| Vermont Energy Education Program Gets Women into STEM | |||

| by Sarah Galbraith | |||

Science, technology, engineering, and math—known as STEM—are all around us. It’s nature, weather, and food; our smart phones and computers; our ability to solve modern problems from wastewater treatment to climate change; and everyday equations as we balance our checkbooks, grocery shop, and plan for the future. STEM is vitally important to the future of our children, as well, as these fields offer promising careers with higher pay and tremendous growth potential globally. It’s also the framework that will help the next generation solve problems in our natural and built worlds. An entire contingent of students—that is, girls and women—has been largely missing from STEM programs and careers, historically. Although this is improving, it continues to be the case. Why does this matter? According to a page of the White House’s website on the topic (www.whitehouse.gov/administration/eop/ostp/women), women in STEM jobs earn 33 percent more than those in non-STEM occupations and experience a smaller wage gap relative to men. Plus, girls and women in these fields can contribute to exciting developments and advances for our society—if they show up. The number of women entering STEM degree programs in some of Vermont’s higher education institutions is not an impressive, though. When asked how many women are currently enrolled in Vermont Technical College’s STEM degree programs, like electrical engineering, computer information, and engineering technology, VT Tech president Daniel Smith said, “Not enough.” Out of about 150 students enrolled in bachelor’s degree programs in STEM fields at VT Tech (about 25 percent of the student population), only 14 are women, comprising about 6.5 percent of the overall number of women and only 2 percent of the total numbers of students in bachelor’s programs.

|

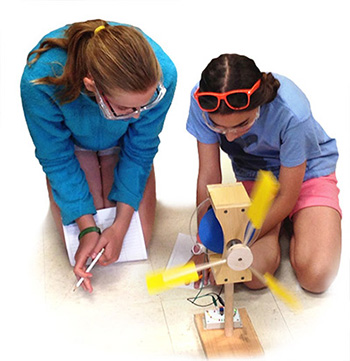

Two girls explore the science and engineering photo: courtesy Vermont Energy Education Program |

||

|

|||

The picture is similarly bleak at the Community College of Vermont, where only 90 students out of about 210 enrolled in associate’s degree programs in STEM are women and only about 6 percent of the total student population are enrolled in STEM programs (including men and women). The state colleges, however, tell a better story: at Castleton University and Johnson State College, about half of the students enrolled in STEM bachelor’s degree programs—like biology, environmental science, and mathematics—are women. Still, the overall numbers of women participating are low, at 55 and 42, respectively.

|

|||

|

|||

|

A shining example of girls and women in STEM in Vermont is the state’s own Vermont Energy Education Program (VEEP, www.veep.org). It’s a nonprofit that brings energy, science, and engineering education to student s across the state with classroom workshops, curricula, and materials and teacher training and support. Since these workshops, curricula, and materials are brought to students in the classroom, rather than students signing up for the program, VEEP educators and materials are getting to the full socioeconomic and gender spectrums.

Interestingly, its nearly all-women staff is modeling women in STEM every day. Five of the six occupied positions at VEEP (a seventh position is currently open) are held by women, including three educators, a director of education and curriculum, a communications coordinator, and the executive director, Cara Robechek. Says Robecheck, “Our educators are doing all of this technical work and engineering tasks with the students, and we’re women. We’re not presenting it that way, but I hope it’s making an impression.” VEEP’s mission is to promote energy literacy—that is, a deep understanding of what energy is and how to use it efficiently in order to enable energy usage choices that will result in a sustainable and vital economy and a healthy environment. In everyday language, Robechek says the goal “is for people to understand energy, and that looks different at different ages.” To accomplish this, VEEP offers several resources, including in-classroom workshops led by the nonprofit’s staff educators. Workshops like “Solar & Wind FUNdamentals,” “Electricity and the Environment,” “Button Up!,” and “Modeling Climate Science” bring hands-on learning to students from kindergarten through 12th grade. The workshops are available for free to all classrooms in Vermont (the first workshop is free and then there is a charge for any additional workshops). Robecheck says in kindergarten and elementary schools, the workshops teach students how energy works in the world. Students begin doing engineering tasks and thinking about these tasks. For middle schoolers, the workshops dig deeper by asking: What does it mean to get energy this way? What are the impacts? At the high school level, the workshops include career exposure by talking about green or energy jobs, especially at career and technical education centers.

The 90-minute workshops cover a variety of energy sources, including fossil fuels and renewable generation, and energy efficiency is an important component as well. “We talk about efficiency as an important step. When you look at the pie chart of where we get our energy, we want to make the pie smaller overall, first,” says Robecheck. To promote this learning, educators’ methods are hands-on and include loads of materials, and they encourage critical thinking at all levels. “We encourage students to look at the pros and cons of each energy source and teach that no energy source is perfect,” says Robecheck. The hands-on lessons, some of which have been written by VEEP educators like Laura MacLachlan, are highly engaging for students. “I have frequently gotten comments back from teachers saying that we succeed with all types of learners,” says MacLachlan. |

|||

|

VEEP educator Erin Malloy says she often sees students in the classrooms she visits make personal connections to the material. Malloy says the workshops are effective because they are live models of STEM teaching practices and they make the content relevant to the students’ lives. A workshop on building solar cookers, for example, is popular as students learn what it takes to make water boil or to cook a hot dog. Malloy says students go home and talk with their families about the solar cookers, and that one student even built one at home with her own mother. “They’re making personal connections that go beyond the classroom,” says Malloy. In addition to in-classroom workshops, VEEP provides curricula for teachers to incorporate in their own classrooms, including the materials to deliver these lessons on energy. VEEP educators provide training to teachers through summer institutes and evening sessions throughout the school year and are available for consultations by phone as well. STEM programs—from lab research to educational programs—require support staff as well, which Dana Dwinell-Yardley provides for VEEP. Although she is the only staff person who doesn’t work in the classroom, she supports the effort by maintaining the website, designing curricula documents, sending newsletters and press releases, writing blogs, maintaining mailing lists and social media, and developing the organization’s annual report. Dwinell-Yardley does not have a science background—hers is in writing and graphic design—and that makes her an important part of the team, since it’s her job to make sure the science is clear to the general public. |

||

Dwinell-Yardley says it’s fascinating for her to learn new things from the other women on VEEP’s staff, like how light works. “And in some ways they get to practice on me. I’m the testing ground. If it doesn’t make sense to me, it probably won’t work for fifth graders, either. I’m enjoying the science education I’m getting as well.” Dwinell-Yardley says working with a mostly female staff at VEEP is a lot of fun. “You should see our staff meetings,” she says. “Six women are geeking out on science together—it’s great!”

|

|||

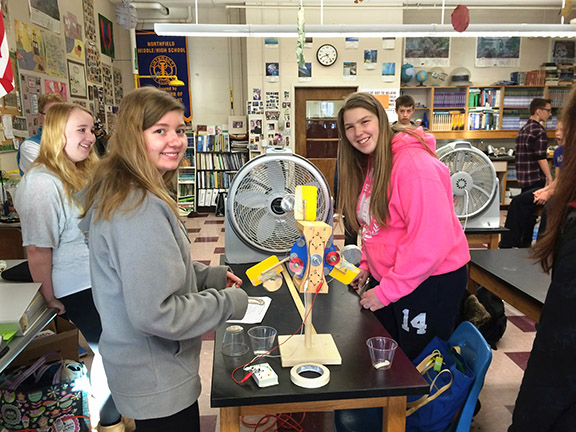

photos: courtesy Vermont Energy Education Program |

Sarah Galbraith is a freelance writer living in Marshfield, Vermont.

|

||