| Madam President: The Struggle to Break the Last Glass Ceiling |

|||||

|

|

||||

Victoria Claflin Woodhull |

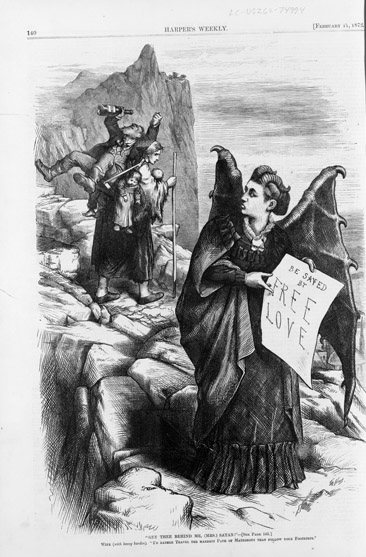

Victoria Woodhull The first woman to try to run for the presidency really did it as a lark in 1872. She was young, only 34, and not really qualified for office. She could not even vote, but that is why she tried for it—to focus attention on the fact that women did not have this basic right, the right to vote. When the famous suffragist Susan B. Anthony stated in 1860 that “cautious, careful people always casting about to preserve their reputation and social standing, never can bring about a reform” she might have had Victoria Woodhull in mind—a bold figure who threw caution to the wind. Her life story is remarkable—a poor child who eventually rose to the highest ranks of New York society. Woodhull had a Wall Street brokerage firm and a weekly newspaper with articles urging reform—both firsts for women. She was a famous spiritualist speaker and once argued before the Judiciary Committee of the House that the 14th and 15th amendments to the Constitution actually did give women the vote. |

||||

| But Congress did not agree, and so she suggested that women hold a constitutional convention and elect a new government. She urged women to revolt: “We are plotting Revolution!” In 1875, the Supreme Court ruled that voting was a privilege, not a right of a citizen. Women remained disenfranchised.

Since the mainstream political parties would not let women join or vote, Woodhull launched her own party, the Equal Rights Party, in 1872, with the goal of running national candidates. At a party meeting, she stated that “a revolution shall sweep over the whole country, to purge it of political trickery, despotic assumption, and all industrial injustice.” She was nominated as the presidential candidate by acclamation of all at Apollo Hall in New York City. But Harriet Beecher Stowe, famous author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin and advocate of married women’s rights, warned that any presidential candidate must expect to “have his character torn off from his back in shreds and to be mauled, pummeled, and covered with dirt by every filthy paper all over the country. And no woman that was not willing to be dragged through every kennel, slopped into every dirty pail of water like an old mop, would ever consent to run as a candidate.”

|

|||||

Lawyer Belva Lockwood |

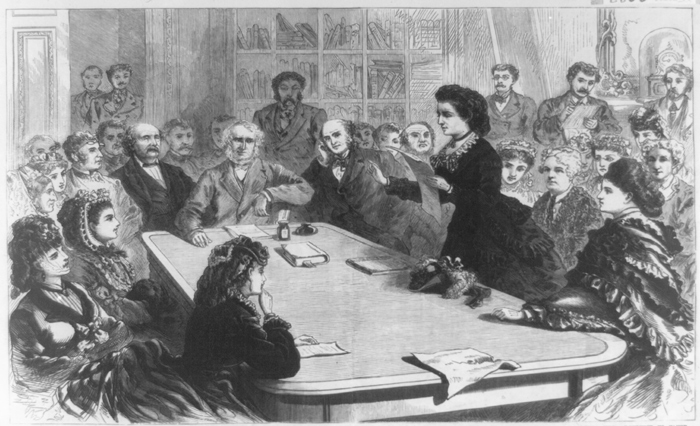

Belva Lockwood Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg wrote in the introduction to a recent book that she admired a female presidential candidate from the 1880s for her persistence and determination. And no wonder. Belva Lockwood was born in Royalton, New York, in 1830. By age 14, she was teaching school. She married and had a child, but her husband died and left her with no money. She earned a college degree and began a teaching and administrative job at a high school, but noticed her pay was half of what the male teachers received. Still striving for a better salary, she moved to Washington, DC, where she applied to law school—but was turned down because she was a woman. When she eventually did attend a newly formed law school, she was denied a diploma even though she passed all her courses. Only her appeal to a school trustee finally produced the sought-after certificate. |

||||

In 1880, Lockwood became the first woman to practice before the US Supreme Court—after convincing Congress to pass an act to allow her to do so. Among other cases, she won a multimillion-dollar award for Cherokee Native Americans—at age 75. But as she campaigned by rail from Louisville, Kentucky, to New York, she was harassed by men dressed in comical Mother Hubbard dresses with bonnets and aprons. Lockwood herself saw her candidacy as “the entering wedge, the first practical movement in the history of woman suffrage.” Unfortunately, Susan B. Anthony, the most visible advocate for suffrage, had no use for minor parties and did not lend her support. Lockwood had to petition Congress to have her votes counted. Her supporters had seen their ballots ripped up or dumped into wastebaskets as false votes. Only 4,100 were counted. But given that women couldn’t vote, along with a lack of support from the press, it’s remarkable she received any votes at all. Belva Lockwood ran for president twice, in 1884 and 1888, and was the second woman to run for the presidency after Victoria Woodhull’s attempt in 1872. She’s famously quoted as saying, “I cannot vote, but I can be voted for.” |

|||||

|

|||||

But Governor Percival Clement did not support suffrage for women. He was for local option on prohibition, which would allow each municipality to decide whether to be wet or dry, and was angry at women in the temperance movement. He refused to call for a special session in 1920 to consider suffrage. That honor went to Tennessee—much to the consternation of Parmelee and her sister suffragettes. |

|||||

Eighty-Year Gap Eighty years would pass before another woman dared to run for president in 1964. Why so long? Summing up the many years of women’s history in a few sentences is quite a task, but to quote Carol Hymowitz and Michaele Weissman from their book A History of Women in America, “The 19th century pattern of discrimination against working women continued into the 20th century. Women were poorly paid, segregated in ‘female’ jobs and treated as temporary workers by employers, unions, and the public.” The white-collar workforce expanded; from 1920 to 1940, 25 percent of this workforce consisted of women. With the New Deal in the 1930s, women flocked to Washington, DC, to work as reformers. Yet childcare was lacking; the federal government provided some in 1944, but only 10 percent of the children were covered. As Hymowitz and Weissman report: “In the 1950s the propaganda against career women took a particularly scurrilous tone.” Female ambition was characterized as “a form of mental illness” with repercussions on husbands and children. It’s not surprising, then, that decades would go by before another woman, once again, attempted to scale the presidential peak. |

|||||

Margaret Chase Smith It was at the Republican Convention of 1964 that a major political party for the first time nominated a woman, Margaret Chase Smith—only to be defeated later by Senator Barry Goldwater from Arizona. “Barry stews, Rocky pursues, Dicky brews, but Margaret Chase Smith wows and woos with blueberry muffins” was the slogan written on one of her campaign posters. Not really a great start for a candidate, but Smith had conflicted views about running as a woman in 1964. She was born in Skowhegan, Maine, to hardworking parents, and she had jobs starting at the age of 12. When she married Clyde Smith, she became his assistant in his congressional office in 1936. When he died in 1940, she ran and won a special election, making her the first woman elected to Congress from Maine. One of her legislative accomplishments was to integrate women into the armed forces. Winning a Senate race in 1948, she became the first woman to serve in both the House and Senate. To this day, Smith remains the longest-serving Republican woman in the Senate. When Joseph McCarthy began a hunt to root out Communists in the government, in 1950, she denounced his policies by declaring, “I don’t want to see the Republican Party ride to political victory on the four horsemen of calumny—fear, ignorance, bigotry, and smear.” |

|

||||

George Aiken of Vermont signed her Declaration of Conscience along with five other senators, and he encouraged her presidential campaign. She entered state primaries but could not campaign very much since she had to serve in the Senate. She turned down funds and refused to buy television time. Her campaign was independent and inconsistent. She tried to be feminine, giving out recipes and muffins, but she also wanted to appear presidential. An editorial in Time magazine termed her run “frivolously feminine.” Aiken praised her saying, “If she were a man with her ability she’d get the nomination on the first ballot,” and she has the “courage to stand for right when it may not be popular to do so.” She ran, according to her biographer, “because it was the top job in her business, because it was the capstone to a lengthy and distinguished political career, because she loved the limelight, because she thought she could do a good job.” She lost every primary election but won 25 percent of the vote in Illinois. Among the Republican candidates at the time, in addition to Goldwater, were Governor Nelson Rockefeller of New York, Senator Hiram Fong of Hawaii, Governor William Scranton of Pennsylvania, Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. of Massachusetts, and Harold Stassen of Minnesota. In San Francisco, at the convention, 16 delegates were pledged to her. On the last ballot, she came in second to Goldwater with 27 votes, and she denied unanimous consent for Goldwater by refusing to withdraw her name, citing his extremism. Despite Smith’s ambition and many accomplishments, she was no feminist; her generation believed women should enter politics to reform it with their inherent moral superiority. After Smith’s failed attempt, it did not take long for another woman to aim for the presidency, a surprising one—an African American woman from New York City. |

|||||

Margaret Chase Smith arrives, waving from her car, at the 1964 Republican Convention in San Francisco. |

|||||

|

|||||

Shirley Chisholm |

Shirley Chisholm In 1972, as President Richard Nixon, a Republican, was preparing to run for his second term, the Democrats were in disarray. Scandal plagued Senator Ted Kennedy, and Senator Edmund Muskie of Maine shed tears of frustration in public. That boosted Senator George McGovern of South Dakota into first place, while former vice president Hubert H. Humphrey struggled to make a comeback. Then the first African American woman elected to Congress in 1968 threw her hat into the ring—becoming the first woman and first African American to run for the Democratic Party's presidential nomination. Born in Brooklyn in 1924 to parents from the Caribbean, Shirley Chisholm had lived in Barbados with her grandparents as a child and credited her grandmother with encouraging her self-esteem. Chisholm returned to New York to attend college and earned a master's degree in education, which qualified her to run a daycare center. When she became a state legislator and member of Congress from New York's 12th Congressional District, she only hired female staff. In Congress, she expanded the food stamp program and worked with Congresswoman Bella Abzug to pass a bill to fund childcare services—only to have President Nixon veto it. |

||||

The road to Chisholm's presidential run was a rocky one. Only on the ballot in 14 states, she was denied participation in a New York primary debate, whereupon she threatened legal action and was finally given a half hour to speak. With Gloria Steinem, she founded the National Women's Political Caucus to support female activists. And she was nominated for president by the National Feminist Party. But when African American men talked of a black political party, she urged them to not "give up on the system," saying, "we have made improvements." That year, 38 percent of delegates to the national Democratic convention were women seeking to influence the platform with a pledge for reproductive freedom and a vote for Chisholm. On the first ballot, Chisholm received 151 roll call votes, landing her in fourth place. She frankly admitted being "tired of tokenism and look how far we've come-ism," stating bluntly, "I met more discrimination as a woman than for being black. Men are men." Later, looking back at 1972, she wrote, "I ran because somebody had to do it first. In this country everybody is supposed to be able to run for President, but that's never been really true. I ran because most people think the country is not ready for a black candidate, not ready for a woman candidate. Someday..." Shirley Chisholm wore white in her campaign for the presidency, just as Hillary Clinton did this year. White was the chosen color of the suffragists in the campaign for the vote. It symbolizes purity. |

|||||

| Cyndy Bittinger, writer and historian, teaches Vermont history and women’s history at the Community College of Vermont. Her books include Grace Coolidge: Sudden Star and Vermont Women, Native Americans and African Americans: Out of the Shadows of History. Bittinger, a Vermont Public Radio commentator, wrote and presented several pieces on this subject for VPR this campaign season.

|

|||||