenge. Beverly Wood and Anne Lusk, both part of the original founding membership of Historic Stowe, incorporated in 1977. Anne had only recently arrived in Stowe in 1972. She had come up for a ski trip from New York City where she was working in the fashion industry, when she met Charlie Lusk, who became her husband, and she stayed. In 1975 she received her Master’s Degree in Education and Historic Preservation from the University of Vermont. In a recent interview, she agreed with Beverly Wood, saying that, “At the time, old buildings simply were not considered worth saving. Even the Stowe Better Business Bureau was proud of its effort to rid the town of what it considered ‘derelict’ buildings. There was a dominant, jocular male attitude that considered restoration frivolous. As for the selectmen, I don’t think they were malicious, they just didn’t seek consensus, especially from newcomers. And you were a newcomer if your grandmother didn’t die in Vermont!” Anne was definitely an outsider by those standards. Her father was an engineer who built chemical plants, and Anne had spent much of her youth outside the U.S., growing up in Japan, Europe and Morocco, among other places. She studied in Paris at Les Ecoles de la Chambre Syndicale de la Couture Parisienne, where she received a master’s degree in fashion design. Her worldly experience could easily have isolated her from the local community in Stowe, but her tenacity and ability to energize people was recognized by like-minded friends and colleagues, and she soon became a team leader in the drive to save the old high school. |

|

In the light of wide citizen support of the restoration project and for the appropriation of funds for a new feasibility study, a second report by A. Leonard Brown, a Boston engineer and member of the New England Society for the Preservation of Antiquities, was released. His findings dealt a devastating blow to the preservation movement. Brown’s report indicated that the building would not qualify for the National Register of Historic Places. As a result the restoration costs would be prohibitive, since it would then not be eligible to receive state or federal funds. In the meantime, William Pinney, who had been appointed in 1967 as Vermont’s first state historic preservation officer, had reached a different conclusion. He indicated that the building was definitely a candidate for the National Register, based on its age, history, contribution to community development and its “outstanding architecture.” He urged the selectmen to consider an application at the national level. The building would then be protected from demolition or alteration if placed on the listings of the National Register. The selectmen balked. This would thwart their plans for demolition, and as late as July 1977, the selectmen still refused to approve an application to the National Register of Historic Places. |

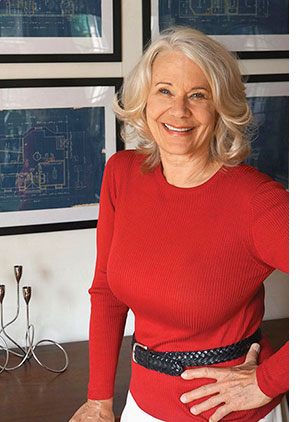

Artist Claire Ashley’s inflated sculpture “limp punk love junk” dances atop the Helen Day Art Center in downtown Stowe. Photo: Jay Ericson |

The selectmen weren’t the only ones who were dubious about the future of the old high school, and how it could be best used to benefit the community. Could it house a much-needed new library? Would it be better used for offices or retail shops, given its central location? Who would maintain it? Meanwhile, the folks who controlled the Helen Day Montanari Trust felt their funds might be better used on new construction. And the Stowe Library commissioners were also hesitant to consider moving into a building that needed so much reconstruction to fit their needs. But the central location in the heart of downtown was ideal for a library, and the residents’ desire to save the old school ultimately convinced the Library trustees that they should work together with Historic Stowe to woo the Montanari trustees. Thanks in large part to the persuasiveness of Anne Lusk, the trustees with the funds joined together with preservationists to form the Helen Day Memorial Library and Art Center. While the old high school was ultimately listed on the National Register, that was only the beginning, not the end, of a long, protracted battle waged between Historic Stowe and some selectmen. Over the course of the next three years, heated arguments concerning financing and the building renovation continued, much of it carried out in the local press. Assisted by the University of Vermont’s Historic Preservation Department and driven by the tenacity of Anne Lusk, “Old Yeller” and 123 other buildings in Stowe were placed on the National Register in 1978. Anne’s colleagues, Barbara Baraw and Beverly Wood, also supported her by serving on the board of the newly established Historic Stowe. Wood is quoted again from the 2007 presentation to the board on the history of the Helen Day Art Center, saying in retrospect:

On a gorgeous summer afternoon in 2014, the past antagonisms and even the opening of the Helen Day Memorial Library and Art Center in 1981 seem a long way away. The sky is bright blue with soft drifts of puffy white clouds. Crowds of people, families with kids in tow, crowd the front steps and fill the first floor, as the annual book sale gets under way. Meanwhile, an even larger crowd of art enthusiasts eagerly climb the stairs to the second floor art center where wine and cheese is being served before the Exposed kick off, an event now grown to a community wide celebration of sculpture and poetry located at 24 sites throughout the town. For this year’s event 17 artists and three writers have brought their work to Stowe. The opening included a guided tour by curator Rachel Moore to each piece, easily located on a handy map. Many of the artists, representing a wide range of methods, materials and stylistic approaches, accompanied the tour, commenting on their own work. As if this weren’t enough food for creative thought, a scrumptious progressive dinner was provided by local eateries at various points along the way. Sculpture is traditionally considered a male-dominated medium. In this exhibition 11 of the 20 featured artists are women. While this may not have been a conscious decision on the part of the jury or the curator, it does speak to the growing influence and power of women’s work and the recognition by institutions like the Helen Day Art Center to recognize its quality. Many of the pieces engaged and affected our perception of the surrounding environment. It was fitting that a number of the works, like Monica Herrera’s “Cascabells,” Karolina Kawiaka’s “Fractured Reflections,” Adria Arch & Lizzy Fox’s “Meander,” and Beka Goedde’s “Fictious Force” were placed at various points along the beautifully maintained Stowe Recreation Path. For here we again encounter the legacy of Anne Lusk. It is she who was the catalyst behind the creation of this bike path that has become a national model. It is arguable that few people have had as great an impact on the culture and livability of the town of Stowe as Anne Lusk, but she would be the first to tell you that positive change cannot happen without the work of consensus. It began with the vision of Dr. Marguerite E. Lichtenthaeler and Helen Day Montanari. But it is only through the collective vision and hard work of many dedicated people that Vermont can attain an environment that enriches and nurtures us all, now and into the future.

|

|

Cynthia Close of Burlington is a contributing editor at Documentary Magazine and a regular contributor to Art New England, as well as Vermont Woman.

|

|