A Cautionary Tale

After women achieved the vote in 1920 with strong leadership from Carrie Catt who helped form the League of Women Voters, she was vilified by the right because she also formed the National Committee on the Cause and Cure of War. In so many words, she was a pacifist, and some conservative women who formed the Woman Patriot newspaper linked Catt and the League to communism and Moscow. The group that lost the battle on the votes for women, the antis, went after the suffrage leaders, and as journalist Elaine Weiss in her new book The Women’s Hour recounts, “they also planted spies in groups they suspected of radical activity, compiled names, created blacklists, made unfounded accusations, and provided unverified information to willing government recipients”—like J. Edgar Hoover. |

photo: courtesy League of Women Voters |

Thus, even with the successful women’s marches in January of 2016 and 2017, and with increased numbers of women running for office in many states, there is again a possibility of splintering into different advocacy groups and facing a backlash from Trump supporters. The history of the success of women’s political participation has not been written.

Women in Power

Vermont and Arizona lead the way with the number of women in state legislatures, with both at 40 percent, and in Vermont, the leadership in both the house and the senate is female. Despite this strong feminine presence, many goals for women and families have not been met in Vermont, among them equal pay for equal work. Maternity and paternity leave is still needed, open flexible workplaces could be arranged, and health care could be implemented for all.

Emerge, a Democratic nationwide organization with local state chapters, prepares and encourages female candidates for office. Ruth Hardy, executive director of the local Vermont chapter of Emerge, based in East Middlebury, is “optimistic” that 2018 will be an “exciting year.” Currently, 19 graduates of Emerge Vermont are vying for office in the November midterms.

Hardy has decided to jump into the race as well: she is running for state senate from Addison County, following the retirement of Claire Ayer. Hardy will be up against another Democrat, Christopher Bray, and a Republican, Peter Briggs: the district has only two seats with three running. She feels that with Senator Bernie Sanders running for re-election, the turnout should be good. Emerge-trained candidates are “strong” ones, she adds.

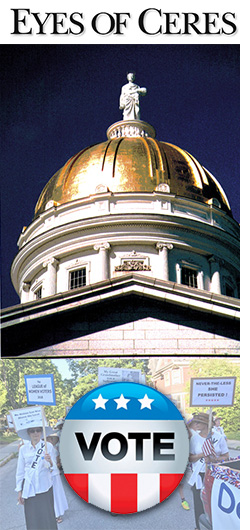

photo: courtesy League of Women Voters

Get Out the Vote

The League of Women Voters (LWV), a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization, began in 1920. It evolved from the National American Woman Suffrage Association, founded in 1890 and dissolved in 1920. The Vermont chapter of the league, with offices in Montpelier, has a little over 50 dues-paying members, including some men. Yes, men are welcome to join the league.

Today’s LWV focuses on voter service and advocacy, according to Catherine Rader, a Vermont member who writes on issues. It works to educates voter and encourages them to attend debates among the candidates and to read their position papers. The league’s website provides a nonpartisan voting guide and other useful information for voters (https://my.lwv.org/vermont), and the league often hosts educational events and forums.

Although the league does not support specific candidates, it does take positions and actions on certain issues. According to their website, “members must study and come to consensus on an issue, in order to form a position.” For example, the LWV is in favor of bicycle paths, walkways, electric-powered vehicles, as well as geographic and intermodal connectivity and renewable energy sources and energy conservation measures. The league supports the establishment of a state bank and favors a Vermont program to provide a basic level of quality health care to residents of Vermont. The complete list of league positions can be found on its website.

In the run-up to the midterms, the Vermont league has tapped into many avenues to get out the vote. In the Northeast Kingdom, league members go to libraries with information, as well as hosting informational tables, such as at the Northern Vermont University’s Student Involvement Fair in Johnson and Danville’s Autumn on the Green festival in October. The league is encouraging voter registration at Phoenix bookstores in Burlington, Essex, Rutland, and Chester.

Many organizations are working to get out the vote for the midterms. Voting for candidates who care about women’s issues is vital. As Gov. Kunin wrote in her 2012 book, The New Feminist Agenda: Defining the Next Revolution for Women, Work and Family: “We have to organize, mobilize, and advocate with a fierce passion at all levels—from the grassroots to the states to Washington, from east to west and north to south, leaving no constituency or person untouched.”

Vermont League of Women voters march in this year’s July 3 parade in Montpelier, dressed as suffragettes.

photo: Jeannette Wulff

|

A Consequential Election

by Kate Mueller

Many consider the midterm general election this year (November 6, 2018) one of the most consequential in decades, given the complete control the Republican Party has of the federal government, headed by a president who many see as, at the least, wrongheaded if not out-and-out reckless and a danger to the republic.

But all the action at the federal level—that could tip Congress toward the Democrats and put the brakes on the Republican agenda—is happening in other states, unlike Vermont where incumbents Rep. Peter Welch (D) and Sen. Bernie Sanders (I) are expected to retain their seats.

At the state level, all the incumbents running for re-election in the executive branch are likely to win: David Zuckerman, lt. governor; Beth Pearce, state treasurer; Jim Condos, secretary of state; Doug Hoffer, auditor; and T.J. Donovan, attorney general. Incumbent governor Phil Scott is favored to win the election over Christine Hallquist, the groundbreaking transgender Democratic candidate for governor.

The big action is happening in the legislature, where all 150 house seats and 30 senate seats are up for election.

Green Candidates

Vermont Woman supports candidates with a strong environmental record. We support Christine Hallquist for governor, with her progressive agenda of following the Solar Pathways Vermont plan for reaching a 90 percent renewable energy supply by 2050 and her goal to oversee the building of a modern state transportation system and encourage more economical and environmentally friendly mass transit options, as well as her support for a universal health-care system in Vermont and paid family and medical leave insurance.

A good source for identifying candidates with a green report card is Vermont Conservation Voters. VCV was pleased to report that all the candidates it endorsed won their races in the August 14 primary. A list of the candidates that VCV endorses for the general election can be found at http://vermontconservationvoters.com/elections/. With climate change becoming an increasingly present threat, it’s more important than ever to put forward-thinking people in state government.

Voting in Vermont

According to a 2016 survey conducted by the Electoral Integrity Project, an academic research project based in Harvard and Sydney Universities, Vermont has the highest electoral integrity of all the states, followed by Idaho, New Hampshire, and Iowa. Vermont is one of the least restrictive states when it comes to voting. In Vermont, you may register to vote up to and including the day of the election, and you do not need an ID to vote, unless you are a first-time voter who registered by mail. If you go to the polls and your name isn’t on the voter checklist, you can still vote: just sign a sworn statement affirming that you are registered. For visually impaired voters, the Vermont secretary of state’s office has a vote-by-phone option. To find out where your nearest polling location is, go to the “My Voter Page” at the Vermont secretary of state’s website: https://mvp.sec.state.vt.us/.

Kate Mueller is the Editor of Vermont Woman

|

|

So Much Change in So Short a Time

by Rickey Gard Diamond

At the end of this month, Sue Racanelli, of the League of Women Voters of Vermont (LWV), is convening the first planning meeting for a centennial celebration in 2020 for women’s suffrage. The Vermont Commission on Women (VCW) is supporting the league in this core effort, says Lilly Talbert, communications and program director at VCW. Vivienne Adair with the American Association of University Women (AAUW) of Vermont is also part of this initial meeting.

Why celebrate? It’s too easy to overlook how recent is women’s organized entry into the public arenas of education, commerce, and politics, once men-only realms. The Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF) was founded in 1915. Vermont’s YWCA is celebrating its centennial in 2019. Vermont LWV and Vermont AAUW were both founded in 1920.

Back in 1776, Abigail Adams admonished her revolutionary husband, John, to “remember the ladies and be more generous and favorable to them than your ancestors. Do not put such unlimited power into the hands of the husbands.” He didn’t, however, heed her advice. While property-owning men have been casting US votes for 229 years, white men sans property for 226 years, and black men for 148 years, women have only had a say in matters for less than half our nation’s history—98 years.

The 19th Amendment to the US Constitution that won women that privilege, though made law in 1920, has a backstory. Vermont women had long been working for suffrage as VESA (Vermont Equal Suffrage Association, previously VWSA) and, as early as 1880, had won the right to vote in state school matters. Later organizers aspired to Vermont being the final state needed to ratify the 19th Amendment, but the governor claimed convening for its vote would cost too much. Tennessee beat us to the honor. When the nation legalized our vote, Vermont’s legislature still had not acted.

Nevertheless, there was joy in the Green Mountains. Vermont women’s self-determination had already run a marathon by then—but more milestones lay ahead. Our more recent successes are best embodied by Gov. Madeleine Kunin, who put so many women in her cabinet and on various boards; there was no turning back to men only. Women are still very much in the running.

I was part of planning the celebration of the 75th anniversary of women’s suffrage, and its culmination was our Montpelier march in the summer of 1995.

It’s astonishing to think about the differences just 23 years have made, since the last suffrage celebration. Our efforts back then focused on adding women’s history to Vermont school curriculums. No, it’s true! March had just been newly named Women’s History Month. Central Vermont AAUW sponsored teacher-project competitions and later cosponsored a teacher’s conference at Vermont College of Norwich University. A community grant from the national AAUW enabled us to bring here Molly Murphy MacGregor, one of the founders of the National Women’s History Project (NWHP).

Based in California, that project had created a brand-new online teacher’s website—websites were novel and exciting in and of themselves back then. The website was, and still is, loaded with books on women’s history and other teaching resources. The goal was to make women newly visible. In those days—not so very long ago at all—history was about kings, generals, and wars. Often, the only women mentioned were Cleopatra and Queen Elizabeth. NWHP surveys found women in only 3 percent of US textbooks at that time.

Although everyone at that Vermont teachers’ conference looked middle class and white, MacGregor emphasized the cultural diversity the attendees represented, which is often part of women’s approach to history. Her multiculturalism was an early version of what is now called intersectionality. These words—diversity and intersectionality—highlight race, religion, and varieties of sexism, class, gender, and culture and show us how biases in the public realm can divide and diminish us all.

Our 75th celebration chose to march down State Street in Montpelier to the Vermont State House because the early suffragettes had marched in city streets to make their ideas known. They often wore grand hats, white dresses, and sashes. While western states were the first to make women’s votes legal, early eastern suffragettes were more often mocked, and sometimes their marches vandalized.

Women stuck it out and answered with sass. One of my favorite retorts to the old notion that women were not fit, or strong-minded enough, to vote is Susan B. Anthony’s: “It was we, the people; not we, the white male citizens; nor yet we, the male citizens; but we, the whole people, who formed the Union.”

US Rep. Jeanette Rankin, the very first woman elected to federal office in 1916, representing Montana, put it more simply: “Men and women are like right and left hands; it doesn’t make sense not to use both.”

Rickey Gard Diamond is senior contributing editor to Vermont Woman and the author of Screwnomics: How Our Economy Works Against Women and Real Ways to Make Lasting Change.

|

|