| Wild Women: The History of Women on the Long Trail | |||

| by Sarah Galbraith | |||

View north from the summit of Camel's Humb, which the long Trail passes over.

|

|||

|

|||

We made camp that evening at the Seth Warner Shelter, a three-walled shelter with ample space surrounding it for tent camping. We were about six miles into our hike. That evening, we rinsed our gear and hunkered down in our tent, and thankfully awoke the next morning to dry air and clear skies. Though our gear still smelled like peppermint—and would for the remainder of the trip—it was at least dry, thanks to fast-drying synthetic fabrics. We ate our dehydrated oatmeal breakfast and started to hike and kept hiking until we reached Canada several weeks later. As I plodded along on that trip, the history of the trail was apparent. Several of the shelters are original to the early 1900s when the trail and its infrastructure were being created. Memories of impactful people were everywhere: in the names of the shelters and campsites, in the names of the side trails, and throughout the guidebook that we were carrying to navigate our way. It was the names of women that struck me most. Sure, it was one thing for me to be out backpacking, and I saw every day other women, including backpackers, day hikers, campsite and summit caretakers, and crew members working on the trail. We all benefited from modern gear and a society that accepted us being here. But what about the women who came before? These women pioneers overcame incredibly rough terrain, heavy and antiquated gear, and gender disparity. To me, they were the ultimate adventurers, and I had to know more about them.

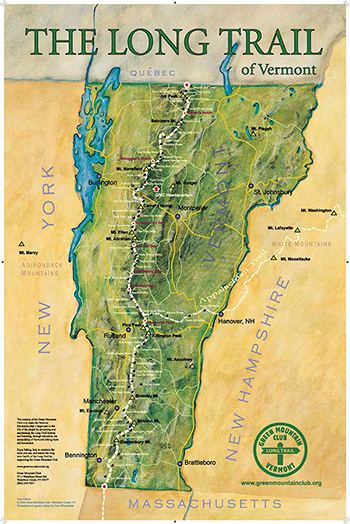

The Long Trail was built by the Green Mountain Club between 1910 and 1930. The 272-mile "footpath in the wilderness" was the vision of James P. Taylor in 1910, to "make the Vermont mountains play a larger part in the life of the people by protecting and maintaining the Long Trail system and fostering, through education, the stewardship of Vermont's hiking trails and mountains." The trail travels the spine of Vermont's Green Mountains from near Williamstown, Massachusetts, to the border with Canada near North Troy, Vermont. Marked by white blazes painted on trees and posts along the way, the Long Trail traverses almost all of the Green Mountains' major summits, including Glastenbury and Stratton Mountains, Killington Peak, Mount Abraham, Mount Ellen, Camel's Hump, Mount Mansfield, and Jay Peak. The Green Mountain Club continues to maintain the trail, decades later, in cooperation with others, such as the Green Mountain National Forest and the State of Vermont. The nonprofit organization's website (www.greenmountainclub.org) provides this accurate description of the trail: "This 'footpath in the wilderness' climbs rugged peaks and passes pristine ponds, alpine sedge, hardwood forests, and swift streams. It is steep in places, muddy in others, and rugged in most."

With their newly earned right to vote and changing societal roles, the "new women" of the 1920s challenged the role of the traditional woman. They enjoyed increased access to electricity, a quickly rising presence on college campuses and in the workforce, and some of the first forms of media and mass advertising directed at them. They cut their hair short, wore makeup, and shortened their skirts. Women were making names for themselves as movie stars, writers, fashion designers, and intellectuals. Out of this time of the Roaring Twenties, jazz music, and flappers, came Hilda M. Kurth and Kathleen M. Norris, of New York, and Catherine E. Robbins, of Vermont, dubbed "the Three Musketeers" when they became the first women end-to-enders on the Long Trail. Norris, 18 at the time, had just graduated from high school, while the other two, both 25 years old, were schoolteachers. They hiked without male companions, garnering them extensive attention in the national news—despite disapproval from some—and helping to put the Long Trail on the map. |

|||

The three set out on July 25, 1927, each carrying 20 to 25 pounds in their packs. Dressed in knee-high boots, knickers, and bandannas, they appear in every image smiling and looking lighthearted and invigorated. But instead of lightweight technical gear, they carried ponchos, blankets, and axes. They mailed food packages ahead to farms along the way to resupply and help keep their pack weight down. James P. Taylor, the founding visionary of the Long Trail, helped spread the word and bring media attention to the women as a way to gain publicity for the trip and promote the trail. The women were frequently met along the way by reporters or photographers, one of whom even brought along a gallon of ice cream that the women ate together on the spot. In 1932, a 12-year-old girl completed the trail with her family, and in 1933, two women again hiked the trail in its entirety. Marion Urie and Lucile Pelsue wore woolen clothes and ate oatmeal, mac and cheese, rice, dried fruit, and chocolate, among other things. They each carried on their belts a knife, a light ax, a canteen, and a pistol. Urie wrote eloquently about their trip in the The Vermonter, where she explained the pistols were for killing porcupines, "or any other pest that sought our company too persistently." In some ways, these early pioneers had an experience very similar to my own on the Long Trail. They endured the same steep climbs, navigated sections of trail rendered impassable by storm blowdowns, and dealt with the same porcupines and mice in the shelters. They also enjoyed the same summits, streams, and forests. But in other marked ways, the women experienced a version of the Long Trail we can never go back to: for one, their views were never spoiled by the 10 ski resorts and countless high-altitude vacation homes that now dot the landscape.

|

|||

|

|||

|

In addition to the women making their way along the trail, many women contributed to the creation and maintenance of the Long Trial. For example, several shelters are named for important women who were active in their local GMC chapters and in the headquarters office, such as the Laura Woodward Shelter north of Jay Peak, the Lula Tye Shelter formerly at Little Rock Pond, and the Minerva Hinchey Shelter south of Clarendon. There are also shelters named for women whose families contributed money to the cause, such as the Emily Proctor Shelter in the Breadloaf Wilderness, Butler Lodge on the north side of Mount Mansfield, and the former Fay Fuller Camp near Bennington. Two side trails connecting to the Long Trail are also named for women: the Laura Cowes Trail on the western side of Mount Mansfield is named for a prominent GMC section leader and outdoorswoman, and the Clara Bow Trail, in Nebraska Notch, is named for the "beautiful but tough" silent film actress Clara Bow. Women dot the time line of the entire history of the Long Trail and Green Mountain Club. Emily Proctor contributed $500 (equivalent to about $10,000 today) for the construction of shelters. In 1916, Joanna Croft was elected president of the Burlington section of the GMC. Katherine Monroe was one of the earliest trail workers in the 1920s, and Edith Easterbrook and Mabel Brownell were the first women on the GMC board of trustees in 1926. In the 1940s, the first end-to-end reports arrived from women hiking the trail alone. In 1969, Shirley Strong became the first woman president of the GMC. In 1973, Wendy Turner and Susan Valyi became the first women caretakers on the trail and were stationed at Taft Lodge. In 1990, Sue Lester became the first woman field supervisor, and from 1990 to 2013, Susan Shea served as the first woman GMC director of conservation. Fast-forward to today, and many women hold the titles of staff, crew member, caretaker, volunteer, trip leader, officer, and thru-hiker. In fact, there are so many that my own thru-hike wouldn't result in a news headline but rather a small listing of my name in the Long Trail News among the roster of 2001 end-to-enders, right alongside many other women. It's a place in the history of the Long Trail in which I'm happy to find myself.

|

|

||

A woman section hiker ascends Mount Mansfield via the Long Trail. Photo: Jocelyn Herbert

|

|||

|

Sarah Galbraith is a freelance writer and avid outdoorswoman living in Marshfield, Vermont.

|

||