| Artists Hannah Sessions & Bonnie Baird Find Inspiration on the Farm | |||||||||

| by Cynthia Close | |||||||||

|

|||||||||

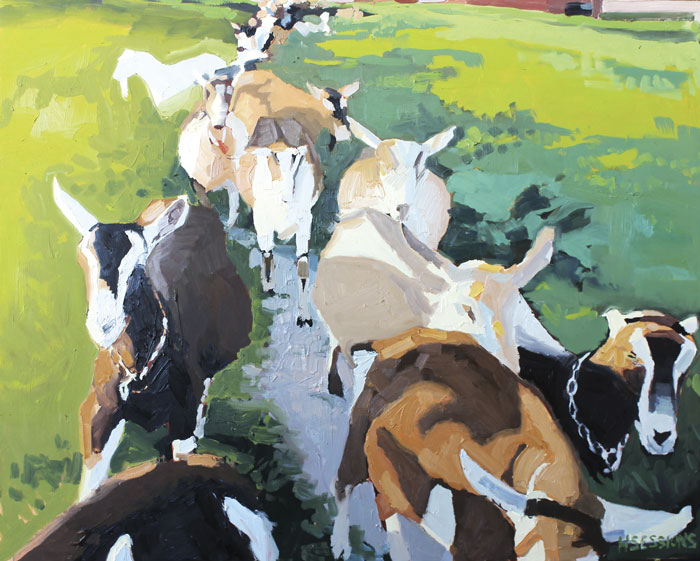

In college, Sessions realized there are a lot of ways to express your power as a woman. Through her research she describes the discovery of a subtle form of feminism, a “domestic feminism” that manifested in women like Susan B. Anthony, the women’s rights activist and suffragette. Sessions informed me that Anthony gave her first speech at a quilting bee. The artistic as well as the political and historical aspect of quilting appeals to Sessions, who notes that “African American women created beautiful quilts out of old grain bags, another example of art, farming and a subversive feminism.” Although her parents were not farmers, they did not attempt to thwart their daughter’s love of animals when, at the tender age of 9, Sessions came home from summer camp with two sheep. She learned to respect the integrity of the animals she raised, and she and her husband have brought that humanistic approach to the goats they manage on Blue Ledge Farm. All the goats have names. They also have the luxury of lounging around the woods and chomping on the grass in the pastures before returning to the barn to get milked, 16 goats at a time, twice a day. In 2016, Blue Ledge was certified as an Animal Welfare Approved Farm. To maintain this certification, the farm must pass an annual inspection, demonstrating that their goats have enough space and time outdoors to maintain their health and happiness.

Respect for the land goes hand-in-hand with caring for healthy contented animals, so it was a logical move when, in 2004, they sold their development rights to the Vermont Land Trust. This decision helped to finance the construction of their cheese room while guaranteeing that their woods, pastures, and wetlands will remain open and undeveloped. Blue Ledge Farm has also partnered on several projects with Efficiency Vermont. This includes variable speed milking machines, efficient cooling compressors, fluorescent lights, and a clean-burning EPA-approved biomass furnace. Their home, cheese house, and barn as well as all of their hot water are fueled by locally produced wood pellets, and in 2015 they covered the south-facing roof of their barn with solar panels, which provides 50 percent of their energy needs in the summer. Interest in artisanal cheese took off right around the time Blue Ledge Farm cheeses started winning awards, making for an ideal confluence of factors. Today, you can find their cheeses at locations throughout Vermont and as far afield as California. You can also order any of the mouthwatering fresh chevres, crotina, camembrie, or the delicately veined Middlebury Blue directly from their attractive and informative website.

|

|||||||||

Artist-Farmer Bonnie Baird |

|||||||||

After Bonnie and Bob Baird bought Baird Farm in North Chittenden in the late 1970s, they spent the next 23 years raising dairy cows while expanding their maple sugaring operation. The cows were eventually sold off, and they went about the business of rebranding the farm. Today, they nurture 11,000 taps producing maple syrup instead of milk.

The Bairds share the same dedication to sustainability and respect for the land that can be found on Blue Ledge Farm. Their Vermont maple syrup is certified organic and must follow a strict set of rules determined by the VOF (Vermont Organic Farmers) and approved by the USDA (United States Department of Agriculture). I, like most people, assumed maple syrup was automatically all natural and organic. But the guidelines for organic demand that maple syrup producers have an approved forest management plan that provides habitats for wildlife, creates biodiversity in the sugarbush, and does not use pesticides. They also must follow the strict VOF tapping guidelines and use an organic defoamer when boiling their sap into syrup. An annual inspection is required to keep their organic certification up to date. With the full support of her family, Bonnie Baird has chosen to focus on her lifelong love affair with art. As a child she had a passion for drawing. Seeing a reproduction of Young Hare, a 1502 masterpiece of realism by German Renaissance artist Albrecht Dürer, made a lasting impression and triggered Baird’s understanding of what art could be. Her teachers, recognizing her precocious ability, encouraged her to go to art school. Being the oldest of six kids, during a time when an art school education was an ill-afforded luxury, made going to a school like Pratt or Rhode Island School of Design out of the question. As a result, Baird has had to cobble together a fragmented series of learning experiences, including a stint with renowned print and book artist Claire Van Vliet and an intensive, relatively recent period of study at the Art Students League in New York City. This farm girl had to overcome city-induced anxiety, but she threw herself into the program, drawing the figure in the morning and painting in the afternoon.

In spite of her ability, Baird “was too scared to be an artist.” Like many other women of her generation, she was working at being a wife and a mother, while juggling the 14- to 16-hour days demanded by the farming life. She tells a story about trying to squeeze some art-making time in the studio when her oldest daughter was 2. She had laid a watercolor on the floor to dry and her daughter walked on it. To salvage the painting, she had to cut off the ruined part and realized that even in its fragmented form she could find an interesting pattern. All the years Bonnie Baird spent immersed in the air, light, rain, wind, heat, cold, mud, and snow on the farm have now coalesced in oil paint on her canvas. Though she rarely paints outdoors, she often takes a notebook and records all she is feeling and seeing, the sounds she hears in the distance or the way shadows fall. These notes sometimes become poems and help her title her paintings, like The Origins of Everything, the 36-by-36-inch piece that opens the lovely but modest catalogue that accompanied her recent exhibition, titled Where to Land, at NODA.

Bonnie Baird has clearly overcome her fear of calling herself an artist. Named “An Artist to Watch” in the most recent Vermont Art Guide is like a coming-out acknowledgment of her talent. The artwork of Bonnie Baird and Hannah Sessions can be seen on their respective websites (www.bonniebairdart.com and hannahsessionsfineart.com) or by request through NODA. |

|||||||||

|

Cynthia Close is a contributing editor for Documentary Magazine, art editor for the literary journal Mud Season Review, and an adviser to the Vermont International Film Festival. She lives in Burlington, Vermont.

|

||||||||