| UVM Medical Center Lifts Ban on Elective Abortions | |||||

| by Sally Ballin | |||||

|

|||||

Hallelujah! High time! Long overdue! These were some of the reactions from warriors of the 1970’s struggle for abortion rights in Vermont when news broke that UVM Medical Center (UVMMC) had reversed its long-standing policy against providing elective abortions. Three days after the 45th anniversary of Roe v. Wade, pro-choice Vermonters were happily surprised to learn that the board of directors of the medical center had voted to lift the ban on elective abortions that had been on the books for decades. Many Vermonters may be surprised to learn that Vermont’s flagship teaching hospital has not been providing elective abortions right along, given that abortion has been legal in this state since 1972. In fact, veterans of the abortion rights movement, although they welcomed the news, were surprised by the seemingly sudden policy reversal and wondered what was different now, after all these years, and what prompted the change. Indeed, it is ironic that although Vermont was the second state to legalize abortion, its major hospital in its largest city is only now opening its doors for elective abortions; it has always provided medically necessary abortions for women whose pregnancies have gone wrong. Lucy Leriche, vice president of Public Policy, Vermont, for Planned Parenthood of Northern New England, summed up the general reaction, on the phone recently from the state house: “We’re delighted with the decision. We’re all about increasing access to the full range of reproductive health services. … It’s one more step in helping to remove the stigma in the mind of the public, which is a good thing.” The impetus for this policy change came from the medical staff, according to Allie Stickney, chair of the UVM Medical Center board. Dr. Lauren MacAfee, who has been on the Women’s Services staff for about 18 months and specializes in family planning, stated in an e-mail: “I was one of the physicians who advocated for rescinding the policy. Women should have access to a full range of procedures and services as they make choices with their physicians about their reproductive health. To provide the highest level of care, the UVM Medical Center hired faculty with expertise in this field who wanted to use our expertise to offer women more options.” The board voted unanimously at its September 2017 meeting to rescind the old policy, which said, “Recognizing that there are medically acceptable alternatives, the policy of the Medical Center Hospital of Vermont on abortions continues to be to perform abortions only when medically indicated and with appropriate medical consultation.” In other words, no elective abortions at the hospital because there are other places to get them. Stickney explained: “Across the country, it was not unusual for hospitals to opt out because elective abortions may have been available elsewhere,” as was the case in Burlington, “or to avoid controversy,” which may well have been the case here. However, times have changed: Today’s medical center “must have a full range of services for women, including abortion, in order to provide the best kind of care for women,” she added. What’s more, “as a teaching hospital, doctors must learn to perform abortions because they are a very common procedure—that is, often performed—and doctors should learn in the best possible teaching environment.” Before the policy reversal, medical students had to opt for a rotation at Planned Parenthood to get training in abortion procedures. It was not part of the standard curriculum for students becoming obstetricians and gynecologists. (A hospital spokesperson stated that, in updated policies, hospital staff and physicians may opt out of abortions or any procedure if they wish.) However, the Fanny Allen Campus in Colchester, which is owned by a Catholic regional health delivery network, Covenant Health, will continue to honor the terms of the lease to Covenant, which states that “consistent with the Ethical and Religious Directives” abortion is “never permitted.” The decision to lift the ban was not intentionally kept quiet, although it might appear so. According to a spokesperson, the hospital does not announce board decisions. Nor does it meddle in medical decision making: “The board does not get involved in decisions about services, but it had to vote to lift the ban,” Stickney explained.

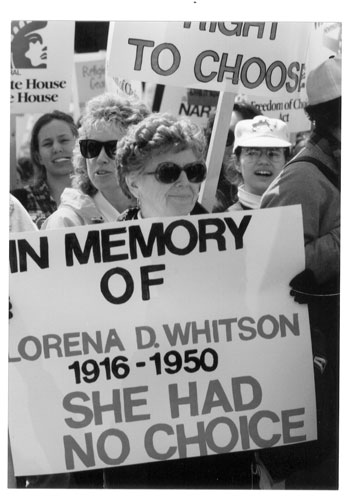

However, the 1972 board did get involved in decisions and banned elective abortion services at the hospital, ostensibly because they were available elsewhere in the community. “The 1972 board was an outlier,” Stickney said. Dr. John Brumsted, president and CEO of UVMMC, reinforced the new attitude.: “Because I also believe that decisions about reproductive health care should be made between patients and their physicians, I support the board’s decision to remove itself from that process by rescinding the 1972 policy,” he stated in an e-mail. How abortion rights were won in Vermont is a story of grassroots organizing, judicial challenges, and pressure from doctors who were close to and understood the need. Dating from 1846, Vermont law stated, in convoluted legislative lingo, “A person who willfully administers, advises or causes to be administered anything to a woman pregnant, or supposed by such person to be pregnant, or employs or causes to be employed any means with intent to procure the miscarriage of such woman, or assists or counsels therein, unless the same is necessary to preserve her life, if the woman dies in consequence thereof, shall be imprisoned in the state prison not more than twenty years nor less than five years. … However, the woman whose miscarriage is caused or attempted shall not be liable to the penalties prescribed by this section.” In other words, it wasn’t a crime to get an abortion, but it was a crime to perform one. One year before the US Supreme Court’s landmark Roe v. Wade decision legalizing abortion nationally, the Vermont Supreme Court tossed out Vermont’s 1846 law. In the precedent-setting “Jacqueline R” case of 1972, a courageous young resident at the Vermont College of Medicine, Jackson Beecham, and a Vermont woman in urgent need of an abortion sued the State in Chittenden County District Court. Defending the law was 22-year-old state’s attorney Patrick Leahy, now Vermont’s senior US senator, and the late senator James Jeffords, then attorney general. In a statement last year, on the January 22 anniversary of Roe, Senator Leahy wrote, “the case, Beecham v. Leahy, quickly made its way to the Vermont Supreme Court. At the time, our state’s high court was comprised entirely of Republicans. Yet the five conservative justices understood what we had been arguing all along—that a statute whose stated purpose was to protect women’s health, and yet denied women access to doctors for their medical care—was sheer…hypocrisy. The court’s opinion rightly questioned: ‘Where is that concern for the health of a pregnant woman when she is denied the advice and assistance of her doctor?’” The court’s 5–2 ruling overturned the law and “was a victory for women’s health in Vermont,” Leahy wrote. The court’s decision left Vermont with no abortion law at all. In less than a year, the picture for women would change dramatically. A core group of organizers quickly mobilized to take advantage of the absence of a law before the legislature could pass a new one—one that would stick. They had to work fast.

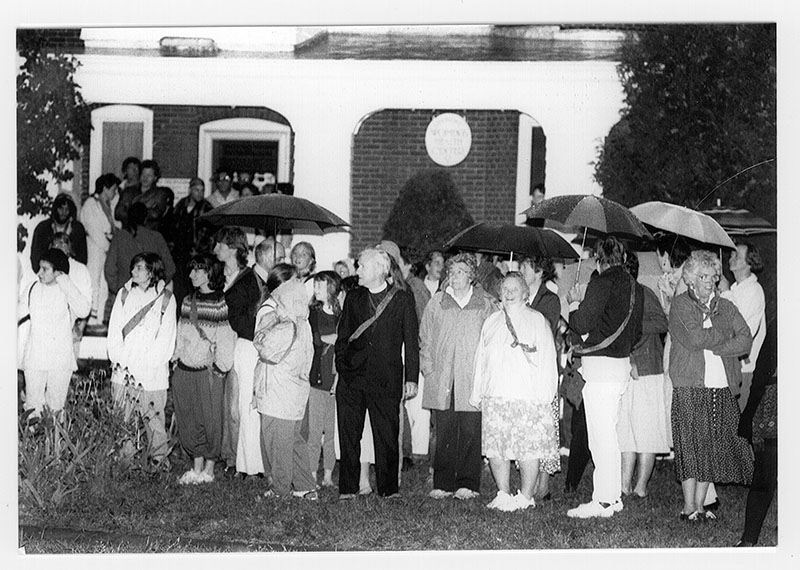

“The impetus came not from the radicals, but from well-connected, upper-middle-class women who took it on themselves to make a change,” said Jennifer Kochman, who served on the first board of directors of the Vermont Women’s Health Center. One of those professional women was business owner Sallie Soule whose role was to rustle up the financing. Soule, now 90 and living in Florida, recalled by e-mail the tense months of organizing a women’s health center from scratch during that narrow window of opportunity. She and her business partner, Priscilla Welsh, who was a founder of Vermont’s Planned Parenthood, hoped Planned Parenthood would open a facility for abortion services, Soule wrote. Welsh talked with her Planned Parenthood colleagues, but they were not ready to take it on at that time. Clearly, neither was then Mary Fletcher Hospital. So the group would have to create a health-care facility on their own. Soule began knocking on bankers’ doors, she said, and eventually secured a $30,000 loan from the community-minded president of the Merchants Bank, Dudley Davis. The Vermont Women’s Health Center would go forward.

That was 46 years ago. Today, the culture surrounding elective abortions has completely changed. UVMMC, which has been through several reorganizations and name changes since that time, now has a board headed by the former CEO of Planned Parenthood, Allie Stickney, who served in that role for many years in several states. Brumsted once practiced obstetrics at the Vermont Women’s Health Center, working with patients who might not have received pre-natal care elsewhere owing to poverty and other risk factors. “My experience there strengthened my belief that all women deserve access to a comprehensive range of family planning services,” he said. And the current medical staff are committed to broadening options for women plus offering a family planning specialization to medical students, as evidenced by the hiring of MacAfee, whose biography on the medical center’s website lists abortion and family planning among her specializations. And although this fact doesn’t directly reflect changing times and attitudes, it completes the picture in a poetic sense: Stickney is now married to the Dr. Beecham of Beecham v. Leahy, who started it all back in 1972. Informed by her international work for Planned Parenthood, Stickney summed up her view about the need for unimpeded access to abortion services for all women: “We forget in this country that abortion is a public health and safety issue. It’s become politicized. Women die every day in other countries where safe abortions are not available. It’s a good change, to join the world where safe abortion is available to all women.” |

|||||

|

Sally Ballin is a writer and educator in Chittenden County.

|

||||