| A Short History of the Lesbian Feminist Origins of Gay Liberation in Vermont | |||

| by Peggy Luhrs | |||

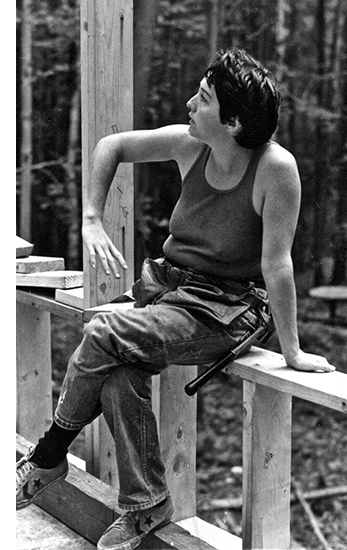

Before this, I had been in a consciousness-raising (CR) group for several years. CR groups were the building blocks of the women’s liberation movement (WLM). In this day of sharing all on social media, it is hard to remember, or imagine if you are young, that there was a time when women barely talked about their sex lives, when every woman thought her problems were strictly personal. That group was invaluable to my development as a feminist. During meetings, we could work out problematic relationships with parents and partners, finding commonality and realizing our struggles were not ours alone. Around this time I read The Woman Identified Woman and was instantly engaged. A 10-paragraph manifesto published in 1970, it was first distributed during the Lavender Menace protest at the Second Congress to Unite Women in New York City, on May 1, 1970. This informal group of radical lesbian feminists had formed to protest the exclusion of lesbians and lesbian issues from the feminist movement at the congress. Their name was an ironic commentary on Betty Friedan, who had argued, during a 1969 NOW meeting, that outspoken lesbians were a threat to feminism and had referred to them as the “lavender menace.” One of the founding documents of lesbian feminism, this manifesto is considered a turning point in the history of radical feminism and was written by six women, among them Rita Mae Brown and Artemis March, who called themselves the Radicalesbians. Some of the writers were members of a communal lesbian group in Washington, DC, called the Furies Collective. The manifesto’s opening sentences were: “What is a lesbian? A lesbian is the rage of all women condensed to the point of explosion.” It well expressed, I thought, the fury we women feel in recognizing how we had been stifled, how we had been kept from knowing ourselves as lesbian, how our talents had been minimized or ignored. It followed the WLM’s understanding of male identification as one of the ways women internalized sexism. Being woman identified meant being a woman whose primary working relationships are with and for women. I brought the manifesto to the CR group, but the others did not share my enthusiasm. I came out to the group as a lesbian—the only one to do so. The other women responded with, in the hippie parlance of the day, “that’s heavy.” I began to seek the company of lesbians. When I told Pam, a lesbian I met through George, that I was a lesbian, she hugged me and said, “Great.” I was healthy enough to know that was a better response than the distant one I had gotten from my CR group, so I left the CR world and entered the well of lesbianism. And I flew out. In a dream I had at the time I rode a motorcycle and then jumped over a fence and ran through an open field. I understood so much of my past angst, and I was happier than I could remember. No, it wasn’t that easy. I lost an apartment due to the landlord’s homophobia. Much of the women’s liberation movement I worked so hard for was worried about the “lavender menace,” as Friedan had named it. I was pilloried by my ex-husband’s second wife who was convinced I wanted to make my son gay. I didn’t. Why would I, so aware of the damage done by having my sexuality repressed, want anything else for my child but the freedom to be who he was? I later lost a job for having a Take Vermont Forward bumper sticker. I had to find a way to make a living. Faye left her nursing job and soon after we started Coven Carpentry, the first all-women construction company. It was tough as each job required its own consciouness raising, but we kept getting work—though too often all the small jobs the men didn’t want. During our time together, Fay and I focused on each other and on building a lesbian community. We initially organized women-only dances then homosexual dances that included gay men. These were held in a space on a second floor of a building on the northwest corner of Church and Bank Streets in Burlington. A women’s center on North Winooski had closed, and we opened the Women’s Switchboard, supported by monthly community donations. Switchboard took calls, connected women, and advocated for them. An early victory was helping a woman keep her child, who she was in danger of losing to social services after she kited a check. In the same building was the Unity Players, a group of women thespians who rehearsed in the next room and performed Edward the Dyke, based on the title poem of poet Judy Grahn’s book Edward the Dyke and Other Poems, in Battery Park with Roz Payne playing Edward’s therapist/interrogator. (Payne, a film maker, journalist, Black Panther historian, and communard, died this past May, 2019.) |

|||

|

|||

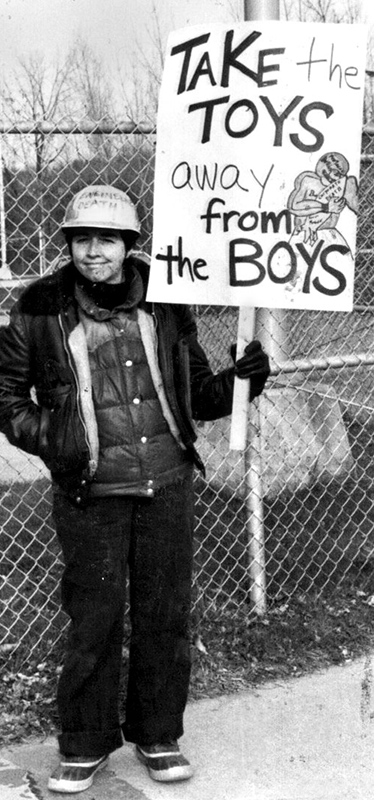

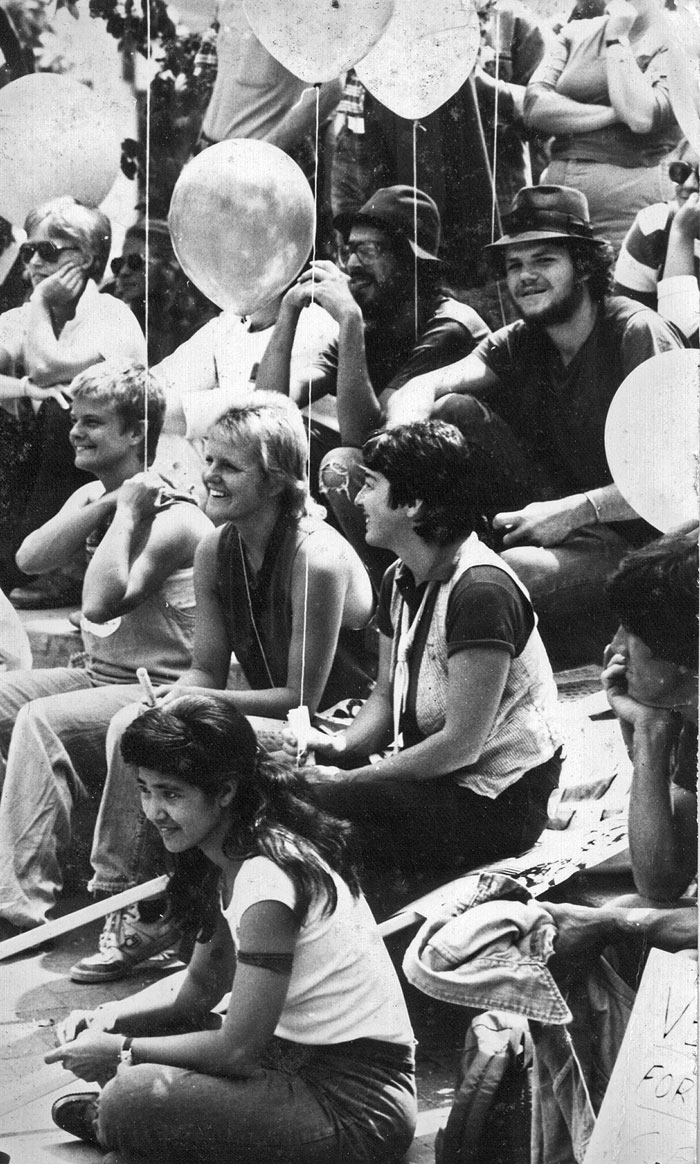

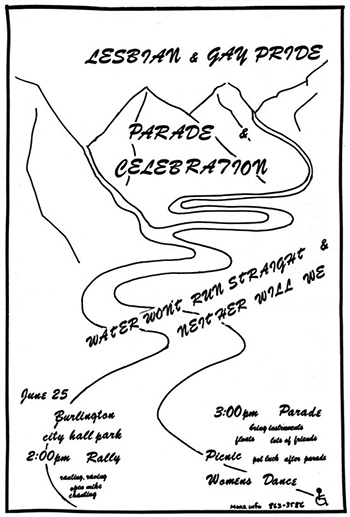

The high school kids were open and honest and just curious. The med and psych majors always wanted to focus on the supposed pathology of homosexuality. I remember doing quite a few of these presentations with Bill. One memorable day when Bill couldn’t make it to Burlington High, another guy, Donald, showed up to be my co-presenter. Donald decided he wanted to talk about S&M to this class. I certainly did not. This was the one and only time I worked with Donald, and my experience was an early indicator of the rifts that would later form in the early LGB community around lesbian feminism and the gay male commitment to a masculinized sexuality. In 1978 a group of us who had worked together on many issues created Vermont’s first women’s newspaper CommonWomon. Euan Bear, Laurie Larsen, Diane Kendrick Mueller, and myself made up the editorial collective, and Lynn Vera, Linda Wittenberg, Robin Mide, and Glo Daly were in the layout group. We named the paper, an irregular periodical, after a collection of poems of the same name by Grahn. Most of the volunteer staff were lesbians, but most articles were about women’s issues in general. In one issue we featured photos of up to 50 lesbians from Burlington who attended, in 1977, the 2nd Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival, staffed and run exclusively by women. The 1970s were a time when many young people were exploring alternative lifestyles and forming communes, and a couple of lesbian communities sprang up. Joyce Cheney was one of the founding members of the Redbird Collective, which started as a group of people living in a household in the Old North End in Burlington (she writes about her experiences in her book Lesbian Land). Eventually eight women with three children bought land in Hinesburg and built a house. The collective dissolved in 1979. The collective that I was involved with was HOWL, Huntington Open Women’s Land (or, as a local man named it, Huntington’s Own Wild Lesbians), which formed in the mid-1980s. The CommonWomon collective began to look for land that would be open women’s land. The pitfalls of that strategy could fill a book. We found a hundred acres in Huntington at the end of a town road with a funky but serviceable house. With a lot of fundraising and great assistance from Janet Hicks, we ultimately secured 50 acres near the Camel’s Hump trail. Many wonderful conferences, singalongs, and various workshops were held there, and a variety of women made it their home. HOWL continues to this day as a nonprofit organization with currently five members in the collective, Glo Daley (one of the original members), Stephie Smith, Cynthia Feltch, Michele Grimm, and Lani Ravin. I remember thinking in 1983 that I’d been out for 10 years and it was time for a lesbian and gay pride celebration in Burlington. I brought this idea to CommonWomon, and Linda Wittenberg was thinking along the same lines. The whole collective was excited to do this. We secured a small grant from the Haymarket People’s Fund, in Boston, which gives money to grassroots groups committed to change, and launched the Vermont Lesbian and Gay Pride. A gay men’s discussion group joined us to organize the day. Three hundred people marched in that first Vermont outing. I recognized many on the sidelines as well. We rallied in City Hall Park, and Michiyo Fukaya, feminist poet and activist, was a main speaker. The press was there to document this first-time event. Sometime later, the participants gathered together for quiche baked by the men and deli food brought by the dykes to celebrate and evaluate. One guy, an IBM worker, told his story of arriving at work to find his colleagues had spread out copies of the Free Press where he was clearly identifiable in the front of the parade. It took courage to march in Burlington, Vermont, a small enough place to be recognized and possibly penalized for it. These were the days when UVM ran a gay conversion program and there were no nondiscrimination ordinances. In its heyday, during the civil union struggle, from about 1998 to 2002, the LGB Pride sometimes had as many as 2,000 marchers. For many years the pride parade was preceded by speeches and music and had a political content. I gave quite a few of those well-received speeches. The politics were taken out by subsequent pride organizers who preferred to focus on drag shows. The desire to be acceptable and assimilate was winning the day, with the pros and cons of that approach. Churches, late to the party, were nonetheless given a prominent position in the parade to showcase the parade’s growing respectability. In 1985 I became the director of the Burlington Women’s Council, which had member representatives from women’s groups in Burlington, ranging from the Women’s Rape Crisis Center to the American Association of University Women and at-large members as well. Bernie Sanders was mayor the first year I was there, and he supported our work with women in the trades and gave us city money to run a self-defense program for women and girls. We did a yearly series of community forums. One was on homophobia, but we then started calling the forums Positively Lesbian to accentuate the positive. Christine Burton, the founder of Golden Threads, a meet-up for older lesbians, was a memorable speaker, as was Dolly Fleming, who had always insisted on nondiscrimination policies in organizations she worked for, which ranged from Community Action to the United Way. In 1992 I testified on behalf of the nondiscrimination act for lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals. During the hearing, we heard varied versions of homophobic hate from the right wing. It was the viciousness of the right and their attacks on legislators that turned the tide. Legislators had not believed our stories of discrimination and hate crimes. When they were exposed to it personally, they realized it was true, and this turned some Republicans, previously opposed, in our favor. Vermont would go on, with the brilliant leadership of Beth Robinson and Susan Murray, to pass civil unions in 2000 and later same sex marriage in 2009, making history not only in Vermont but the nation for being the first state to pass same-sex marriage through the legislature and not the courts. For me it was always about lesbian feminism. At the same time, I believed in a big tent and in welcoming all kinds of lesbians and gays and bisexuals to pride. One year after a speech referring to lesbians and gay men, my good friend Martha said, “Why do you leave out the bisexuals like myself who show up every year to support?” I was both moved and chastened and never left out the bisexual supporters again. I was one of the first liaisons from the gay community to the governor along with Keith Goslant representing the men. Madeleine Kunin was governor and friendly to the cause. Sadly, my memory of that meeting is her imposing presence in large shoulder pads, so different from the woman I had met years back, at the Vermont Women’s Health Center, seeking support for her first campaign for the legislature.

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

There is a movement worldwide, which hasn’t hit Vermont yet, to “Get the L Out”—that is, get the L (lesbian) out of LGBTQIA. This movement disrespects and attempts to erase lesbians. The new category is queer, a word I once embraced and now feel has stretched to include so many factions that it is meaningless. Lesbian feminism is about equality, not just under the law but within relationships and groups. It challenges the hierarchy that male dominance depends on and challenges men’s rights of ownership of women. It stresses the need for women to organize with women as a whole. Women are not oppressed for their gender identity but for their sex. Abortion laws, lower pay, rape culture, vile quasi-religious practices like genital mutilation are all about our sex, not our identities. These days my lesbian activism is online and on YouTube and a monthly show on CCTV called the Feminist Media Review. The YouTube presence, which I hope to increase, has been very gratifying. There are young lesbians out there eager to hear about lesbian liberation, and their feedback has encouraged me to work on a subject I personally know from the inside out and from the myriad books I have on feminism and lesbians. Loving women is not an easy practice to follow and being a lesbian feminist has had costs economically and socially, but oh the company and the music and the visions Wouldn’t have missed it for the world.

|

|||

|

Peggy Luhrs headed the Burlington Women’s Council from 1985 to 1995 and taught ecology and feminism at the Institute for Social Ecology at Goddard College, Plainfield. She continues to educate and organize, online and locally.

|

||