| We Won't Go Back: Vermont's History to Legalize Abortion 1972 | |||

by Cyndy Bittinger

|

|||

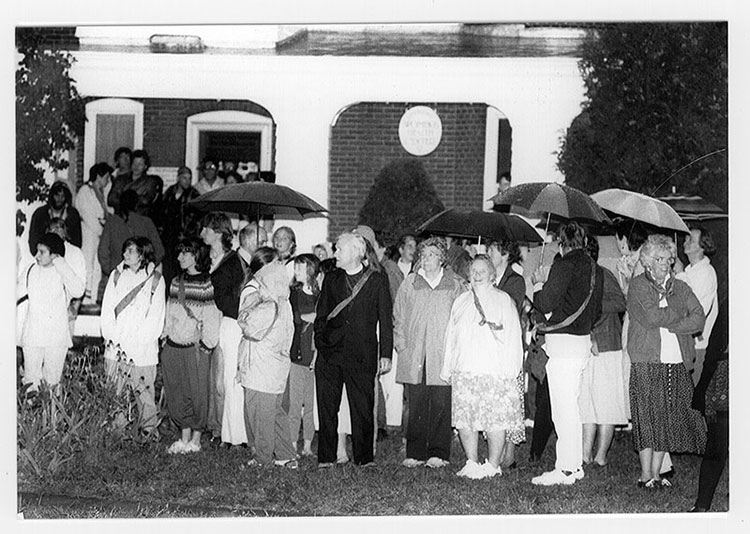

Operation RescueattacksVermontWomen’sHealthCenter,Burlington inthemid1980’sTheyattemptedtooccupythecenterandprevent

|

|||

Vermont was the second state to decriminalize abortion in 1972 --a year before Roe v. Wade made it legal nationwide. Home-Grown History

At the time, 1972, a legal abortion could only be attained in New York, which two years earlier had become the first state to legalize the procedure. A New York Times headline said the state law “stunned” the nation. Gov. Nelson A. Rockefeller had signed the bill, passed by both houses of a legislature controlled by his fellow Republicans. Only four of 207 legislators were women. But Vermont women who could not afford bus fare to New York and medical costs often turned to self-abortion. In those days, hospitals in Vermont and every large city around the country had a septic ward for desperate women who had attempted to abort on their own.

The Back Story The danger of infection, sterility, and death from botched abortions motivated Beecham and other medical professionals in Vermont and around the country to work to overturn abortion bans. Among doctors, decriminalizing abortion was not a new idea. In 1933, Dr. William J. Robinson wrote a book The Law Against Abortion: Its Perniciousness Demonstrated and Its Repeal Demanded. Dr. A.J. Rongy also advocated an expansion of therapeutic abortions in his book, Abortion: Legal or Illegal? Neither books were widely read; media avoided the topic. Historian Leslie J. Reagan traces this era in her book, When Abortion was a Crime: Women, Medicine, and the Law in the United States, 1867-1973. European movements had long demanded legal abortion as a right and method of birth control, especially for working class women. Abortion was legal in England by 1967. In contrast, the U.S. birth control movement led by Margaret Sanger did not want contraception equated with abortion. It withdrew from the political left to link with middle class professionals. Effective birth control, they argued, could even eliminate the need for illegal abortion. In 1936, another American doctor, Frederick J. Taussig, suggested a middle path: Let physicians give abortions in hospitals after consultations with fellow doctors to monitor the ethics of the decisions. Then, abortions could be arranged for rape victims, the retarded, and those under 16 or too poor to feed another mouth. In the 1930s, many hospitals accepted these recommendations. But a cultural backlash in the 1940s encouraged women to go back to traditional roles and bear more children. Meanwhile abortion had become safer, with the availability of blood transfusions, sulfa drugs and penicillin. Even so, the political and legal climate curbed abortions during the 1940s and 1950s. Sex and Dying “The near impossibility of obtaining birth control in the 50s and 60s,” writes Reagan in When Abortion Was a Crime, “raised the danger of intercourse and the fears felt by single women.” This frustration finally culminated in a movement of women, doctors, and lawyers to loosen the tightening knot around women’s choices. Feminists declared lack of access to safe, legal abortions a collective problem for all women. A frequent method for an illegal abortion was using potassium permanganate or another irritant to force uterine contractions. Complications included severe pelvic inflammation and infection with pelvic abscesses, which had to be drained. And death. Historian Reagan documents many fatal complications from various methods of illegal abortions: Uremia causing severe infection leading to septic shock and kidney shutdown, gangrene or tetanus; and hemorrhage from perforations. Septicemia or peritonitis ended the lives of 60-70 percent of women in septic wards in the 1930s. Even in the 1950s, septic abortion wards in cities usually had 15 or more extremely ill women suffering in their beds. The number of deaths from botched abortions increased in the 1950s. Women of color or in poverty had a much higher incidence of death. Confirming Reagan’s research, Dr. Judy Tyson, who was formerly with Vermont Planned Parenthood and the Vermont Woman’s Health Center, told Vermont Woman that she witnessed the heart wrenching suffering of 25 to 30 women in the septic wards when she was an intern with a New York City hospital. “Jacqueline R” and Dr. Beecham In January of 1972, “Jacqueline R.” and Jackson B. Beecham, M.D. filed a case against state’s attorney for Chittenden County, Patrick J. Leahy and Vermont’s Attorney General James M. Jeffords, asking for a declaratory judgment on the validity of the abortion statue in front of the Supreme Court of Vermont. “A medically induced and supervised abortion is medically indicated in order to secure and preserve the plaintiff’s physical and mental health,” Beecham argued. Actually, it was not a crime for a woman to have an abortion, but a doctor who performed one faced three to 10 years imprisonment, raised to five to 20 years if the patient died. “Tragically,” the plaintiffs argued, “unless her life itself is at stake, the law leaves her only to the recourse of attempts at self-induced abortion, uncounseled and unassisted by a doctor, in a situation where medical attention is imperative.” Finally, they argued that because the legislature had affirmed the right of a woman to abort, it “cannot simultaneously, by denying medical aid in all cases where it is necessary to preserve her life, prohibit its safe exercise.” The Vermont Supreme Court sided with Beecham and “Jacqueline R.” However, although unenforceable, the statute is still on the books. There is currently a legislative effort to remove it, bill S.315. But it took a nun to make abortions accessible. The late Sister Elizabeth Candon, then president of Burlington’s Trinity College (since closed), helped to organize the first clinic, according to Tyson. Candon was part of an almost 100-member clergy group that grappled with contraception and abortion in relation to women, health, family and poverty. Sister Candon later served on local, state, and national committees that helped institute policies that empower women in their decisions for birth control and family planning. In 1976, Gov. Richard Snelling appointed her secretary of the Agency of Human Services, where she made Medicaid funds available for abortions.

The group formed committees, according to Tyson, to find a site, doctors, and funding. Some “bankers, lawyers, nurses, and doctors” met in a basement on Church Street to set up the Vermont Women’s Health Center in Colchester, which then was moved to Bank Street, then to North Avenue in Burlington, said Tyson. This was the first “women-controlled” U.S. health center to offer abortions, according to health provider, Sue Burton of Burlington, in her 1987 oral history project account. A bank did help with funding, said Twitchell, but added that the older women in the group, an unspecified number, had each signed a note for $5,000 in support of the clinic. Drs. Judith Tyson and Emma Wennberg (now Ottolenghi) were hired as regular clinic physicians. Both physicians–along with about ten other women of different professions, backgrounds and ages–staffed the clinic, which offered a wide range of services including counseling. Ottolenghi supported the cooperative operation because of her strong pro-choice beliefs, she explained to Vermont Woman earlier this year. She had served as a clinician with Tyson in the “Under 21” Planned Parenthood clinic, which provided services and contraceptives to under-age females without requiring parental consent. Ottolenghi also worked at the UVM Student Health Center, where she provided contraception to students, reinforcing her awareness of unmet needs. Tyson, who volunteered at Planned Parenthood, also gave pre-natal care at the Lund Home for Unwed Women, where pregnant teens had limited options: keep the baby, or give it up for adoption. Once abortion became legal, a third option was available. And for some this was “like night turned into day,” said Tyson.

Backlash Reaches Us Politically, not all was smooth sailing in Vermont. In 1979, Sen. Melvin Mandigo of Bethel proposed denying federal funding to Planned Parenthood. Sen. Chester Scott of Windsor County added that Planned Parenthood “should disassociate itself from any abortion activities or forfeit all federal funding.” The Senate vote was 15 to 15, when Lt. Gov. Madeleine Kunin broke the tie. The new law made Vermont a target for national anti-abortion forces including Operation Rescue who through the 80’s and 90’s staged ugly, dangerous large-scale protests, blocking women from entering the clinic. The mostly out-of-state protestors were willing to be jailed for civil disobedience. A Molotov cocktail was placed near a St. Albans Planned Parenthood facility. Tyson recalled that some at Burlington’s center wore bullet-proof vests, and many faced harassment and threatening phone calls. She also remembers walking through the picket lines, but characterized them as noisy, not dangerous. Rachel Atkins, the long-time executive director of the Vermont Women’s Health Center, expressed her concern in 1998 to reporter Terry Allen of The Vermont Times, “We have gone from a period when abortion was illegal AND women were dying, to one in which providers are dying.” Allen’s article ended by concluding that “The increase in violence has coincided with a decrease in open, grassroots activism.”

|

|||

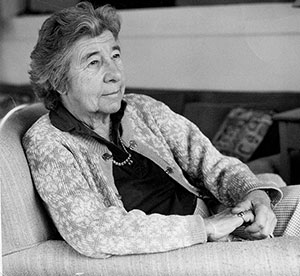

| Writer and historian Cyndy Bittinger teaches at Community College of Vermont, and regularly presents women’s history on Vermont Public Radio, most recently on Grace Coolidge. Her latest book is Vermont Women, Native Americans and African Americans: Out of the Shadows of History.

|

|||