| Three Vermont Senior Women Keep Their Art Vibrant | |||

| by Cynthia Close | |||

|

|||

| Women in the arts are bucking the widely accepted belief that creativity is a product of youth, and as we age our energy and our ability to inspire or be inspired dwindles. Madonna, 57, and Meryl Streep, 66, are international stars who have not let aging slow them down. They continue to infuse their work with new ideas that keep audiences enthralled, and painter Georgia O’Keeffe was active until she died at the age of 99.

Vermont has its share of women whose creative energy has kept them actively at work well into their 80s, a time when many of us feel we are lucky to be able to still walk the dog. It didn’t take much digging to discover three amazing women: Alexandra Heller, Claire Van Vliet, and Fay Webern—all with long, productive lives behind them and exciting new opportunities and projects still ahead. |

|||

| Fay Webern: Writer, Storyteller | |||

|

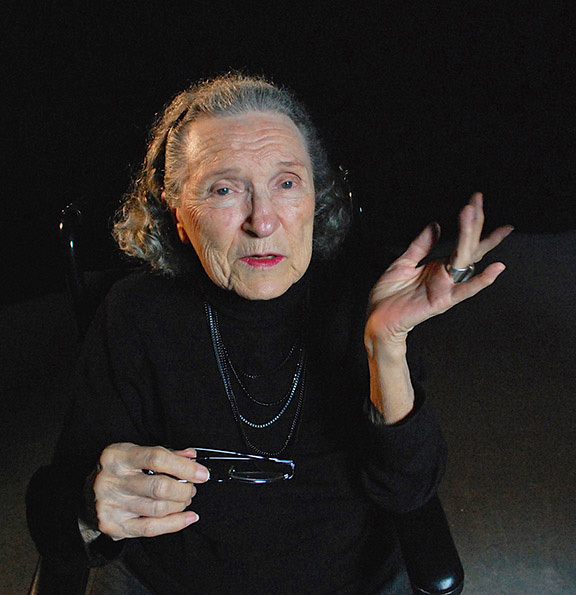

It was a June 2015 press release that initially brought my attention to Fay Webern. The release announced that Webern, 88, would be reading excerpts from her soon-to-be released book The Button Thief of East 14th Street: Scenes from a Life on the Lower East Side 1927–1957 at the Light Club Lamp Shop in Burlington. The accompanying photographs on the release captured the dramatic aura and energy that Webern exudes: her regal, chiseled features and beautifully expressive hands commanded immediate attention. The images suggested that this woman was a natural performer and storyteller, a first impression that was confirmed when I later met her. It was her sly humor that threw me off base when she asked me “How many keys does a piano have?” I hesitated, then she helped me out, saying, with a broad smile, “88.” It was her way of deflecting any questions I might have about her age. Webern was quite enthusiastic upon learning that Vermont Woman newspaper was interested in publishing an article about her, as her own written work gives voice to the strong women who kept her family alive, before, during, and after the Great Depression. She was born in New York City’s Lower East Side in 1927 to Russian-Jewish immigrant parents. The richly detailed stories in Webern’s book run more or less chronologically from her early childhood to the 1950s urban postwar arts scene. She credits her hardworking mother and grandmother for doing whatever they needed to do for the family’s economic survival, from plucking chickens by hand to candling eggs for resale to cutting lace—a job Webern herself did when she came home from school, starting at the age of 7. |

||

The year Webern was born, the fourth child in her struggling, low-income family, her entrepreneurial mother negotiated their move out of their squalid flat on Avenue D into the Lavanburg Homes, the first “utopian” housing community designed specifically for low-income families. It was funded by visionary philanthropist Fred L. Lavanburg, and one of the criteria for living at Lavanburg Homes was that the family must have young children. It was Lavanburg’s goal to have a positive effect on the lives of the next generation by providing a clean, comfortable, collaborative living environment that fostered a sense of community. Webern gives a vivid description of life at Lavanburg in her memoir, which she calls “novelistic nonfiction” rather than “creative nonfiction.” It was while living at Lavanburg Homes that Webern had the opportunity to study dance. Funded in part by President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Work Projects Administration, a dance program was initiated at Lavanburg, and one of the teachers, Hanya Holm, was the first to recognize Webern’s ability as a dancer at the tender age of 7. Holm was one of the founders of modern dance in America. Her approach to teaching “was to liberate each individual to define a technical style of his or her own that should express their inner personality and give freedom to explore.”

At the age of 15, after a tragic accident, Webern lost the ability to dance, but this setback did not deter her from following a creative path in life. She spent most of her adult life working in publishing, first at Scientific American, where she advanced from copy editor to copy chief, and then on to being a senior editor for Encyclopedia Britannica Book of the Year and an editor of college textbooks. She retired in the late 1990s, and while still living in New York City, she studied nonfiction writing with Tyler C. Gore at Gotham Writers Workshop. In Jewish homes you “always kept talk going,” said Webern. Her mother was an expert at telling stories, and clearly that ability has been passed on to Webern. She has contributed over two and a half hours of interviews, recorded as part of the Steven Spielberg–initiated Shoah, a Jewish oral history project. She learned to write in the first person, and soon she was invited to be a regular reader at The Knitting Factory, a popular nightclub located near the World Trade Center. After 9/11, the city became a difficult place for Webern, so in 2002, she moved to Vermont to be closer to her daughter, a professor in neuroscience. In her acknowledgment of the importance of the mother-daughter bond, she strongly suggests, “If you have a boy, try again.” Here in Vermont, Webern has found support for her writing and performances from Montpelier-based agent Peg Tassey. But ultimately it is Webern’s ability as a storyteller that continues to engage and inspire enthusiastic audiences of all ages.

|

|||

Claire Van Vliet: Graphic Artist, Bookmaker, Printer |

|||

| What does an artist do after she has won a MacArthur Grant? That is the once-in-a-lifetime, no-strings-attached award often referred to as the “genius grant,” in part because you have to be exceptional and you can’t apply for it; you have to be selected.

Claire Van Vliet, Vermont graphic artist, printmaker, bookmaker, papermaker, and founder of Janus Press, won the prestigious award when she was 56 in 1989. Some artists would consider this the capstone of their careers, and they’d sit back to enjoy the fruits of their labors. Not so for Van Vliet. She decided it was time to take her work more seriously, that perhaps the award had less to do with her and more to do with the fact that she was blessed with certain gifts, which she has since gone on to develop in the quiet sanctuary of her studio tucked into the idyllic countryside of Newark, Vermont, where she has lived and worked for the past 49 years. Born in 1933 in Ottawa, Canada, Van Vliet attended San Diego State University and Claremont Graduate University, where she graduated with an MFA degree. She founded Janus Press in San Diego in 1955, the year after she left school. |

Claire Van Vliet in her studio. photo: Todd R. Lockwood

|

||

| Her interest in typography and hand-set type was fostered with further study in Europe, and she worked for a time with John Anderson of Lanston Monotype Company, founded in Philadelphia at the end of the 19th century and known for receiving the first patent for a mechanical typesetting device. She also taught drawing and printmaking at the Philadelphia Museum School of Art for a short time in the 1960s, before bringing Janus Press to Vermont.

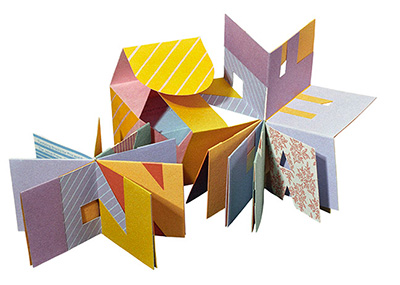

When asked about the naming of Janus Press, she said, “Janus was the ancient god of the rising and setting sun who stood for balance in the Renaissance because of his ability to look both forward and backward . . . the book as a balanced and unified statement with all of its parts integral and serving to illuminate one another is the ideal for which the press seeks.” Schooled in the development of traditional typographic forms, Van Vliet was drawn to exploring the possibilities inherent in book design, considering its value both as a conduit of ideas and its existence as a sculptural object. Her books are at times awe-inspiring feats, requiring great technical skill to both print and assemble. They demand significant amounts of time, sometime years, between the initial idea and the final execution. Such was the case with Greed, a slim volume with a gold paper cover that Van Vliet began in 1973 when she drew and printed four black-and-white lithographs of distorted faces representing a banker, a lobbyist, a newscaster—and John Q. Public, in other words “us.” At the time they didn’t quite fit with the text she had in mind, so they were put aside, only to surface 40 years later, to be combined with the gold paper that had also been tucked away for decades to emerge when the time was right. The finished book was published in 2013 in an edition of 125. |

|||

Most of the books are published in editions of 120 to150, all individually printed, assembled, and bound by Van Vliet and her assistant in her orderly, light-filled studio in Vermont’s rural Northeast Kingdom. She fills standing orders for about 50 customers, which includes collectors, libraries, and museums. Her books and prints are in the permanent collections of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. Van Vliet’s deeply held political convictions infuse much of her work, as is evidenced in the Greed project. She often collaborates on projects with like-minded artists, such as Peter Schumann of Bread and Puppet Theater, another Vermont icon. Her recipe for achieving the best possible solution is “don’t work with authors who are difficult.” She also informed me that “no two projects are alike,” and since she works for herself, she has freedom and flexibility. |

Van Vliet's Tumbling Blocks c. 1996, was made for Janus Press |

||

Van Vliet’s current project, Trio, is a collaboration with three poets, including two Vermonters—Leland Kinsey from Barton and Karen Hesse from Brattleboro. She has several other projects on the backburner as well. While the beauty of the skies, clouds, and mountains and the privacy keeps her rooted in Newark, Van Vliet was enticed to come to Burlington City Arts in June 2015 to accept the coveted Herb Lockwood Prize, which seeks to “reward the pinnacle of arts leadership in Vermont.” The prize comes with a $10,000 stipend, a welcome perquisite. As Van Vliet said, “It is a great honor to be selected for the generous Herb Lockwood Prize, and as any person working in the arts can say about money, it is very welcome and will go toward more work.”

|

|||

| Alexandra Heller: Sculptor | |||

|

The petite, slender, smiling woman standing in the doorway of the Brick House Book Shop in Morristown, Vermont, was a surprise. Having seen Alexandra Heller’s welded steel sculptures both in photographs and now the larger pieces scattered about the grounds of the shop, I anticipated a strong, burly type, capable of producing such powerfully evocative work. When I mentioned this dichotomy, Heller informed me, “The strength is in the flame, rather than the body.” It is her ultimate skill as a welder that is mind-boggling when one confronts the intricate fluidity of works like Plant Form and Flying Lizard, or the simple, rooted-to-the-ground solidity of Three Figures. Born in 1932 in New Haven, Connecticut, Heller grew up in Groton, Massachusetts, where her father was a teacher. Although her parents did not encourage her to pursue a career as an artist, they “allowed” her to move in that direction, as long as she was engaged in learning. Her earliest memory of being turned on to art was at Concord Academy in the fifth grade. A teacher there taught her how to look at sculpture, telling her it had to be interesting from all sides. Later she attended Sarah Lawrence where she thought it would be easier if she became a writer, but her ongoing interest in art eventually brought her to the Boston Museum School, followed by a two-year course of study (1955–1957) at the School of Painting and Sculpture at Columbia University, where she met her husband-to-be, Peter Heller. Being an artist can be hard on personal relationships, and when two artists bond, living together successfully “till death do us part” seems extraordinary, but such was the case with Heller and her husband, who was a painter. When they met during registration at Columbia, she was 23 and he was 26. They remained together, both active in their careers, until he died in 2002, at the age of 73. Right from the beginning, they shared their lives and their work. They also shared an 80-foot-long loft in Manhattan soon after they left art school, which cost them $75 dollars a month. It was divided in half, one side for painting, the other for sculpture. They shared a love of music as well, which provided inspiration for their visual art. |

||

Butterfly Woman Photo: Kip Ross |

While love for each other and devotion to making art kept them together, love and art did not pay the rent, so they frequently had to adapt and be willing to go wherever the jobs were. They wound up in Vermont when Peter was offered a job at UVM teaching French (he had lived as a child in southern France during World War II). That only lasted four years, followed by two more years of Peter teaching French at Bard. A lucky break came in the late 1960s when their friend Robert Babcock, who happened to be provost of Vermont State Colleges at the time, offered both Peter and Alexandra teaching positions in the art department at Johnson State College where they remained until Peter retired in 1984. Heller said it was “magic” that brought them together, but it may also have been a similar way of looking at the world, which is evident in their artwork, on display at the Brick House Bookshop. Though Peter’s paintings are flat and hang on the wall and Alexandra’s work is three-dimensional, appearing to dance in front of his images, both of their artwork shares an undeniable connection to the natural world. While love for each other and devotion to making art kept them together, love and art did not pay the rent, so they frequently had to adapt and be willing to go wherever the jobs were. They wound up in Vermont when Peter was offered a job at UVM teaching French (he had lived as a child in southern France during World War II). That only lasted four years, followed by two more years of Peter teaching French at Bard. A lucky break came in the late 1960s when their friend Robert Babcock, who happened to be provost of Vermont State Colleges at the time, offered both Peter and Alexandra teaching positions in the art department at Johnson State College where they remained until Peter retired in 1984. |

||

| Heller said it was “magic” that brought them together, but it may also have been a similar way of looking at the world, which is evident in their artwork, on display at the Brick House Bookshop. Though Peter’s paintings are flat and hang on the wall and Alexandra’s work is three-dimensional, appearing to dance in front of his images, both of their artwork shares an undeniable connection to the natural world.

Heller still lives and works in the book shop. She started the used bookstore to supplement their income. It is open “by chance or appointment,” but now she says people rarely come to buy books. Instead, it serves more as a gallery space. The first floor is filled with bookcases that double as pedestals for Heller’s sculpture. When asked about the artist who most inspired her, she surprisingly mentioned Henry Moore; she explained, “He was rooted to the ground but I’m reaching for the clouds.” Her rural surroundings feed her love of nature and clearly influence the subject matter of her work. Flower forms, seedpods, turtles, bats, and seahorses twirl on their stands or lunge from the wall. There is a fluidity and spontaneity to her forms that is organic, but her process involves careful planning, study of photographs found in books, and preliminary drawings to determine the scale of the piece before any steel is cut or welded. In her expansive studio on the second floor she has a work-in-progress—initial drawings of a piece whose working title is Conch Shell Woman. She’s also excited about recent experiments in applying color, a burnished patina, to a turtle-shell sculpture. Our last stop is her welding studio, housed in a separate, small building behind the bookstore. We pass a number of large, abstract steel sculptures sitting among the trees, rusting as Cor-Ten does when exposed to the elements. These are earlier works, and Heller is not a fan of the aesthetic rusting process. |

Flying Lizard photo: Kip Ross |

||

Her tools line the walls of the well-organized workshop where her creative ideas are crafted into the evocative forms that fill her home. She has rarely pursued the commercial side of being an artist, which has become a bone of contention with her two children, Stephen and Diane, but now may be the right time. Heller’s work is listed with the Metro Gallery at Burlington City Arts, and with the help of her assistant, photographer Kip Ross, her sculptures, along with her husband’s paintings, maybe viewed on a new website: www.hellerartworks.com.

|

|||

|

|||

|

Cynthia Close writes about the arts for Vermont Woman and several other periodicals and lives in Burlington, Vermont, with Ethel, her St. Bernard–golden retriever “puppy.”

|

||