Middle Eastern Women Artists & the Quest to Build Peace |

||||||

| by Cynthia Close | ||||||

Our Last Supper, Ghada Khunji, photomontage on canvas, 52 x 100 cm.

|

||||||

I AM, at the Cathedral Church of Saint Paul in Burlington, Vermont, is a groundbreaking exhibition of 31 important women artists from 12 Middle Eastern countries. An exhibition of contemporary art by Middle Eastern artists immediately commands our attention, in part because we rarely get to see any contemporary art from this area of the world and rarer still if these works of art are made by women. The 16-month tour of I AM began in May 2017, where it premiered at the National Gallery of Fine Arts, Amman, Jordan, supported by the patronage of Her Majesty Queen Rania Al Abdullah. The exhibit was initiated by Caravan, an international nonprofit arts organization founded by Reverend Paul-Gordon Chandler in Cairo, Egypt. The goal of Caravan is to build understanding and peace among the cultures of the Middle East and the West through visual art. The organization has mounted annual art exhibits since its founding in 2009. I AM: Contemporary Middle Eastern Women Artists and the Quest to Build Peace—the full name of the exhibit—first traveled to London and then toured around the United States, appearing in venues in Washington, DC, Wyoming, Ohio, Washington state, and Tennessee. Burlington is the last stop on its tour. The exhibit will be on display until November 25.

Each artist was invited to create one original two- or three-dimensional piece specifically for this exhibition. Curator Janet Rady, a specialist in contemporary art of the Middle East and director of Janet Rady Fine Art in London, provided artistic guidance to the selected artists. Claire Marie Pearman, Caravan’s director of program development and communications, informed me that the only restriction was that of size. Artwork could not exceed one meter in any direction, in order to limit the expenses of crating and shipping. Surprisingly, the organization did not censor the content of the artists’ work. Although it isn’t possible to get an in-depth view of any artist’s oeuvre from one piece, collectively these talented artists elected to speak with one voice in this show, where the impact of the whole is truly greater than the simple sum of its parts. This is apparent the moment you enter the main cathedral. The Episcopal Church in the United States is one of Caravan’s partners, and Saint Paul’s has been home to Burlington’s Episcopalian community for over 140 years. The original building was destroyed by fire in 1971. The current building, completely redesigned by the local architecture firm Burlington Associates, now TruexCullins, opened in 1973. Built of stressed concrete with warm wood oak and a neutral-toned interior, it was intentionally designed to allow the colorful vestments to stand out, which also makes it a convenient backdrop for exhibiting art. The cathedral has regularly been used as a venue for exhibits, as well as hosting musical performances, because of its superior acoustics. The church staff provided enthusiastic support for this project. The concrete walls had made hanging previous exhibitions problematic. To accommodate these works, most measuring approximately one meter by one meter, a substantial, attractive wooden edging was permanently installed along the walls of the entire interior space, allowing for a much easier installation process for this show and all future art exhibitions that the church may choose to host.

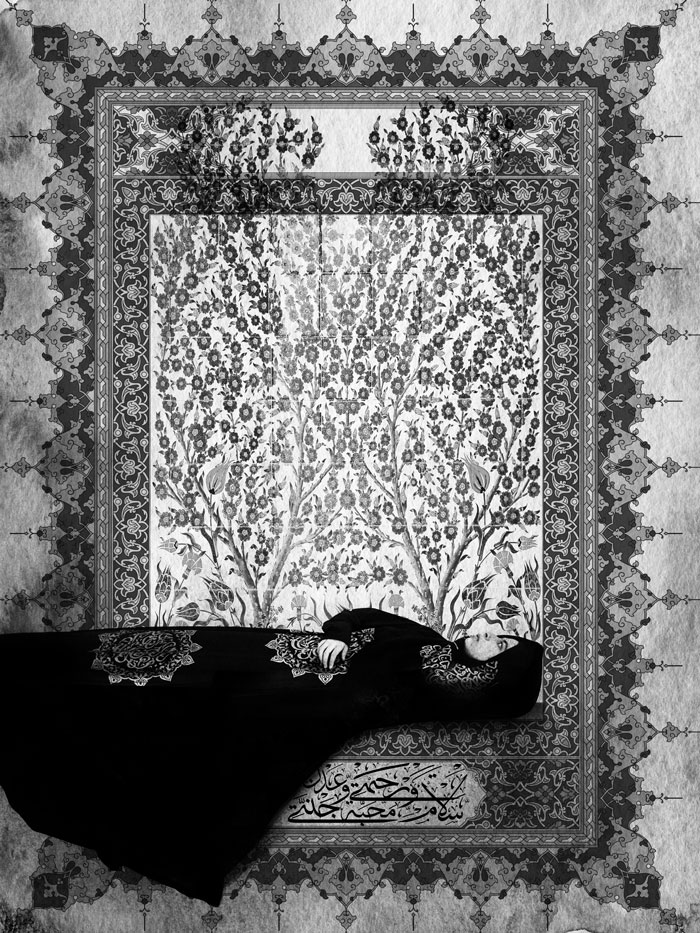

In addition to its message of peace, this exhibit seeks to dispel stereotypes about Middle Eastern women—that they are all oppressed, have fewer rights, and are not in positions of leadership. Rather than focus on inequality, this exhibit highlights the strength and creativity of these women and the contributions Middle Eastern women artists are making to the global culture. The artists’ use of digital media, their sophisticated imagery, and their educational backgrounds challenge the stereotypes. Some, like the Iraqi artist Hanaa Malallah, have PhDs in philosophy and art and have earned an international following. Eden, a large, black-and-white digital photomontage by the young Egyptian artist Marwa Adel, was my personal favorite in the exhibition. A single, horizontal, enigmatic female figure, robed in black, reclines near the bottom edge of an intricately patterned frame, suggesting a fairy-tale-like “Sleeping Beauty” character, or perhaps Hamlet’s Ophelia in death. In 2012, Adel was the recipient of both the Golden Prize at the ninth European-Arab Festival of Photography in Germany and the best Arab Photographer Award at the Emirates Photography Competition in Abu Dhabi. Her work would be a standout in any American art gallery.

The Secrets They Carry, another powerful work in black and white gouache and ink on board by Arab-American artist Helen Zughaib, communicates its message literally and symbolically. Born in Beirut, of a Lebanese father and an American mother, Zughaib was forced to leave Lebanon with her family in 1975, at age 16. She attended high school in Paris and later Syracuse University, New York, where she earned a BFA. She currently lives in Washington, DC. In her piece, a simple white shape suggesting a figure wearing the abaya, the black robe some women in the Arab world wear, held the central space in a field of black, suggesting a ghost-like apparition. Laid over the image is a handwritten Arabic proverb, loosely translated to mean, “There are many secrets hidden under the abaya.” The saying, written over and over in tiny Arabic letters, creates the effect of a lacy veil draped over the figure. The artist in her statement says that she thought, as she repeatedly wrote the Arabic proverb, “about the many secrets and stories hidden beneath her abaya. What has she seen, what has she heard? I thought about her strength as a woman, her beauty, her power, especially in the face of adversity, war and displacement. I thought about her protecting her children, wanting only peace and prosperity for them. I thought about her ability to persevere in any circumstance she faces.” Zughaib’s work has been exhibited worldwide. She believes the arts are an important way to shape and foster dialogue between the West and the Middle East, especially since 9/11 and the resulting crisis across the Arab world.

Ghada Khunji was born in Bahrain in 1967. She lost her father at a very young age, an event that had a powerful influence on her perception of the world. Early religious training was also pivotal, and Khunji elected to reinterpret Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper as a photomontage on canvas for this exhibition. In her version, a female figure, perhaps Mary from Magdala or Jesus’s mother Mary, occupies the center of the composition. This reimagining of an iconic image accepted as gospel in many religions might have been considered blasphemous in another context. The fact that it hung, in this church, right up front next to the altar speaks to the freedom extended to all the artists, without censorship, which is pretty amazing when we look at some of the efforts of right-wing political and religious figures in this country today, who attempt to censor and subvert all who disagree with their worldview. A piece called Keys is a striking photograph of an attractive black-haired woman, with long woven lashes entangled with tiny keys dripping from her tightly closed eyes. The photographic work, which also graces the poster advertising the exhibition, is by Palestinian artist Raeda Saadeh. Born in 1977 in Umm al-Fahm, Israel, the artist now lives and works in Jerusalem. In her statement, Saadeh says, “The woman as an occurring subject in my installations or performance work is represented as living in a state of occupation … the woman I represent lives in a world that attacks her values, her love, her spirit on a daily basis, and for this reason, she is in a state of occupation.”

Rania Matar was born and raised in Lebanon but moved to the United States in 1984. Trained as an architect at Cornell University, her current focus is photography, a subject she teaches at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design. Her two photos, Jaqueline & Juliette, Beirut, Lebanon and Wafa’a and Samira, Bourj El Barajneh Palestinian Refuge Camp, Beirut, Lebanon, are part of a series titled Unspoken Conversations, exploring womanhood at two important stages of life, adolescence and middle age. In these pieces, she has included both a mother and daughter in the same frame. Of all the artists, Matar seems to straddle her identity as a Lebanese-American, giving equal weight to both US and Middle Eastern influences. This tension was evident in her work. In the catalogue introduction, the reverend Chandler tells us, “This I Am exhibition originated from a desire to creatively and positively build on the message of the highly-acclaimed book written by former US President Jimmy Carter, who is much loved and respected in the Middle East, titled A Call to Action: Women, Religion, Violence, and Power.” In closing, Chandler quotes Elif Shafak, the award-winning novelist and most widely read woman author in Turkey: “In art, there is no them. The other is me.” This exhibition has succeeded in helping me to see the art of Middle Eastern women with fresh eyes. I have no doubt many people who have viewed I AM as it migrated on tour from venue to venue have left the exhibition with a new recognition of the powerful role women artists play in furthering a more accepting and harmonious world.

|

||||||

|

Cynthia Close is a contributing editor for Documentary Magazine and an adviser to the Vermont International Film Festival. She lives in Burlington, Vermont.

|

|||||