| Women's Rights — Where Do We Go from Here? | |||

| Cary Brown | |||

|

|||

Who hasn’t looked back on their past and thought about how things might have gone if they only knew then what they know now? It’s a question that inevitably leads to other, tougher questions. Have I come as far as I thought I would? What about my entire generation? What have we done to make the world a better place than it was when we arrived? In my high school yearbook, I stated my ambition: “To reform the world.” I wanted to fix things, to make things the way they were supposed to be, because I was so sure that things should be fair, equitable, peaceful, smart, and compassionate. I was a teenager and came of age in the ’80s—right around the time Vermont Woman newspaper was born. As a teenager, many things enraged me. My sense of justice (and injustice) was highly personal, but I could also see how it extended beyond the individual and into the social. I had many thoughts and opinions about how the world needed to be reformed. At some point in my childhood I realized that the default human being was, in everyone’s view, apparently male—females were extra add-ons, not the regular kind of person but some variant. This fed a swiftly growing sense of outrage and injustice that fueled my interest in politics and my engagement in social justice. Not to mention my engagement in hours of heated debates with boys in my high school classes. (Another peek into my senior yearbook: I was awarded “class arguer.”) It wasn’t just the belief that men were the default that enraged me. It was, much more, the result of that. Men seemed to have so much more power than women, so much more control over everything. It seemed as though the whole world was built around this idea that men deserved the power and women didn’t. As a teenager, I took it pretty personally. It was personal—because it was my life and my body and those of my friends’ that were at stake. Rape was a real threat, and it was terrifying. Sexual harassment was a fact of life—literally every girl I knew had been catcalled, groped, or taunted about her body many, many times. It was infuriating, but there didn’t seem to be anything we could do about it. The possibility of an unintended pregnancy was definitely very real and certainly happened all the time. Many of my friends had abortions, and plenty of girls in my school had babies. In my rural community, birth control was challenging to access. As I’ve gotten older, it’s all gotten less personal and more social, but interestingly, the themes that inspired my rage and indignation back then are still with me today. I have two sons and a much clearer understanding of the ways that injustice affects them in startingly similar ways. A system that grants power to some and denies it to others is unhealthy for all involved, and that is much easier for me to see now than when I was poking my head up above it back in the ’80s. A few decades later, I find myself in the unbelievably fortunate position to be able to put my passion to work professionally. And the things that pull at me are surprisingly similar now, even though the shapes have shifted somewhat. Freedom from sexual harassment and assault, access to reproductive health care, and economic equity and security for all women are powerful motivators and apparently not just for me—Vermont leads the country in many ways in all these areas. So where are we now? Where do we still need to go? What would my teenage self in the ’80s think if she could see what we’re up to in the 21st century? |

|||

|

|||

|

The ’80s were a dynamic time for women and employers, clarifying just what was and wasn’t OK at work. The fight against rape and assault that women had been waging in the ’60s and ’70s expanded to include unwanted comments, touching, and demands for sexual favors on the job. Women stopped being as willing to suffer in silence. The term sexual harassment was coined in 1975 at Cornell University, when a former employee filed a claim for unemployment benefits after she resigned from her job because of her supervisor’s inappropriate touching. Cornell denied her claim, saying she’d quit for “personal reasons,” and women on campus banded together to speak out and create awareness of the issue, bringing it national attention. The Cornell Human Affairs program distributed a questionnaire to a variety of audiences of women and found that 70 percent of them had experienced sexual harassment. A Redbook survey the following year, 1976, found that 80 percent of respondents had dealt with it. The director of the women’s section of the human affairs program at Cornell testified to the New York City Commission on Human Rights that in the past women had been reluctant to discuss it, noting “the ridicule and condescension” they experienced when they did. She went on to say, “Most male superiors treat it as a joke. At best, it’s ‘not serious’… Even more frightening, the woman who speaks out against her tormentors runs the risk of suddenly being seen as a crazy, a weirdo, or, even worse, a loose woman.” When Phyllis Schlafly testified to a Senate committee in 1981, she invoked the “loose woman” stereotype, saying that “sexual harassment on the job is not a problem for virtuous women.” The committee was charged with reviewing guidelines put in place by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission that would hold employers responsible for its workers engaging in sexual harassment—guidelines that committee chair Senator Orrin Hatch worried might be too inclusive, create too much antagonism toward women, put too much of a burden on employers, and “have the potential for infringing on freedom of expression.” By the time the ’90s rolled around, with Anita Hill testifying to the harassment she’d experienced working for Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas, things were starting to come to a boil, and the aftermath of her testimony (and ultimate failure, as Thomas was appointed to the Court) included a doubling of sexual harassment complaints nationwide and an increase in the payouts plaintiffs received in court. I think the optimistic among us hoped that Hill being disbelieved and disregarded was an anomaly and that the arc was bending toward much less sexual harassment. We may have been a little premature in that, as the last few years have shown us, with the #MeToo movement exploding in 2017. Instead of sexual harassment diminishing, it seems as robust as ever: a 2018 survey found that 81 percent of American women have faced it—a higher number than the Cornell survey of 1975! And history seemed to repeat itself in 2018 when another nominee for the Supreme Court, Brett Kavanaugh, found himself accused of sexual assault, and yet sailed through the nomination process. Accusers are still disbelieved and disregarded, as Dr. Christine Blasey Ford has found. The good news, however, is that #MeToo has not only helped make it acceptable to talk about harassment, it’s encouraged and rewarded it. And those in power are responding. In 2018, Vermont passed a law heralded as the strongest legislative response to #MeToo, protecting every worker from sexual harassment. This includes people working for the smallest employers, as well as those who aren’t necessarily typical employees, such as internsand independent contractors. The law also ensures that when Vermonters settle with the employers over complaints of sexual harassment, they can return to work, by forbidding provisions in settlements that ban someone from ever working for the employer again. |

|||

|

|||

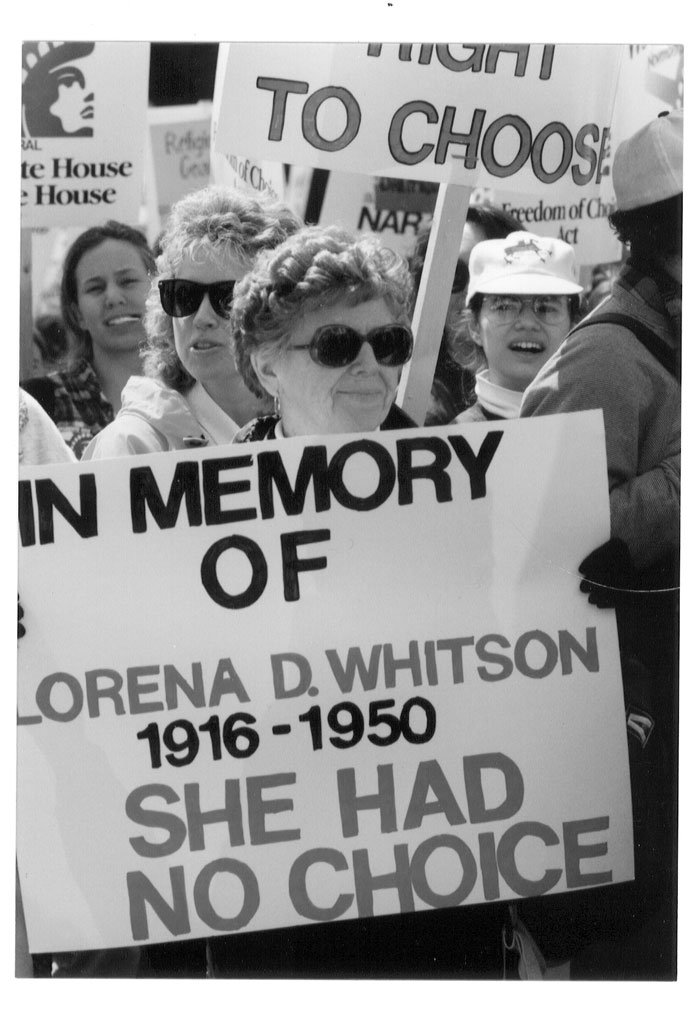

Vermont stands out in this national scene. In the Guttmacher Institute’s comprehensive review of state restrictions, Vermont is the only state with none at all listed. Additionally, Vermont is one of only 16 states that uses public money to fund all or most medically necessary abortions. Particularly notable is the law that Governor Phil Scott signed in June 2019. Vermont is now one of just two states (with Oregon) that explicitly protects the right to abortion and prevents restrictions. The legislature is considering going even further, with a constitutional amendment. If this passes (a process that will be years down the road), the Vermont Constitution will include Article 22 (personal reproductive liberty): That an individual’s right to personal reproductive autonomy is central to the liberty and dignity to determine one’s own life course and shall not be denied or infringed unless justified by a compelling State interest achieved by the least restrictive means. |

|||

|

|||

While the number of countries that don’t mandate paid parental leave can be counted on one hand (the United States taking one of those fingers), the number of US states creating such programs is rapidly growing. In 2013, the Vermont legislature created a Paid Family Leave Study Committee, recognizing that paid parental leaves keep women in the workforce longer and help reduce the gap in earnings. The committee recommended a comprehensive legislative proposal, which has been refined and amended multiple times in the years since but has not become law. Overall, we’re faced with a bit of a mixed bag in terms of progress for women, although I remain optimistic. In my decades of working for women’s rights in Vermont, I can’t say I’ve ever seen such widespread, dynamic, and committed energy being expressed for gender equity—and that’s a bar that keeps getting set higher and higher, I’m encouraged to note. I’m also encouraged by the growing understanding of the relationships among different kinds of oppression and bias, the acceptance of gender identity as fluid and inclusive, and the broad commitment to working for equity on all fronts, for all Vermonters. |

|||

|

|||

|

Cary Brown is the executive director of the Vermont Commission on Women.

|

||